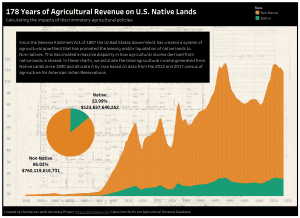

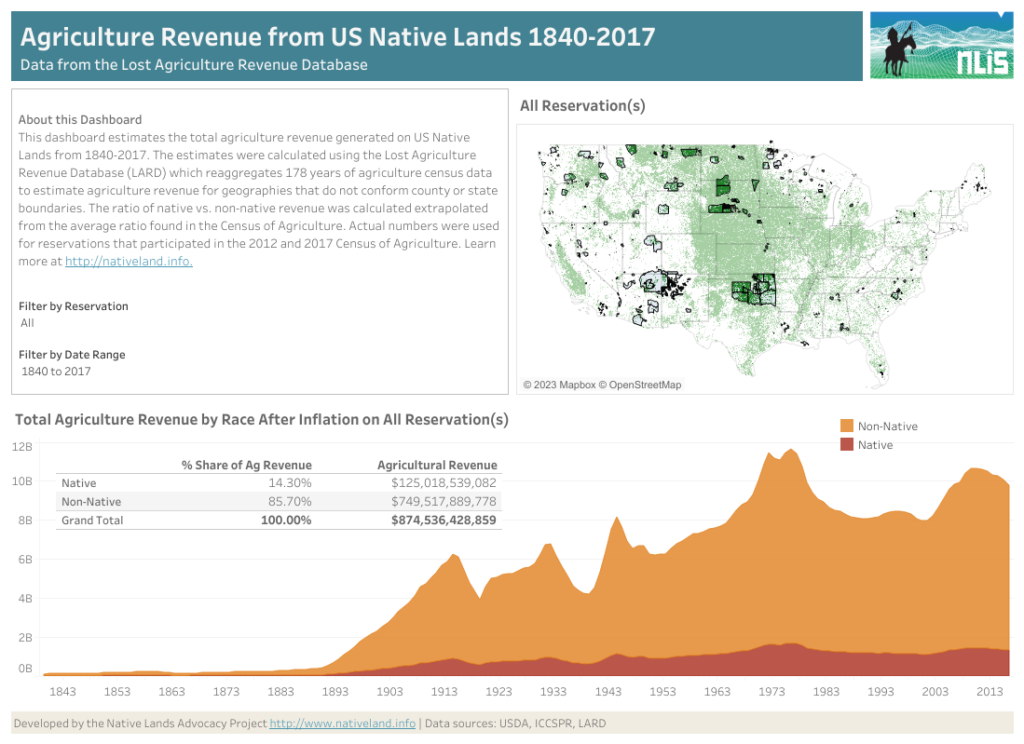

According to our Lost Agriculture Revenue Database, non-Native farmers have made $749,517,889,778 in agricultural revenue (85.7% of total revenue) on Native reservations since 1840, while Native farmers have made $125,018,539,082 (14.3% of total revenue). What factors contribute to this shocking disparity in agricultural revenue? And what do these numbers really represent for Native communities?

A Brief Overview of the L.A.R.D.

Three years ago, NLAP launched the Lost Agriculture Revenue Database (L.A.R.D.) to help quantify the impacts of land cessions and discriminatory agriculture policies of the United States government on Native communities. This database includes two dashboards that estimate, respectively, agricultural revenue extracted from all ceded lands and agricultural revenue received by Native vs. non-Native producers within reservation boundaries.

County-level USDA Census data makes it very difficult to understand what’s occurring on Native lands, which often overlap multiple counties (and sometimes multiple states). Using data from 1840 to the present, the L.A.R.D. disaggregates county-level census data into known agricultural lands of each county and then evenly distributes the census results (in this case, the sum market value of agricultural products sold). You can read more about the methodology involved in creating the L.A.R.D. here.

The name of the database is a double-entendre of the Lakota word "Wasi’chu," which translates as “takes the fat.” The Lakota use the word "Wasi’chu" to refer to white settlers, which is also used more generally to describe people with a greedy extractivist mentality; people who take instead of giving.

