Last summer, the Native Lands Advocacy Project developed a Historic Loss Assessment—articulating lost lives, lands, and resources for the Native Nations of Colorado—for the Truth, Restoration, and Education Commission (TREC) of the People of the Sacred Land. The findings of the TREC can be viewed here in three comprehensive reports.

NLAP was honored to be part of this work, and in the process of developing the Historic Loss Assessment, our team came to realize the power these tools have for correcting historically harmful narratives and advocating for true and equitable pathways forward. This series of blog posts (start here) outlines some of the processes and data tools NLAP developed to complete this assessment. This series is not a comprehensive review of the final TREC assessment; rather, through these posts, we aim to promote the usefulness of such a tool so that these assessments may be completed in more states.

Disclaimer: In sharing these processes, it is NLAP’s understanding that they will be used by, and for the benefit of, Native peoples. While we always encourage non-Native individuals and scholars to learn Indigenous history, the creation of a Historic Loss Assessment must be driven by the relevant Indigenous communities. Therefore, any place this post references “consulting” Native voices, this refers to an organization facilitating conversations between involved tribal parties and/or tribal groups consulting with one another—not non-Native researchers reaching out to tribal groups for their histories and data.

This blog post covers the first four sections of a Historic Loss Assessment, all having to do with Native lands:

Land is not mere property to Native communities, and there is no way to truly quantify the pain and intergenerational trauma caused by land dispossession and relocation. But by design, a Historic Loss Assessment primarily focuses on quantitative impacts out of a recognition that, in Western ways of knowing, numbers have power. By calculating these totals, this report seeks to not only identify what has been taken from Native peoples but also how this theft became the original source of capital that built Colorado and the West.

An Indigenous History of Your State

Sue Kennedy. Fall at Lindenmeier Arroyo, Photograph, History Colorado, Sept. 25, 2014.

Unfortunately, accounts of Native peoples in the present-day United States often begin with European contact. This creates the misconception that Native groups were static and had little meaningful impact on their lands before Europeans arrived. In reality, Native societies have always had complex relationships internally, with other tribal groups, and with their lands and non-human relatives.

The Historic Loss Assessment for Colorado began with a brief overview of the Indigenous history of the present-day state to situate the following data in its proper context. Native Nations know their own histories best and therefore should be the primary voices in creating this section.

Locations like the Lindenmeier Site in Colorado (pictured on the left) confirm tribal testimonies that Indigenous peoples have lived on Turtle Island since time immemorial.

Traditional ancestral knowledge and stories tell of a steadfast Indigenous presence on Turtle Island since time immemorial. In addition to this prior knowledge, modern-day archeological observations confirm the long-lasting presence of Indigenous communities in what is now known as the state of Colorado.

Land History

In the land history section of the Historic Loss Assessment for Colorado’s Native Nations, the TREC documents the major periods when European powers and later, the United States, extended dominion over the lands which would eventually become Colorado. This included different European land purchases (such as the Louisiana Purchase), land cessions through treaties (using digitized Royce Cession boundaries for visuals), and land cessions through Acts of Congress (after the passing of the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act, which ended formal treaty-making). Mapping these land claims provides a powerful visual representation of European expansion into Native lands. See the video of European land purchases on the right.

Land purchase/treaty visuals developed by NLAP for the TREC. These images can be found on pages 9-15 of the final assessment.

U.S. Treaty/Cession visuals developed by NLAP for the TREC. These images can be found on pages 13-22 of the final assessment. Visuals are especially important, as maps can visualize the chronological progression of settler forays into Native lands.

It is important to understand how these land claims actually functioned. There is a common misconception that one European power purchasing land from another was a transfer of ownership. However, in reality, land purchases between European powers transferred the “right” to make treaties; until land was ceded by Native Nations, it did not “belong” to any European power. For a helpful explanation of the process of land dispossession, see Lakota legal scholar Mario Gonzalez’ interview here.

It’s also necessary to acknowledge the complicated nature of treaty history. The existing power imbalances between the United States and individual tribes make treaty history inherently fraught. In many cases, treaties were negotiated under conditions of dishonesty, bribery, coercion, and/or the threat of violence. It is important to consult individual tribal voices about the treaties to which they were party.

Loss of land can be calculated by subtracting acres of unceded land in the state from the state’s total acreage. In Colorado, the TREC calculated the loss of land via cessions to be 65,535,478 acres. Below, we’ll explain more in-depth ways of quantifying the dispossession of Native lands.

In Colorado, Native Nations lost 65,535,478 acres to land cessions via treaties.

Land Dispossession

All land ownership claims in the United States can be traced back to land patents or similar documents, and the U.S. judicial system currently holds land patents as the supreme title to a particular land area. The Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office (GLO) database allows users to explore original land patents, including Homestead, Morrill Act, Timber, Sale-Cash, Military, and hundreds of other entry classes.

