Nestled in the hills, meadows, marshes, and forests, between the Ohio and Mississippi River systems and the Great Lakes, are the Universities of Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, and Kentucky, as well as Cornell University, Pennsylvania State University, West Virginia University, Purdue University, Michigan State University, and Ohio State University. These are all Land-Grant Universities or LGUs. Four of these LGUs—Purdue, Ohio, Illinois, and Kentucky—rank among the top ten of the original 52 Land-Grant Universities, for which the greatest amount of land from indigenous tribes, bands, and communities was ceded or seized.

Purdue University is pivotal to this region, as it’s positioned in the heart of an agricultural belt that stretches across the central latitudes of the United States. Purdue, like other Land-Grant Universities, formed immediately following the passage of the Morrill Act of 1862 (Hipp & Martin, 2018), for the purpose of educating generations of farmers, teaching technical trades, and later providing for agricultural and science research (Ahtone & Lee, 2020).

The decision to add military strategy to the offered fields of study tipped the scales in favor of the passage of the Morrill Act (Croft, 2019), which was a Civil War era act of Congress.

Signed by Abraham Lincoln on July 2, 1862, the legislation allowed for investment in LGUs and ongoing federal endowments to be accomplished through the expropriation and sale of Indigenous lands.

National Institute of Food and Agriculture. (2022). Land-Grant Colleges and Universities [Map]. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.nifa.usda.gov/land-grant-colleges-universities-map

These Land-Grant Universities were funded through the cession (by treaty, unratified treaty, or seizure without treaty) and subsequent sale of Native lands, which had far-reaching impacts on the 245 tribes and bands affected (Atone & Lee, 2020). The sale of 380,440 acres of Native lands from California to Michigan raised $212,149 to fund Purdue University alone. Land that was purchased from the Chippewa through the treaties of 1837 and 1842 cost the government 8¢ and 7¢ per acre respectively, while land taken by force was much more costly to the United States, so treaties were the preferred method of land acquisition (LaDuke, 2014).

According to stipulations of the Morrill Act, land with minerals was not to be sold for LGUs, which left forests, wetlands, and agricultural lands to bear the weight of transition away from indigenous stewardship. Much of the ceded or seized land became used for the timber industry and homesteading, as well as railroads and large scale farming, dairy farming, and ranching (Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, 2022). Large urban areas replaced forests, meadows, and gardens. In heavily forested and agriculturally viable areas like the land now known as Indiana, early European settlers were even known to feed their livestock fodder from the unharvested crops that were left behind when tribes were banished from their homes and farms in late fall.

The remaining ceded lands were made available to homesteaders for $1.25 per acre, on condition of a rarely-kept promise to farm the lands for five years. This formed the original economic base that fueled further westward expansion by settlers.

Research the Morrill Act's Land-Grant Universities on the NLIS

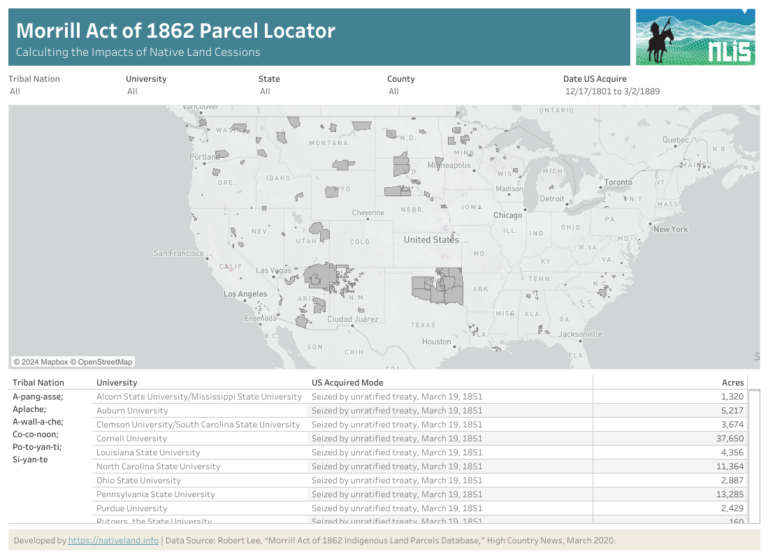

The Native Land Information System (NLIS) hosts a Morrill Act Parcel Locator which draws on patent data from the BLM’s General Land Office (GLO) compiled by High Country News in their March 2020 feature story “Land Grab Universities.” And the second resource that the NLIS provides is the Lost Agriculture Revenue Database that calculates up to 177 years of unrealized Agriculture Revenue for every major Native land cession.

In present day Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota, 137,911.5 acres of land, expropriated from several Chippewa and Ottowa bands, account for 36% of the land sold for the Purdue University land grant. Of that land, 18,163 acres were ceded by treaty on September 24, 1819, and 18,546 acres on July 29, 1837, from the Chippewa in present-day Wisconsin. On March 28, 1836, 60,248 acres were ceded by treaty from the Chippewa and Ottawa nations collectively.

