By Aliyah Keuthan

Far back into the collective memory of the Ojibwe people is the Anishinaabeg origin story, Ma’iingan (Wolf) and First Man. Wanawaantanegiizhik, John Johnson Sr., a member of the Makwa (Bear) Clan, grandson of Chief Big George Sky, and President of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, recently shared this story with Native Lands Advocacy Project.

“The wolf and first man were once brothers,” stated Johnson. “They were companions. Creator told them to walk together on the earth and to name all the plants and animals. When they finished naming all of the animals and all of the plants, the Creator told Ma’iingan and First Man they could no longer live together; it was time for them to go down separate paths, but from then on, they must look out for each other.” According to Johnson, Wolf strengthened the animals by removing the sick and weak among them, leaving the healthy ones to replenish the forest, while the humans were to see to it that no harm would come to the wolves. “They would always have that relationship even though they no longer lived together as brothers.”

Johnson was elected President of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe in October 2020 and has an active role in the cultural life of the Anishnaabe community. He takes pride in his five grandsons who have learned to sing 72 songs in the Ojibwe language, and are often invited to play drums and sing for events and ceremonies. He is an outdoorsman, hunter, and traditional spearfisher in Wisconsin’s lakes. Johnson’s family provides ongoing cultural and educational support for the Lac du Flambeau Band. His niece, Sarah Thompson, is the Officer of Tribal Historic Preservation, while his brother, Biskabone, Greg Johnson, travels twelve miles off the reservation to the nearest school to teach high school students traditional skills like spearfishing.