The purpose of examining these historical land patents is to demonstrate their instrumentality in removing Native peoples from their homelands. The dominant types of entry classes reveal settler motivations in claiming Native lands, and the signature date on each patent shows when individuals were making claims to those lands. In Colorado, there are thousands of acres of land that were patented before treaties were ever signed—in other words, thousands of acres of land that were illegally claimed by settlers.

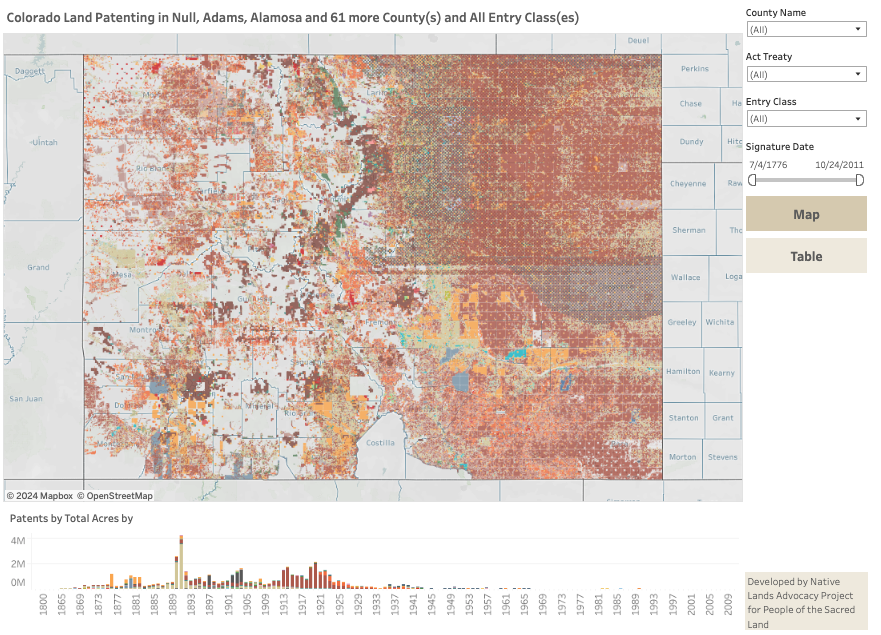

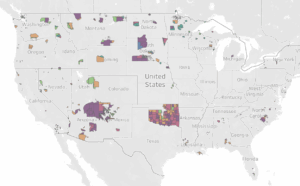

NLAP contracted Native scholar Joshua Meisel to map and animate the GLO data for the state of Colorado using a process described in this article, resulting in the creation of a GIS-based vector boundary dataset of land patents. This dataset is an interactive dashboard which can be filtered by county, patent entry class, land treaty, and date. This dashboard quantifies both the number of patents in each entry class and the total acreage within each entry class. In other words, the dashboard powerfully visualizes land dispossession in Colorado. While the dataset and dashboard were originally completed for the state of Colorado, they can be replicated for other states.

See the interactive dashboard in the two videos below. The video on the left is a timelapse that maps all entry classes of Colorado patents. The video on the right is also a timelapse, but instead of a map, it shows a chart of the entry classes over time. Both of these visuals were developed by NLAP for the TREC & can be found in pages 20-42 of the final assessment.

As demonstrated by the video on the right, the top ten patent entry classes in Colorado were:

- Homestead Act: 21,835,708 acres

- Sale-Cash Entry: 14,241,992 acres

- Colorado Enabling Act: 4,391,374 acres

- Homestead Stock Raising: 4,187,932 acres

- Union & Central Railroad: 3,818,105 acres

- Private Land Claim: 1,380,556 acres

- Timber Culture: 1,126,396 acres

- Desert Land Act: 821,223 acres

- Acquired Bankhead Jones: 678,082 acres

- General Land Exchange Act: 601,164 acres

The Homestead Act alone accounts for over 21,835,708 acres of dispossessed Native lands in Colorado.

