DATA SOVEREIGNTY

One of the main goals of the NLAP and the NLIS is to empower Native Lands through data and support Native efforts to build stronger sovereign research capacity. Because we are fully aware of the link between historical land oppression and data colonialism, we are committed to supporting the development of data sovereignty in Native lands.

Native Data Sovereignty: A Summary

“American Indian nations, like other nations, are decision-making entities that need reliable information about their citizens. However, existing data on tribal populations are often limited to those developed by others—usually federal, state and local governments”

(Rodriguez-Lonebear, 2016) Tweet

“tribes exercise Indigenous data sovereignty through the interrelated processes of decolonizing data and Indigenizing data governance; and data are the building blocks of good governance; however, equal access to these data is not guaranteed. Tribes may not have ready access to the data collected by external agents about their citizens, lands, and resources, which underscores the need for tribal protection, ownership and application of tribal data”

(National Congress of American Indians) Tweet

Table of Contents

Increasingly, what we know about the world is shaped and defined by data. Data shapes how we think, influences our behavior as individuals, shapes our social norms, and guides our policies and laws. Data can also be a powerful tool for surveillance and control and has been an integral part of European colonization around the world, especially for the unique brand of settler colonialism that took shape in North America. At its most basic, settler colonialism functions to replace Indigenous populations with an invasive permanent settler population. Historically, this has occurred through outright genocide, assimilation, and/or apartheid.

Sadly, all three of these settler colonial functions have been part of the colonization of North America, and, in large part, these policies were data-driven. That means that data was collected and used to monitor Indigenous populations and their lands and assess the efficacy of specific replacement policies employed. To this end, the United States Government has maintained meticulous records about Indigenous populations, their health, incomes, education, land status, law and order, etc. And, even though Native American Tribes are recognized as sovereign nations within the United States, the U.S. Government still maintains almost complete control over this data.

Additionally, Native communities have also been excluded from other datasets, collected by the U.S. Government, that could be utilized to strengthen their self-determination, enhance their access to and control over lands, advocate for their rights, and increase their political power (resisting replacement). There is other data that is still not being shared that could be used to create greater accountability and better assess the government’s performance in its current and historic self-appointed role as “Trustee” of Native lands. Gaining control over data about your people and lands is a crucial pivot around which Native Nations can organize truly sovereign land management. Still, this data must be weighed against the ways it can be used by adverse parties for nefarious purposes, such as the desecration of sacred sites, theft of sacred objects and human remains, land speculation, the unauthorized exploitation of natural resources, etc.

The Native Lands Advocacy Project promotes the right of tribes to control what data is collected on their lands and among their members, as well as who has access to that data. We also believe the Federal Government has a moral and fiduciary obligation to provide data to tribes, especially data that can be used to assess its performance as self-appointed Trustee. We also promote the right of tribes to assume any and all administrative responsibilities currently assumed by the federal government, and we believe the Federal Government has the moral and legal responsibility to provide training and resources to tribes to enable that. This includes the complete transfer of and ongoing collection and management of their own data and the right to “opt-out” of Government data collection, including data acquired through remote sensing. In support of these rights, we make it easy for tribes to “opt-out” from data on our site using this online form.

Documenting Data Colonialism in Native Land

Two colonial patterns intertwine to create secrecy and impede on the exercise of sovereign land management:

- The historical mismanagement of tribal land through the passing of acts that do not hold native interests in priority and in the contrary benefit non-Natives

- A pattern of concealing existing land data or not collecting it altogether

To this day, much of the data about Native lands and Native peoples is collected and maintained by the United States Government. In 1824, the US Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) was appointed by the US Congress to “enhance the quality of life, to promote economic opportunity, and to carry out the responsibility to protect and improve the trust assets of American Indians, Indian tribes and Alaska Natives.”

Despite this huge responsibility, there is very little transparency or accountability regarding the BIA’s performance as Trustee. In fact, it has long established precedence in the deep mismanagement and concealment of data in direct opposition to its own stated role. In 1928, the Meriam Report was already clearly denouncing mismanagement practices occurring as part of the BIA’s involvement on Native land, supported by the deliberate act of data concealment or misreporting.