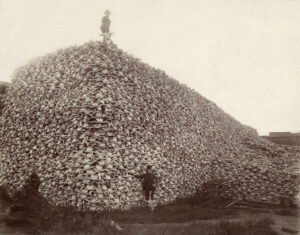

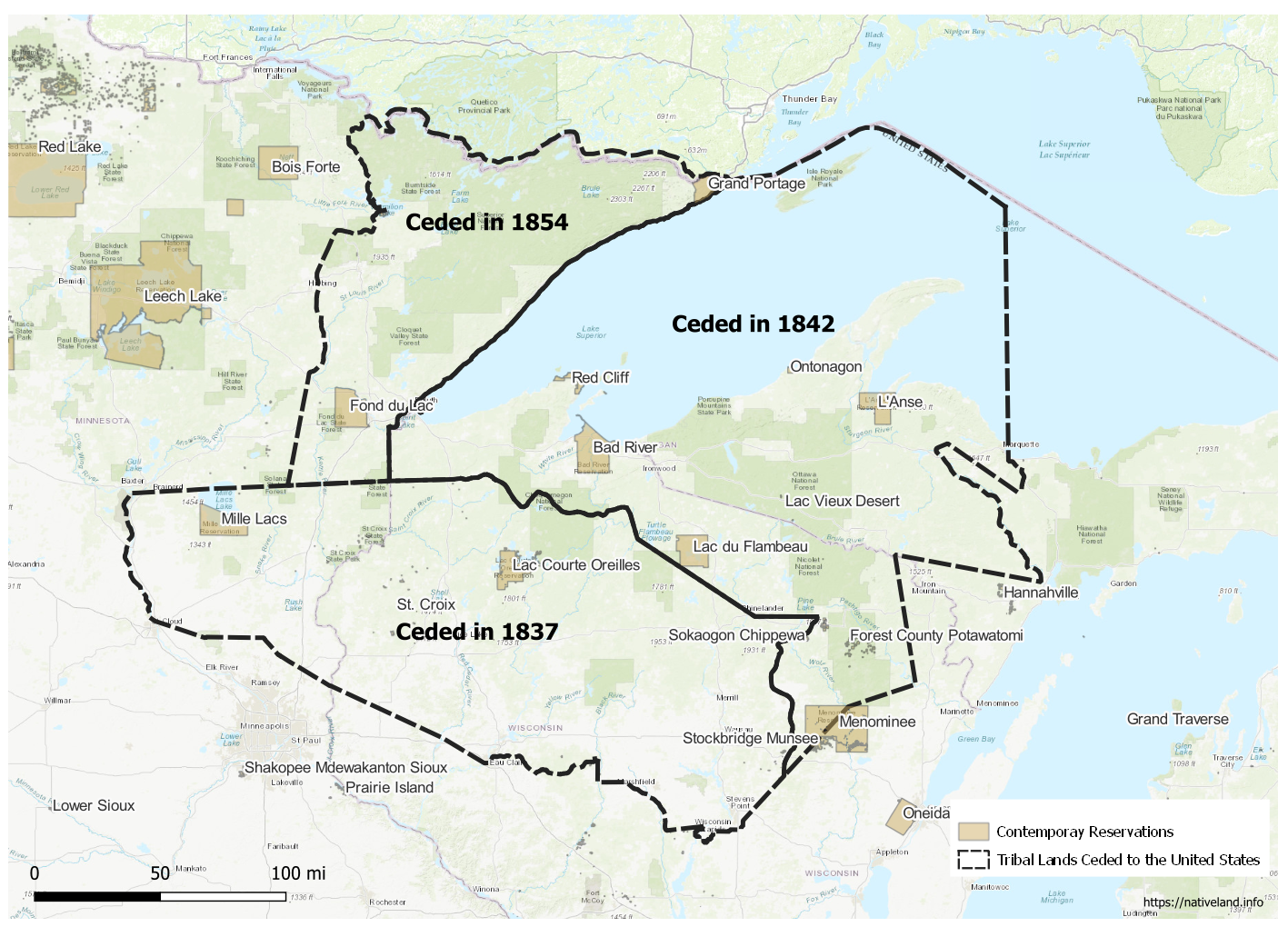

After a century of life on Lake Superior and the waterways where the Anishinaabe bands lived in harmony with nature, and decades of coexisting with European fur trappers, traders, and voyageurs, the Anishinaabe were forced to sign treaties to ensure their survival. In 1837, 1842, and 1854, treaties signed between the US government and the Ojibwe determined boundaries for Ojibwe reservations in what is now the State of Wisconsin (Native Land Information Systems, 2020; Milwaukee Public Museum, 2022). These treaties also secured the continued unhindered usufructuary rights of the Ojibwe to hunt, fish, and gather on former tribal lands in exchange for ceding those lands to the federal government. The Ojibwe have struggled to hold on to those rights ever since 1854.

Almost immediately, Wisconsin began regulating those rights both on and off the reservation. The 1887 General Allotment Act, which, by 1889, opened up unallotted lands to sale and purchase by settlers, encouraged the State of Wisconsin to further limit Ojibwe rights to only reservation lands that were not owned by non-natives (Milwaukee Public Museum, 2022).

In 1983, the Voight Decision, made in the Chicago 7th Circuit Federal Court of Appeals, and upheld later that year by the Supreme Court, recognized the reserved usufructuary treaty rights of the Ojibwe and denounced the wrongful action of the State of Wisconsin in withholding those rights for 129 years. President John Johnson Sr. is also a Chairman of the Voight Task Force Committee of the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC). His duties include working with other Anishnaabeg, and various conservation groups in the State of Wisconsin to develop conservation strategies that are ecologically sound and in line with Anishnaabeg values, culture, and needs. Johnson spoke of the ongoing struggle to be heard when discussing the concerns of the Six Madeline Island Ojibwe bands, of which the Lac du Flambeau is a part.

Johnson said that the demeanor of the Wisconsin Governor and state officials after February 2021 was in stark contrast to those prior to 2021 who were unwilling to listen to the advice and concerns of the Ojibwe regarding conservation and usufructuary rights in Northern Wisconsin.

- J. Johnson Sr., personal communication, March 15, 2022

Johnson said that the demeanor of the Wisconsin Governor and state officials after February 2021 was in stark contrast to those prior to 2021 who were unwilling to listen to the advice and concerns of the Ojibwe regarding conservation and usufructuary rights in Northern Wisconsin. This turnabout was evident in the dispute the Ojibwe had over the Wisconsin wolf hunt. In 2004, an outdated Wisconsin Executive Order, #39, allowing for hunting and trapping of wolves, outraged the Anishinaabe people as well as environmentalists and conservationists.