Agricultural Revenue from Ceded Native Lands

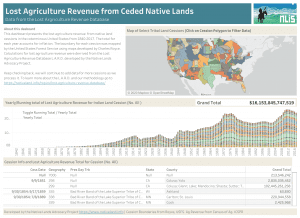

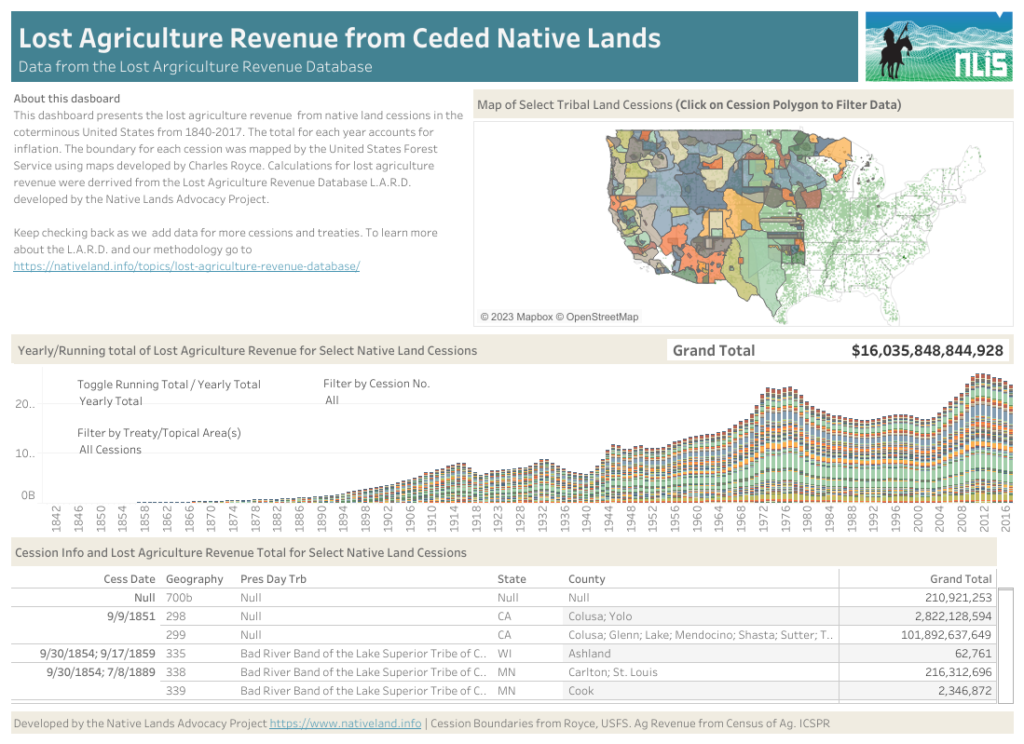

One of the dashboards NLAP developed for the L.A.R.D. is our Lost Agricultural Revenue from Ceded Native Lands. While this dashboard is not yet complete (NLAP is still adding cession boundaries), we currently calculate that farmers have generated $16,035,848,844,928 in agricultural revenue since 1840 from these ceded lands. This database can also be filtered for individual cessions, therefore allowing tribes to calculate lost agricultural revenue for just their own ceded lands.

While the calculations are approximate, this database nonetheless posits a concrete value for the financial gains settlers have enjoyed as a result of removing Native Nations from their lands. In many cases, the capital accumulated through these land cessions contributed directly to further settler expansion and development. Inversely, this database calculates the loss of economic potential for all Native Nations within their ceded lands.

However, we should not view these numbers just as dollar amounts. For Native communities, land has always represented much more than potential profit. Land is the Heart of All There Is; it connects people to all living things and in turn shapes peoples’ identity and how they inhabit the earth. Therefore, this database is a representation of how settlers have profited and continue to profit from disconnecting Native Nations from their homes and livelihoods.

Agricultural Revenue Disparities on Contemporary Native Lands

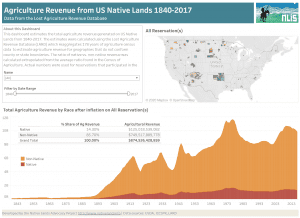

The other dashboard NLAP developed for the L.A.R.D. is our Agriculture Revenue from U.S. Native Lands 1840-2017. This dashboard calculates the differences in agricultural revenue made by Native and non-Native producers on contemporary reservations.

From our estimates, on all contemporary reservations, non-Native farmers have made $749,517,889,778 in agricultural revenue (85.7%) since 1840, while Native farmers have made $125,018,539,082 (14.3%). This dashboard can also be filtered to see the impact for each individual reservation.

These quantifiable disparities are a direct result of discriminatory agriculture policies, especially from allotment and leasing of prime agricultural lands to non-Natives. We have written in-depth about many of these destructive policies: the legacy of allotment and leasing of prime agricultural lands, non-Native control of Native lands, agricultural lending discrimination, and more.

However, again, we must emphasize that these dollar amounts are not mere numbers. This egregious disparity in agricultural revenue between Native and non-Native producers on Native lands is a quantifiable example of the U.S. government’s failure to honor the trust responsibility—a responsibility that the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld on multiple occasions, such as in the Cobell and Keepseagle class-action lawsuits. This mismanagement was also identified in the 1928 Meriam Report, which indicates that these issues have been well-known internally for at least the last century.

These numbers clearly show that Native communities are not the primary beneficiaries of their own lands. While this is not shocking news to Native communities (as many tribal communities and organizations have spoken out about the barriers faced in accessing and benefitting from their own lands), the L.A.R.D. estimates real dollar amounts that can be used for advocacy and education. It is our hope that the L.A.R.D. can be used to present a more accurate view of history so that better policies can be put in place which truly serve the interests of Native peoples.

Working to rectify the disparities identified by the L.A.R.D. does not only mean Native communities making more agricultural revenue on their own lands, but also having greater access to land and land data, greater autonomy over their food systems, and greater decision-making power over land use policies. In turn, these open more avenues for Native peoples to heal fractured relationships with their lands, non-human relatives, foods, medicines, and own bodies.

In other words, working to rectify these disparities means affirming and upholding Native sovereignty over their own lands and communities.

Written by Emma Scheerer