Value of Dispossessed Lands

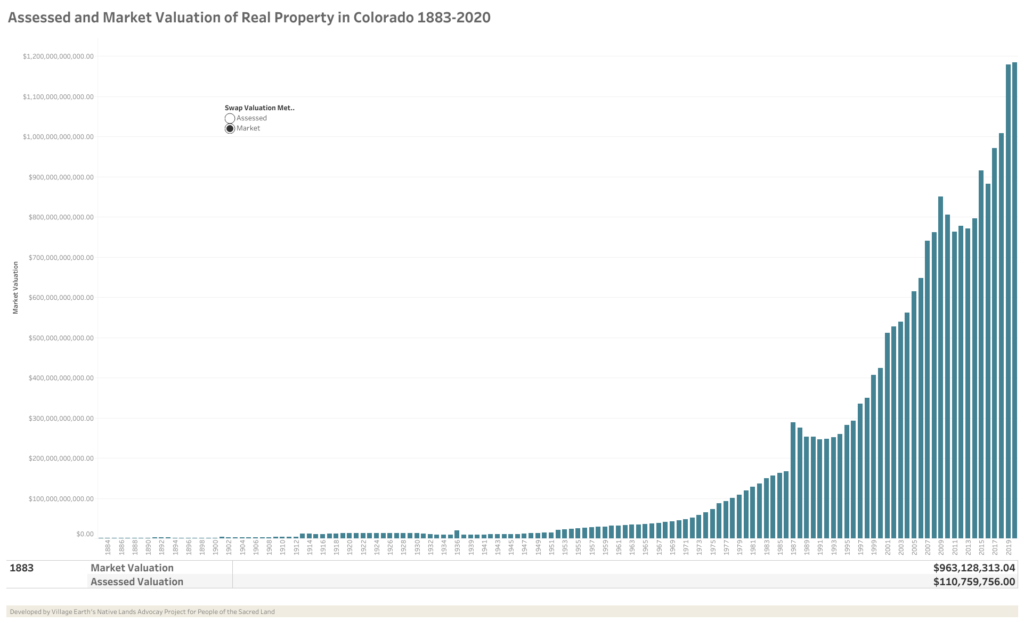

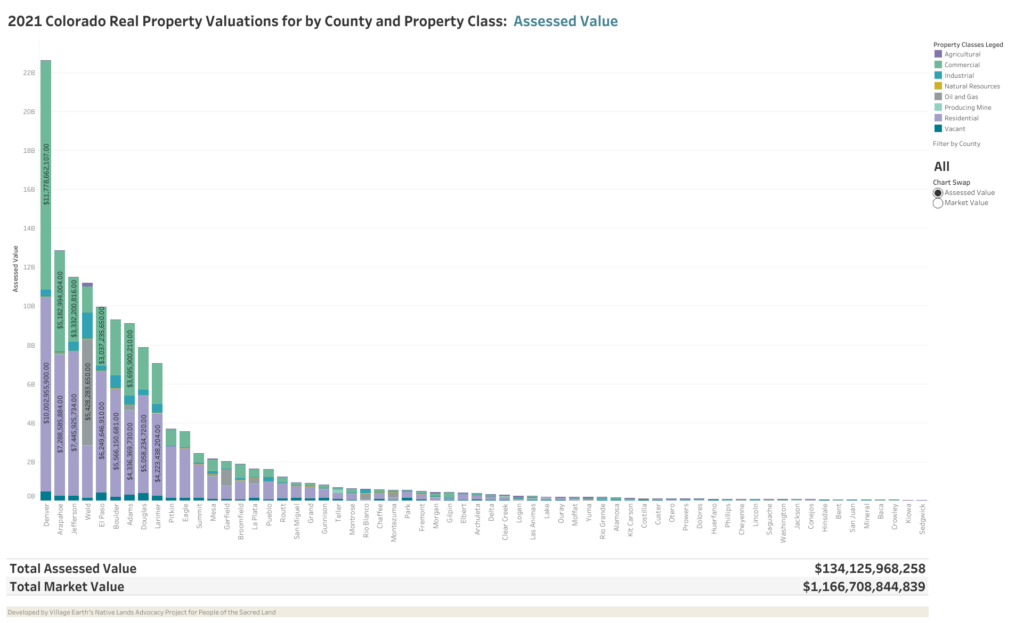

Using the total acres of patented land in Colorado (calculated above), NLAP calculated the dollar value of dispossessed Native lands. These calculations were for both market and assessed value, for the value of the land at the time it was taken (cession dates) and for value in the present day. The dashboards below, developed by NLAP for the TREC, can be viewed on pages 41-18 of the Historic Loss Assessment.

The 2021 estimated market value of these lands is $1,166,708,844,839. The estimated market value of these lands at their time of cession is $6,857,720,735. These calculations were state-specific and complex enough that a brief summary here is not sufficient to explain them. If you have questions about calculating the value of dispossessed lands, please contact us at info@nativeland.info.

Native nations in Colorado were dispossessed of an estimated $1.17 trillion worth of land.

We must again emphasize that land has always represented much more than a dollar value to Indigenous communities. These calculations are not intended to minimize the deep relational ties Native peoples have always had to their lands, but instead to help quantify how land dispossession was an immense theft.

This blog post is part of a series that documents our processes in creating a Historic Loss Assessment for the Truth, Restoration, and Education Commission (TREC) of the People of the Sacred Land. To view the landing page for the rest of the series, click here.

Written by Emma Scheerer