In 2013, following the Wisconsin mandate for an official wolf hunting and trapping season in 2012 to boost recreational opportunities for hunting enthusiasts, the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, conducted a study to manage wolves “in harmony with the spiritual, biological, and historical significance of Ma’iingan, with the respect that our ancestors would be proud of, while also incorporating biological knowledge,” according to the Director of Conservation for the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, Brian Bisonette (Earthjustice, Declaration by Brian Bisonette, September 30, 2021). The Wisconsin DNR was later reprimanded for not conducting a biological study prior to changing policy. Bisonette informed the court of the discovery of a pregnant wolf found dead within reservation boundaries. She had been shot, possibly illegally by poachers on the reservation, although the wolf could have been shot off the reservation and made her way onto tribal land before she died. This was an example of encroachment by sport hunters on habitat needed not only wolves but also the Ojibwe, whose traditional dietary and health needs come from the same ecosystem.

In February 2021, hunters exceeded the state and tribal limits, killing 218 wolves in three days (Caldwell, M., October 1, 2021). Gray wolves had been given federal protection under the Endangered Species Act of 1978. By 2013 the wolves had begun to recover in the Northern Rocky Mountains and Western Great Lakes regions, prompting a lift to protections in a few states including Wisconsin, in 2013. Grey wolves were officially removed from this list in the Fall of 2020, allowing states to manage the wolf populations (N. Rott, NPR/WNIU, 2020). The GLIFWC was to be part of the decision making process officially, but in practice, not well received by state governing bodies, according to Johnson.

Lac du Flambeau President Johnson understands all too well that the rights of the Ojibwe to be part of the decision-making process, concerning lands where wild foods are available, are essential to the sustainability of the tribe. He explained that traditional knowledge, with regards to hunting, fishing, gathering, and wildlife management. are essential parts of Ojibwe culture that have ensured the survival of their people (Caldwell, M., October 22, 2021). In his official declaration in the U.S. District Court, supporting the injunction against the Wisconsin wolf hunt, Johnson explained that the Ojibwe rely on hunting, fishing, and gathering for their nutritional needs (Earthjustice, Declaration by John Johnson Sr., September 30, 2021). According to Johnson, the forests on and around the Lac du Flambeau reservation lands are essential for supporting the abundant wildlife and traditional native plants necessary for the well-being of the people.

Interconnection between species such as the relationship between wolves, mice, and deer in the forest ecosystem is the foundation of a viable habitat.

J. Johnson Sr

The wolf, a keystone species, has a symbiotic relationship with other species throughout its ecosystem. Johnson described how wolves help to manage the deer population and keep the herd strong. He stated that when the Wisconsin wolf hunt began, a drastic reduction in the wolf population caused an increase in the rodent population. A disease carried by mice spread to the deer, which were then hunted and consumed by humans. Johnson pointed out, that the wolves were blamed for the decrease in the deer population, but more deer were killed by sickness from the diseased rodents, than by wolves. Interconnection between species such as the relationship between wolves, mice, and deer in the forest ecosystem is the foundation of a viable habitat.

Native Plants and Addressing Habitat Loss

As vital parts of the forest ecosystem, native plants also play an important role in Ojibwe culture and survival. Johnson referred to the maple tree as “the strongest tree in the forest, because,” he said, “you can tap the maple tree for its sap and it won’t hurt the tree.” He joked, “we put maple syrup on everything…potatoes, wild rice…”

Johnson continued, “I put asema, tobacco, on the ground under the maple tree, every morning when the sun comes up… starting on the East side of the maple tree… then South, West, and North.” Johnson’s Ojibwe name, Wanawaatanegiizhik, means When the Night Meets the Morning Sky. He explained, “I wake up every morning before sun-up. I offer asema, and I pray. A real Native American always prays for himself last”

"The birch," said Johnson, "is the second strongest tree in the forest - the paper birch. If you are thirsty and there is no water around, you can tap the birch tree and drink its sap and the birch will still be strong. We use the bark for making baskets. Bark from the birch was used for making canoes. The long narrow shape of the birch bark canoe wouldn't damage the rice plants when we harvested the wild rice." Johnson also shared, "Some native plants provide traditional herbal medicines,"

J. Johnson Sr.

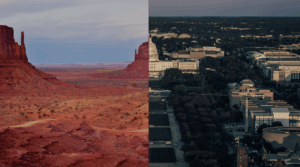

Gathering wild herbs from the woods for teas to share with elders is a favorite activity on the Bad River Reservation, and is part of the experiential education partnership with the local agricultural extension. Small organic farms and gardens are popular in parts of Wisconsin, and there is growing interest in regenerative forestry as well. Student members of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe volunteer alongside local organic gardeners and community organizers at the Madeleine Island Community Garden Project, to share techniques of organic gardening (Dooley, K. 2021). Learning about organic gardening, regenerative food forestry, and gathering of traditional forest herbs is part of the food sovereignty goals of the Ojibwe, but in a subsistence culture, food sovereignty depends a great deal on unhindered access to large expanses of healthy, biodiverse, intact, wild habitat where wild foods can be harvested. Habitat fragmentation and depletion are two of the greatest threats to the subsistence culture of the Ojibwe.

