By Aude K. Chesnais

Introduction: Lending and Debt on US Native Land

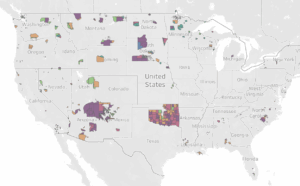

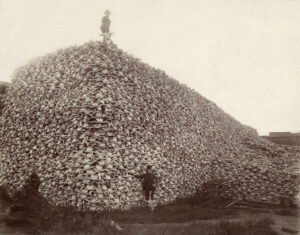

In 2018, the Keepseagle settlement shed light on widespread lending discrimination across the native agricultural landscape. Native Americans sued the US Department of Agriculture in an attempt to settle historical lending discrimination, which resulted in a 720 million dollar settlement, split between individual payouts to native producers and funding for agricultural research and outreach. Racial disparity remains huge in native agriculture, as confirmed by recent analyses from the Native Lands Advocacy (NLAP) project. In a recent dashboard exploring the distribution of agricultural revenue across race, we showed that 90% of the agricultural revenue on US Native Land is captured by non-native producers, while the majority of producers are Native. But how much does access to lending really impact agricultural revenue on native land? More data from the USDA 2017 Census of Agriculture for American Indian Reservations can help us find out.

Firstly, looking at Debt interests payments by reservation and race of producers provides an estimate of the distribution of farm debt for tribal geographies, and can help explain the racial disparity in agriculture on US Native Land. While data on access to loans is extremely hard to find at this geography level, a category called “Interests Paid on Debt”, described as “interest and finance charges paid in 2017 for debts secured by real estate and on debt not secured by real estate”, can be used as a proxy to estimate the breadth of lending, and the data allows for comparison across race of producers. In our newly released dashboard, we are showing that more than 82% farm debt is held by non-Native producers. This analysis controls for operation size because we aggregated the data at the reservation level, showing a similar pattern across the entire native agricultural landscape

Key Findings: Lending Highly Predicts Revenue on Farms

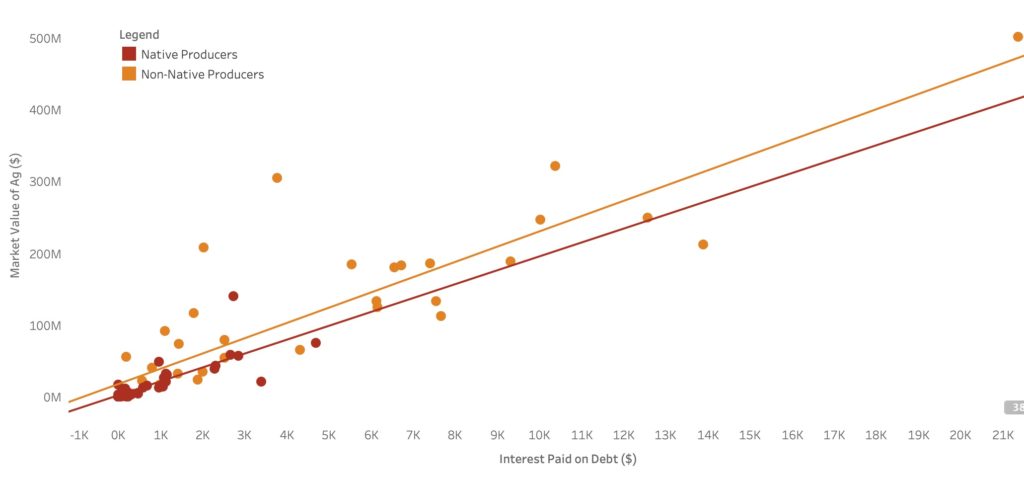

The story gets more revealing when comparing farm interests paid by race to agricultural revenue. To reveal this relationship, we plotted interests paid by producers to total agricultural revenue by reservation, and highlighted this relationship across producers’ race. The model shows that “Farm Interests Paid on Debt” explain about 83% of the variation of Agriculture Revenue. Results are amazingly consistent throughout reservations and across race, with two extremely significant respective R-Squared of 0.795 for non-native producers and 0.64 for native producers.

The strength of this relationship shows how important loans are to increase farming revenue for native farmers on native land, while in the meantime, the distribution of farm debt also confirmed how little native farmers have access to these loans. These findings highlight the need for policies to focus on increasing access to loans by native farmers in order to increase agricultural revenue. It will be extremely interesting to compare these findings with data on next census, to see, for instance, if claims such as the Keepseagle settlements had any impacts on discriminatory lending.

Now what?

This analysis allows to confirm important trends. Firstly, there is huge racial disparity in the distribution of farm lending across native land. Secondly, access to loans seems extremely important to increase the share of agricultural revenue by native producers on reservation, and redress the current disparity where 90% of the revenue is captured by non-native farmers and ranchers while the majority of producers are Native.

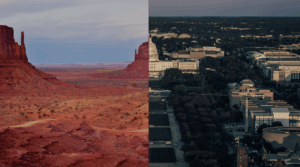

However, while this relationship shows the capacity of debt to produce more capital, it cannot serve to make inferences about the quality of local food-systems. Indeed, these models focus on commodified agriculture, and could be summarized bluntly as the capacity of investment (capital) to predict revenue (capital), in other terms a very western-centric view of agriculture, which contrasts with the richness and depth of native agriculture. These findings can, however, serve the struggle to redress the structural injustices still occurring on native land today, which impede on the sovereign use and management of agricultural resources on US native land.

In this broader struggle, discriminatory lending practices are just one piece of the picture. Liquidation of land to non-Natives, unfair leasing practices along with other series of historical measures that forcibly commodified native land are together responsible for the challenges faced by native producers today, which makes data analyses such as this one critical to measure the breadth of injustice and inform policies to support social justice and sovereignty on US native land.