The most recent report led by the Department of Interior’s Office, the 2009 Program Evaluation of the BIA Realty and Trust Program, acknowledged that: “The BIA Realty and Trust Program plays a key role in keeping the DOI promise “to protect and improve the trust assets of American Indians, Indian tribes, and Alaska Natives.” yet he excoriated the Bureau for its continued failure to develop meaningful performance measures. Specifically, the report states that in “Real Estate Services, acquisition and disposal of land and lease compliance activities are significant functions that also lack measures.” In brief, even federal institutions recognize their role in providing inadequate data for Native land, although no measure is effectively taken to remediate this pattern. The failure of the BIA to provide even basic information about leasing and transactions of Native lands makes public scrutiny of these programs difficult, if not impossible.

Towards Native Data Sovereignty

Ultimately, Indigenous-led research must be at the forefront of producing knowledge for Native land and beyond. According to Tuhiwai Smith (2014), “Indigenous research seeks to recover a peoples’ path to well-being, to find the new/old solutions that restore Indigenous being in the world. The impacts are part of an intergenerational long game of decolonization, societal transformation, healing and reconciliation, and the recovery of a world where all is well”. However, we have shown how the lack of access to relevant and appropriate data seriously undermines Indigenous research capacity.

“For every act of oppression, there is an act of resistance”

(Stephen Small) Tweet

This quote reminds us that the path to Indigenous data sovereignty is not developing in a vacuum; it is the manifestation of an ongoing struggle for asserting existence and negotiating boundaries since the time of first contact.

Indigenous data sovereignty debates have increasingly developed across the land. They establish guidelines suggesting regulations for data collection, data management (Kukutai & Taylor, 2016; Schultz & Rainie, 2014) and how to handle the relationship between Native vs. non-Native science and knowledge (Chino & Debruyn, 2006; Maldonado et al., 2016; Moller, Berkes, Lyver, & Kislalioglu, 2004; Mutua & Swadener, 2004; Tuck, McKenzie, & McCoy, 2014; Tuhiwai Smith, 1999).

While the goal remains to support the full development and use of data that reflects Native peoples’ worldviews in their diversity and depth, the oppression still occurring on Native land as a byproduct of the lack of translated data collected and used by non-Natives calls for translation models. In other words, colonized datasets also need to be accessible to native peoples so they can act and stop the land oppression that results from their use. An excellent example can be found in how it is extremely easy for extractive fossil fuel industries to access the same native land tenure data that Native peoples struggle to obtain from responsible federal entities.

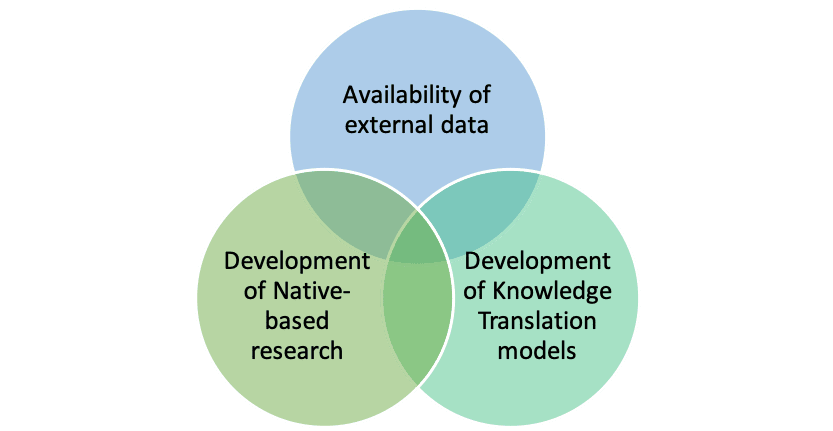

Ultimately, we could summarize the path forward toward data sovereignty as a triadic movement between 3 complementary goals:

1) Make external data accessible

2) Develop native-based research

3) Develop knowledge translation models (see figure below).