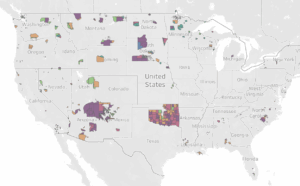

The map above displays intact habitat (shades of green) and habitat loss/fragmentation caused by intensive agriculture (brown and yellow) and urbanization (red and pink) for Anishnaabe reservations.

While the Ojibwe have effectively worked to mitigate habitat loss on their reservation lands, the continual wave of land development off the reservations in surrounding and overlapping counties has contributed to overall habitat degradation and loss, thereby impacting Ojibwe usufructuary rights on treaty lands off the reservations.

In the years from 2001 to 2020, 403,000 hectares of tree cover were lost in the State of Wisconsin, a 5.6% decrease from the year 2000, according to Global Forest Watch (April 11, 2022). Statistics for the year 2020 show that the State lost 30.6 kha. Tree cover loss in three Northern Wisconsin counties mirror the loss of the State. From 2001 to 2020, Ashland county lost 8.72 kha, a 3.6% decrease, Bayfield county lost 30.4 kha, a 9.1% decrease, and Vilas county lost 15.3 kha, a 7.3% decrease.

In 2004, forestry experts cited loss of large-block forest land and fragmentation as obstacles to sustainable forest ecosystem conservation and management, caused by urban development, building of new roads, and agriculture. The downscaling of large blocks of forest land to gradually diminutive parcels, ultimately led to the introduction of invasive species by new forest land owners, who were unaccustomed to conserving native biodiversity, according to Lee Bergquist (September 23, 2004).

Forestry and Agriculture Revenue

The timber industry has contributed to the loss of old-growth forests. In the 1800s the average hemlock tree was 180 years old, while now the oldest trees range in age from 20-80 years (Bergquist, L., September 23, 2004). Today, sprawling manufacturing and food processing complexes, international mining ventures, shopping centers and housing developments, highway infrastructure, utility and energy production facilities, and oil and gas pipelines, all have chiseled away native forest habitat, contributing heavily to degradation and depletion of biodiversity, from large mammals to earthworms. Even efforts toward creating green corridors for wildlife met with the same obstacles that caused the deforestation in the first place.