The 1837 treaty facilitated a growing timber industry in territories newly inhabited by homesteaders, where numerous tributaries fed into the Mississippi River from the East, securing access to Chippewa, Sioux, and Winnebago Lands. The discovery of copper ore near Lake Superior prompted another treaty with the Chippewa in 1842. With the Treaty of LaPointe in 1854, the remaining lands south of Lake Superior were ceded and reservations were officially set aside for several Chippewa bands (Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, 2022).

“Winter on Madeline Island.” Original photo by Aubree Herrick, digitally edited by Aliyah Keuthan

"a pan-indigenous movement" is necessary to propel the level of government commitment to do this. The #LandBack movement could be precisely the kind of "pan-indigenous movement" to which Mireles refers. The momentum behind this broad indigenous movement is driven by traditional spiritual and cultural connections to ceded and seized lands.

In light of extreme economic disparities, centuries of dispossession, forced food dependency, continual displacement, and fragmentation of reservation lands, it hardly seems an adequate response for present-day university communications to merely include a brief verbal or written acknowledgment of the Native nations upon whose expropriated lands their institutions of higher learning rest (Wilkie, 2021). Words shared by college officials or added as a postscript in inter-college e-mails are gestures of respect, but much more is needed. A step implies action. More action is necessary to make Native nations whole once again, and to heal ancient, traditional, and ceremonial disconnections caused by the removal of Native peoples from their homelands. Tangible resources can and must be available for Indigenous nations, communities, and tribal colleges to thrive and excel sustainably.

The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act (June 18, 1934), largely ended the privatization and liquidation of treaty lands, protecting them through federal trust status on reservations for specific tribes and bands. A 1935 supplementary report of the Land Planning Committee to the Natural Resources Board recommended restoring 25 million acres, nearly 50% more than their present-day holdings, to enable tribes enough land to be self-sufficient (Wilson, 1935)—but despite this well-researched recommendation, the Federal Government restored only 4 million acres under the IRA—much of it marginal lands (Philp, 1983).

Ernesto Mireles, Professor of Social Justice at Prescott College in Arizona, suggests that effective legislation must benefit all indigenous tribes, not just a few individuals. According to Mireles, “a pan-indigenous movement” is necessary to propel the level of government commitment to do this. The #LandBack movement could be precisely the kind of “pan-indigenous movement” to which Mireles refers. The momentum behind this broad indigenous movement is driven by traditional spiritual and cultural connections to ceded and seized lands. These connections provide the foundation for widespread collective indigenous support of regenerative, organic agricultural and forestry programs, and shared urban gardens, caring for sacred sites and shared spaces (Dooley, 2021).

Look for future articles by Aliyah Keuthan about food sovereignty and related regenerative ag and forestry projects around the Great Lakes in connection with the LandBack movement and restoration of Native lands to tribes.

Aliyah Keuthan is from West Central Indiana. She has traveled extensively throughout the US and globally, and was an Assistant Editor for the Journal of Sustainability Education (JSE) at Prescott College in Arizona. Aliyah is currently a freelance writer.

Written by Aliyah Keuthan

Edited by Emma Scheerer

Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. (n.d.). Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. https://dpi.wi.gov/amind/tribalnationswi/badriver

Bartecchi, D. (2020, November 9). The General Allotment Act of 1887 Crippled Native Agriculture for Generations. The Native Land Information System. https://nativeland.info/topics/native-agriculture-land-use/general-allotment-act-of-1887/

Beem family history written by Captain David Enoch Beem of the US Army, Indiana regiment. Aliyah Keuthan is a descendant of the Beem family of Owen County, Indiana, one of the first European families to settle in that area.

Hipp, J. S., & Martin, M. V. (2018). A Time for Substance: Confronting Funding Inequities at Land Grant Institutions. Tribal College Journal, 29(3). https://tribalcollegejournal.org/a-time-for-substance-confronting-funding-inequities-at-land-grant-institutions/

(At time of publishing). Michael V. Martin, Ph.D., is the President of Florida Gulf Coast University, and Janie Simms Hipp, J.D. (Chickasaw), is a Professor of Law and Director of the Indigenous Food and Agriculture Initiative at the University of Arkansas.

Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, S. 3645, 73d Cong., 2d Sess. (1934).

Winona LaDuke, an enrolled member of the Mississippi Band Anishinaabeg, lives and works on the White Earth Reservation. The environmental activist, among other projects, has been a strong proponent for protecting wild rice from genetic alterations.

Lost Agriculture Revenue from Ceded Native Lands. (n.d.). The Native Land Information System. https://nativeland.info/dashboard/lost-agriculture-revenue-from-ceded-native-lands/

Morrill Act of 1862 Parcel Locator: Calculating the Impacts of Native Land Cessions. (n.d.). The Native Land Information System. https://nativeland.info/dashboard/morrill-act-of-1862-parcel-locator-dashboard/

Personal communication with Ernesto Todd Mireles, professor of Social Justice studies at Prescott College, Prescott, Arizona.

Philp, K. R. (1983). Termination: A Legacy of the Indian New Deal. Western Historical Quarterly, 14(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.2307/968814

Wilkie, S. (2024, January 24). So you want to acknowledge the land? Some notes on a trend, and what real justice could look like. High Country News. https://www.hcn.org/issues/53.5/indigenous-affairs-perspective-so-you-want-to-acknowledge-the-land