Availability of External Data

Holding Institutions Accountable

Because the sovereignty of Native Nations is compromised by their trust relationship with the United States Government, the United Government must be held accountable for its performance as Trustee. To begin, we believe accountability must include access to the data required to assess its performance. At its most basic, this must include regular access to data about the status of Native lands, land appraisals and transactions, data on leases of Native lands and resources held in trust by the federal government, rights-of-ways granted on Native lands, data on the Individual Indian Money (IIM) accounts managed by the federal government, data on loans and loan guarantees made by the federal government that encumber Native lands and assets, and data needed by tribes to assess the current and historical impacts of federal policies on Native Americans.

We are encouraged by the recently passed 2019 Open Data Act, which proclaims that: “agencies will be called upon to maintain comprehensive data catalogs and designate a nonpolitical chief data officer. The White House Office of Management and Budget will also create a Chief Data Officer Council, comprised of chief data officers from across the government, to ‘establish Government-wide best practices for the use, protection, dissemination, and generation of data.’”

However, we believe a dialogue needs to occur between tribes, individual Native Americans, Native-run organizations, and the government to identify a specific set of performance measures and the data that shall be regularly published by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In addition, we believe the U.S. Government, out of recognition for the damages caused by centuries of data colonialism, should allocate the resources and person-power needed to compile data where needed and reconstruct the historical data on the abovementioned topics.

Lastly, we believe the U.S. Government has prevented the dissemination of data it collects (in whole or in part) about Native Americans and their lands. We believe this has been done either to hide malfeasance or through a misguided sense of paternalism (i.e. to “protect” tribes from predatory corporations or other third parties) or a combination of both. We believe this “protection” has done more harm than good by hiding the reality about Native Americans and their lands. Powerful entities already have access to this data, whereas the entities that need it most, tribes and Native people, do not. In fact, the government relies on many for-profit contractors, like IHS Markit, to maintain and query their data. These companies are also in the business of providing data to private entities like oil, gas, and mineral interests information regarding land ownership, right of ways, land valuations, land cover, soils, etc. That is why we feel it is important that government data, as long as it does not violate the Privacy Act of 1974, be made available to the people who need it most and to the public so it can be utilized, scrutinized, and debated by the various stakeholders including researchers, journalists and the public at-large.

Publishing Existing Data

The NLAP has demonstrated that, while not easy, it is possible to overcome external data obstacles by utilizing modern GIS technology and archival research. Extended research efforts are required to sort, process, and analyze existing data into usable units.

However, in the meantime, we need to push our legislators to enforce existing laws and develop new legislation to mandate the aggregation of data for Native American lands into meaningful units, both local (as is the case for GSSURGO and CDL) and national (as is the case for tribal land classification and leasing data). With additional time, we think that FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) could become the third pillar of this approach.

Developing Native-Based Research

The second goal is for tribes to continue fostering their own research capacity-building and agenda. This highlights three main questions for Native communities to answer:

- What does our Native knowledge look like?

- How can we collect knowledge in traditional ways?

- How can it be translated and shared with other knowledge systems?

Native Ways of Knowing

The lack of data sovereignty on Native land (Kukutai & Taylor, 2016) is nested in colonial power dynamics that result in epistemicide (De Sousa Santos, 2014; Grosfoguel, 2017) or the suppression of knowledge systems other than Western-based science. Knowledge from Indigenous cultural frameworks often remains unheard of due to several processes:

- Absence of formats recognized as legitimate forms of knowledge: much traditional knowledge used to be passed on informally and through oral storytelling

- Use of methods and analysis types that downplay Native understandings and the validity of their claims