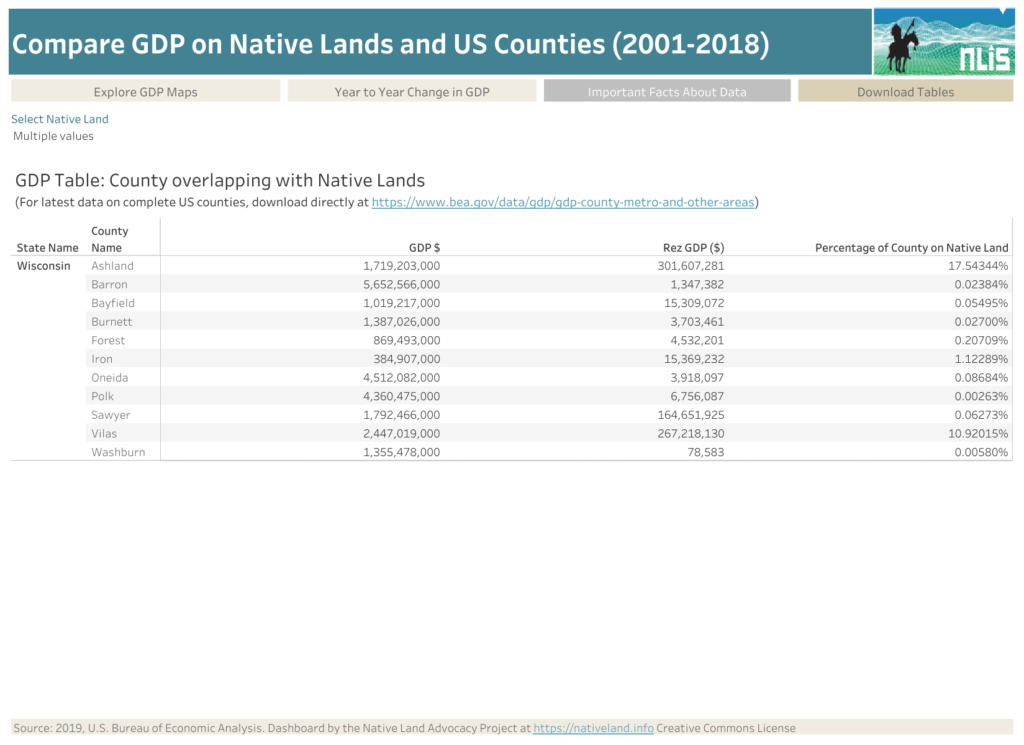

Additionally, the NLIS chart below shows growth in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the Ag/Fish/Hunting/and Forestry sectors, with agriculture and forestry listed as contributors to habitat loss, for each county overlapping the Six Madeline Island Ojibwe Bands, the GDP for each band, and the percentage of each county that overlaps reservation land. Growth in the GDP for these sectors alone rose from $5,678,271.18 in 2012 to $6,139,245.68 in 2018.

Growth in the Ag/Fish/Hunting and Forestry sectors coincides with agricultural intensification, increase in agricultural acres harvested, increase in food processing revenue, and an increase in revenue from timber products. Statistics from the State of Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection (DATCP) show that Wisconsin’s 64,100 farms account for $104.8 billion in revenue and 14.2 million acres of land use in the state. About one tenth of the farms are dairy farms, with cranberries and tart cherries claiming 20,800 acres (April 11, 2022). A study by the National Alliance of Forest Owners stated that in 2016 there were 16.5 million acres of timberland in Wisconsin, of which 11.5 million acres are privately owned. Timber sales reached $21.6 billion in 2016, with a recent report showing a 10% increase. Timberland owners typically consider a long-term commitment to be 20-30 years.