- Absence of most basic data to sustain land and food claims

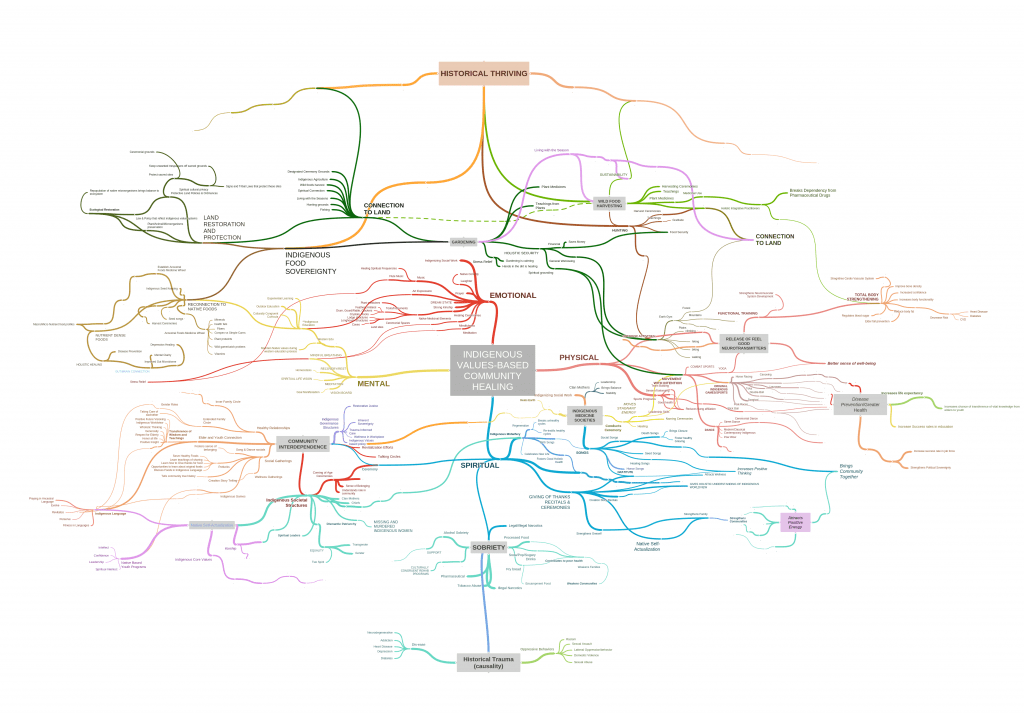

Native knowledge is not a single form of knowing. It is characterized by a myriad of ways to understand the world. Knowledge is place-based and anchored in the land, which emphasizes the damage caused by external data collection methods. General patterns show that Native knowledge is hardly described in linear ways and tends to interconnect dimensions that are often ignored by mainstream Western science models. Additionally, Indigenous knowledge is often narrated orally and in very visual terms. This makes visualizations a powerful tool to articulate Native ways of knowing. In the example below, Native wellbeing specialist Thosh Collins attempted to represent what “Native wellbeing looks like.”

Native Ways of Collecting Data

“Information, data, and research about our peoples—collected about us, with us, or by us—belong to us and must be cared for by us.” (US Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network)

Due to its colonial history, collecting data in Indian country is a particularly sensitive topic. Evaluating local systems comes with “many unknowns” (First Nations Development Institute & Balbas, 2006), and determining what the right data looks like can prove very complex. However, Rodriguez-Lonebear reminds us that: “Our people have always been data gatherers.” Rodriguez-Lonebear refers to the ancestral capacity of Native communities to maintain and transmit culture through traditional knowledge systems. These are a testimony of possible venues for designing local data systems. Local communities should strive to 1) create their own indicators, 2) set their own benchmarks, and 3) organize their own data storage. But such systems can look very different from one Native community to another. While data holds strategic power that can help Native Nations implement a vision to inform decisions, know their assets, track performance, and defend their rights, data can be collected and handled in multiple ways that suit a community’s particular vision (Schultz et al., 2014).

In Indigenous literature, community assessments are advocated as critical tools to provide native people with the missing data they need to increase self-determination and autonomy. The now popular Food Sovereignty Assessment Tool, first created by the First Nations Development Institute in 2004, has been modified and put into practice by an increasing number of food initiatives (Bell-Sheeter, 2004). It includes survey and workshop templates to conduct a thorough food assessment that considers Native worldviews, cultural meaning of food, relationship to the land, and governance. This tool was described during a Food Sovereignty summit as: “a valuable empowerment tool that can best be used by disseminating the assessment to many communities, gathering data, compiling the results, and creating a map of Indigenous Peoples food resources and activities, both at the local level and for use in developing a national Indigenous Peoples food resource map” (First Nations Development Institute & Balbas, 2006).