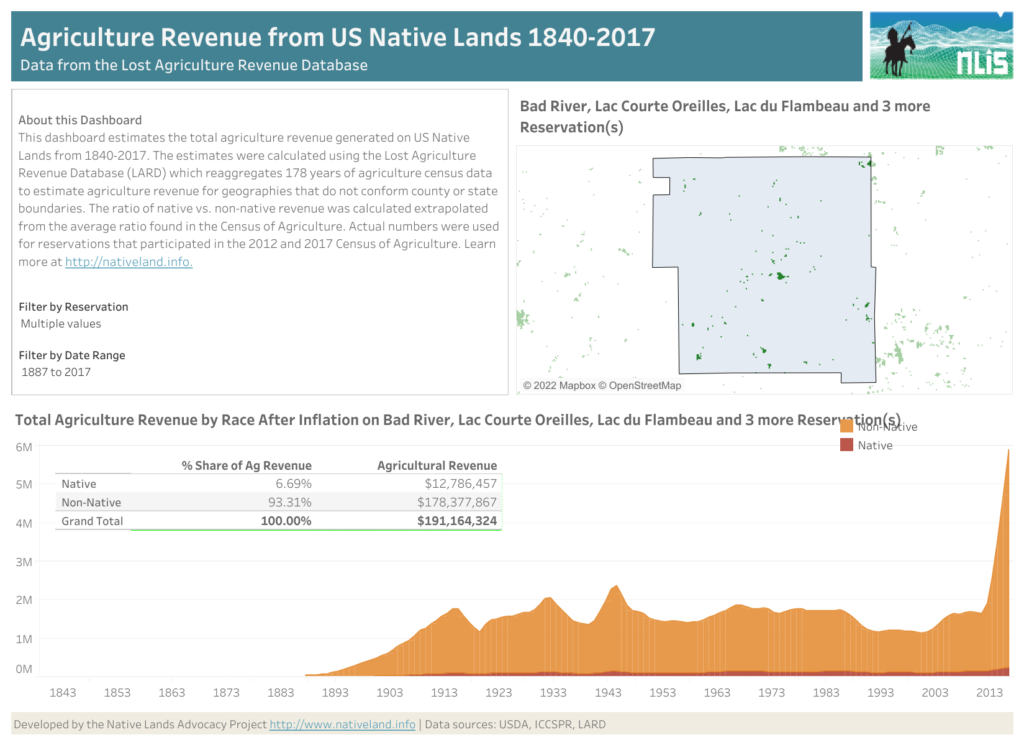

Moreover, agricultural data for 2018 showing the total agricultural revenue for natives and non-natives on Northern Wisconsin’s reservations and trust lands, reveals the vast contrast between non-native production farming revenues, and revenues correlating to Ojibwe agricultural practices, centered mainly around subsistence and localized farming (NLIS Agricultural Revenue from Contemporary US Native Lands, July 20, 2021).

- Lac du Flambeau – native $39,238 / non-native $245,507

- Lac Courte Oreilles – native $174,730 / non-native $1,093,270

- Red Cliff – native $17,914 / non-native $112,086

- Sokaogon (Mole Lake) – native $4,636 / non-native $29,005

- St. Croix – native $5,142 / non-native $32,173

- Bad River – native $0 / non-native $4,146,000

What Might This Mean for the Ojibwe?

The decreased acreage, habitat destruction, and general disparity is counterintuitive to the Trust Doctrine, which affirms it is the responsibility of the federal government to protect Native lands and assets to ensure they are used for the benefit of tribes. It also reflects different values and lifestyles, corporate industrial vs. Indigenous subsistence. Only with the ongoing dialogue and collaboration between State legislators, DNR and NRB officials, the GLIFWC, and Ojibwe tribal leaders and members, as well as support from federal agencies for the Ojibwe, can there be hope of ensuring that the next generations will care for nature so nature can continue to care for the next generations.

Never take more than you need... if you have more than you need, give some away.

Chief Big George Sky (Grandfather of J. Johnson Sr.)

Johnson recalled the words of his Grandfather, Chief Big George Sky, who told him, ” Never take more than you need…if you have more than you need, give some away.”

Interested in Learning More About Habitat Protection?

Check out our new “Preserving Intact Habitat on US Native Lands” storymap that

- Contextualizes intact habitat protection for Tribes

- Provides helpful resources for Tribe to utilize in their own intact habitat planning

- Provides in-app demos of these resourceful tools!

References

Bergquist, L. (September 23, 2004). Forests recovering, but threats loom (WI). Milwaukee Journal Sentinel; in Institute for Agriculture & Trade Policy News. Retrieved from: https://www.iatp.org/news/forests-recovering-but-threats-loom-wi

Caldwell, M. (October 1, 2021). Wisconsin Tribes Seek Court Order to Stop November Wolf Hunt: Six Ojibwe tribes file motion for preliminary injunction against the state. Earthjustice. Retrieved from: https://earthjustice.org/news/press/2021/wisconsin-tribes-seek-court-order-to-stop-november-wolf-hunt

Caldwell, M. (October 22, 2021). Wisconsin Ojibwe Tribes Applaud State Court’s Decision Prohibiting Department of Natural Resources from Issuing Licenses to Hunt Wolves. Earthjustice. Retrieved from: https://earthjustice.org/news/press/2021/wisconsin-ojibwe-tribes-applaud-state-courts-decision-prohibiting-department-of-natural-resources-from-issuing

Dooley, K. (September 3, 2021). Growing food sovereignty on the shores of Lake Superior. In These Times.

Retrieved from:

https://inthesetimes.com/article/anishinaabe-food-sovereignty-lake-superior

Earthjustice (September 30, 2021). Declaration of Brian Bisonette in support of motion for preliminary injunction to stop Wisconsin from holding a wolf hunt in November 2021. Retrieved from: https://earthjustice.org/sites/default/files/files/lco_declaration_-_bisonette_executed.pdf

Earthjustice (September 30, 2020). Declaration of John Johnson, Sr. in support of motion for preliminary injunction to stop Wisconsin from holding a wolf hunt in November 2021. Retrieved from: https://earthjustice.org/sites/default/files/files/lac_du_flambeau_declaration_-_johnson_executed.pdf

Earthjustice (January 14, 2021). Groups challenge Trump administration over gray wolf delisting:

Response to outgoing administration removing Endangered Species Act protections from the gray wolf. Retrieved from: https://earthjustice.org/news/press/2021/groups-challenge-trump-administration-over-gray-wolf-delisting

Global Forest Watch (April 11, 2022). Location of tree cover loss in Wisconsin, United States. Retrieved from: https://gfw.global/3jqcZtZ

Mentzer, R. (April 30, 2019). Report says Wisconsin forestry industry on the upswing: Report based on data from US Census Bureau, Bureau of Economic Analysis, Forest Service, Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved from: https://www.wpr.org/report-says-wisconsin-forestry-industry-upswing

Milwaukee Public Museum (2022). Spearfishing Controversy. Milwaukee Public Museum’s Wisconsin Indian Resource Project. Retrieved from: https://www.mpm.edu/educators/wirp/nations/ojibwe/spearfishing-controversy

Native Land Advocacy Project (February 24, 2021). Order no. 3335 Reaffirmation of the Federal Trust Responsibility to Federally Recognized Indian Tribes and Individual Indian Beneficiaries. Retrieved from: https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/migrated/news/pressreleases/upload/Signed-SO-3335.pdf

Native Land Information System (July 30, 2021). Agriculture Revenue from Contemporary US Native Lands. Retrieved from: https://nativeland.info/blog/dashboard/agriculture-revenue-from-contemporary-us-native-lands/

Native Land Information System (March 31, 2022). Compare Native Lands vs US Counties GDP by Industry (2001-2018). Retrieved from: https://nativeland.info/blog/dashboard/compare-native-lands-vs-us-counties-gdp-by-industry-2001-2018/

Native Land Information System (December 24, 2020) Indian Land Cessions in the United States, 1784-1897. Retrieved from: https://data.nativeland.info/dataset/indian-land-cessions-in-the-united-states-1784-1894

Native Land Information System (2019). Land Covers & Changes on US Native Lands. Retrieved from: https://nativeland.info/blog/dashboard/land-covers-on-native-lands-in-the-coterminous-united-states/

Native Land Information System (April 9, 2022) Native Lands Areas 1887-1984. Retrieved from: https://nativeland.info/blog/dashboard/native-lands-areas-1887-1984/

Native Land Information System (April 11, 2022) What’s Growing on Native Lands in the Coterminous United States. Retrieved from https://nativeland.info/blog/dashboard/whats-growing-on-native-lands-in-the-coterminous-united-states/.

Rott, N. (October 29, 2020). Gray Wolves To Be Removed From Endangered Species List. In National Public Radio/WNIU. Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/2020/10/29/929095979/gray-wolves-to-be-removed-from-endangered-species-list

State of Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection (April 11, 2022). Wisconsin Agricultural Statistics. Retrieved from: https://datcp.wi.gov/Pages/Publications/WIAgStatistics.aspx

United States District Court Western District of Wisconsin; Civil Case No.: 3:21-cv-00597; Plaintiffs’ Motion for a Preliminary Injunction Pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 65; Document #: 17 Filed: 10/01/21. Retrieved from: https://earthjustice.org/sites/default/files/files/ojibwe_tribes_motion_brief_for_preliminary_injunction.pdf

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Office of Communications (February, 11, 2022). Wisconsin Wolf Hunting Update. Retrieved from:

https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/newsroom/release/53316

Personal Interviews:

John Johnson Sr., personal communication with Aliyah Keuthan, March 15, 2022.

Photo Credits:

Jean Beaufort (Uploaded 3/31/2022). Gray Wolf Portrait: Common gray wolf resting in the wilderness. License: CC0 Public Domain. Free Download. Retrieved from: https://www.publicdomainpictures.net/pictures/160000/velka/gray-wolf-portrait.jpg

David Selbert. (Downloaded March 31, 2022). Furry lynx in nature near tree twigs. Retrieved from: https://www.pexels.com/photo/furry-lynx-in-nature-near-tree-twigs-6468079/

David Selbert. (Downloaded March 31, 2022). A squirrel munching on a cone in a pine tree. Retrieved from: https://www.pexels.com/photo/a-squirrel-munching-on-a-cone-in-a-pine-tree-9542698/

Roland W. Reed. (1908). The Fisherman. Wiki Commons. Retrieved from: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/The_Fisherman%2C_Roland_W._Reed%2C_1908_Img018.jpg/459px-The_Fisherman%2C_Roland_W._Reed%2C_1908_Img018.jpg