A striking example is also given by the Diné Food Sovereignty initiative (Woods, 2014). There, the Diné Policy Institute created a comprehensive survey-based assessment of the local food system investigating its meaning and process. Mapping answers to questions such as “Who is currently working to solve food problems in your community?” allows one to draw a picture of the state of local food (Woods, 2014). The same assessment model served as a baseline to create the Native Food Sovereignty Alliance, where strengths and weaknesses of food sovereignty implementation were analyzed (First Nations Development Institute & Balbas, 2006).

With the rise of social media and the increasing access to data and knowledge-sharing platforms, there has been a resurgence of interest for Native peoples, particularly youth, to relearn Indigenous knowledge. The common feeling of unworthiness that accompanied the dismissal of Indigenous knowledge and knowers tended to mutter people’s voices further. By contrast, the instant networking of Indigenous environmental alliances, demonstrated in recent struggles like Standing Rock, enabled people to break geographical isolations and feel empowered to speak. This further emboldened the organization of Indigenous sharing platforms and renewed the hope that learning and sharing could actually impact local communities’ lives for the better. There is a new momentum for tribal members to self-organize their knowledge systems, and the role of data is crucial in this process.

Developing Translation Models

Much harm was caused to Native lands due to translation issues. For this reason, many Native researchers consider knowledge translation essential to establishing dialectic understanding between Western science and Indigenous knowledge. This can ensure the transparency of data and data-driven decisions and make Native knowledge understandable and visible to the rest of the world. Indigenous ways of knowing are currently attempting to gain a voice in a field where they have been systematically silenced. (Cajete (Tewa), 2005; Johnson et al., 2015; Kealiikanakaoleohaililani & Giardina, 2016; Kovach, 2010; Nakata, Nakata, Keech, & Bolt, 2012; Querejazu, 2016; Whyte, Brewer, & Johnson, 2016).

On the one hand, translating knowledge without altering meaning is key to fostering the understanding and incorporation of Indigenous knowledge into decision-making. On the other hand, Native scholars and practitioners are starting to perceive how using Western epistemologies and tools while holding on to cultural identity can enhance community empowerment by leveling the fields of social justice and calling on the acknowledgment, reparation, or remediation of harm systematically done to their communities. This takes knowledge and the mastering of data analysis to present compelling stories to decision-makers. This is why many capacity-building-oriented projects are currently happening in Indian Country.

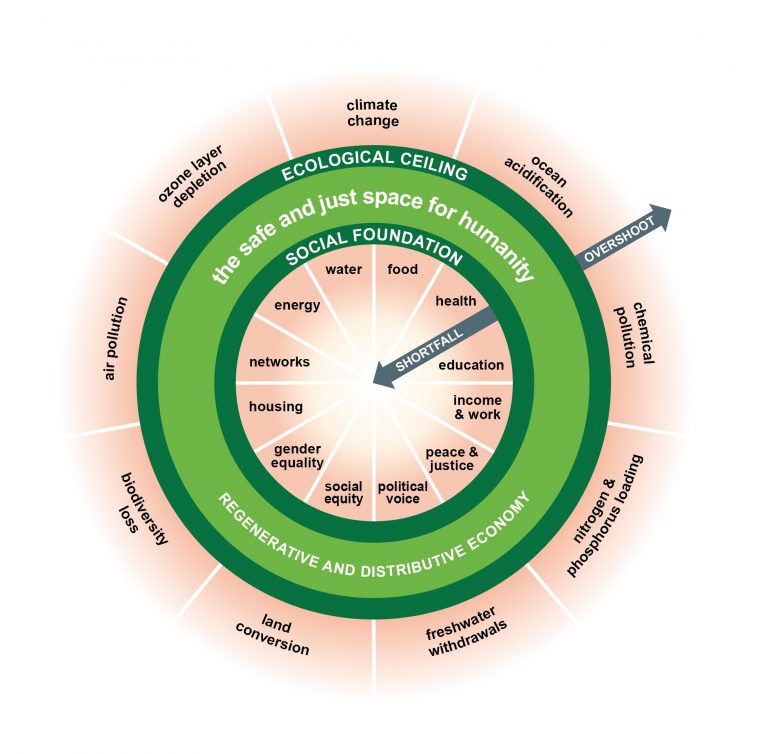

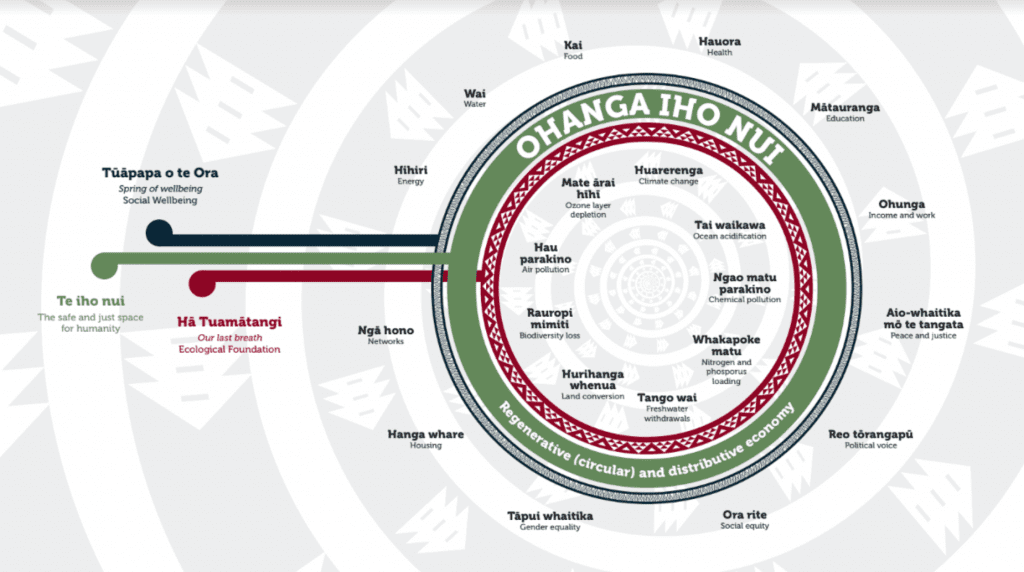

Although it does not concern US-specific Native knowledge, a recent example of successful knowledge translation is found in the alteration of Kate Raworth’s famous Doughnut Economics diagram into the New Zealand Indigenous Te Reo Maori model (see below). While Raworth’s model has been globally acclaimed for its capacity to render the complex balance between the earth’s ecosystem and the social world from a Western progressive circular economic thinking, Indigenous woman researcher Teina Boasa-Dean pointed out how the Maori understanding of the model would differ. While their first version included Maori-translated terms, she and three other women researchers realized that the whole model had to be reversed to represent the Maori views, as the ecological ceiling had to be placed at the center. Comparing these two models is a good example of the contribution of visual translation models to Indigenous data sovereignty.

Commitment of the NLIS

Through innovative methodology and data collection, the NLIS website actively participates in challenging data colonialism. While we recognize the limitations of currently available data processed by the NLIS, we aim for this tool to create a momentum around Native land data and data sovereignty.

Our Commitment

- To approach our work with a good heart by always doing our best to honor Indigenous peoples and Indigenous ways of knowing

- To critically and carefully weigh the value of a particular data set for promoting Native peoples vs. how that data might compromise a community’s privacy and right to opacity.

- To support Native research capacity-building

- To license our data products using the Creative Commons “CC BY-NC-SA 4.0” so they can be shared but not be used for commercial purposes.

- To practice a forward-thinking methodology geared towards constantly improving datasets

- To participate in changing the perception of Native land through data