Today, the US Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) holds 66 million acres of lands in trust for various Indian tribes and individuals. Approximately 46 million acres (69%) of this land is used for farming and grazing by livestock and game animals. However, Native Americans are not the primary beneficiaries of agriculture on their lands. According to the 2017 USDA Census of Agriculture for American Indian Reservations, which collected data for 75 Reservations, Native Americans only captured 12.89% of the Agriculture revenue generated on their lands vs. 87.11% captured by non-natives. Additionally, non-natives controlled 86.33% of harvested croplands and 72.16% of the livestock. The agricultural disparity endemic on Native American reservations can be traced back to the passage of General Allotment Act of 1887 and subsequent amendments that ceded and opened up native lands to non-native farmers and ranchers. While the Federal Government has acknowledged the failures of its policies on native lands, it has never addressed them to the extent necessary which explains why the disparity has persisted to this day.

In this post, I will outline the history of agriculture on Native American reservations, the ways the General Allotment act crippled native agriculture by alienating reservation lands from native people through cessions, fee patents, and leasing. Lastly, I will trace the history of the Government’s own recognition of these problems and its failures to take sufficient action per the moral and fiduciary responsibility as affirmed by Congress and the Supreme Court.

Native Agriculture Expanded Rapidly on Reservations Prior to Dawes Act

There is a popular myth that persists in the American psyche that attempts to explain away the great disparity in agriculture between natives and non-natives, claiming that Native American’s “just aren’t good farmers,” or that somehow “farming is not compatible with native culture.” But this myth is nothing more than a convenient way for settlers to attempt to justify the gross injustices of land cessions and exclusionary policies during the reservation era and has no basis in fact. In particular, it erases the deep ecological knowledge that has guided indigenous peoples’ land use and is still embedded in their languages. Numerous accounts of early explorers and mountains of archeological evidence testify of the vast and sophisticated networks of pre-columbian agricultural infrastructure including irrigation works, terraces, raised fields, enhanced soils, dating back to at least 9000 years BP.

“American Indians of Today” produced by Encyclopaedia Britannica Films in 1957 for school use helped shape negative stereotypes about American Agriculture.

In contrast with this myth, early reports of native agriculture on reservations paint a picture of rapid growth in agricultural production. Most notably is the work of Leonard Carlson (1978, 1981 and 1983). His 1981 research utilized agriculture statistics included in the BIA Superintendent Reports from 1877-1904 (1904 is the year when survey work for allotment began on many reservations) and shows strong evidence of rapid growth in agriculture prior to allotment. Carlson argues that:

“Indian farmers appear to have made an impressive start in the years before allotment…Looking first at the acres cultivated per capita by Indians, 18 of the 33 reservations had compounded rates of growth in excess of 10% per year, including four which had growth rates in excess of 20% per year. Nine had rates of growth between 5% and 10% per annum, while three grew at less than 5% and three declined. (Carlson 1981).”

When this data is combined with the statistical data as well as reports from Indian Agents and other accounts from the time, Carlson concluded that:

“[t]aken together, however, the picture which emerges is of a decline in Indian farming after allotment. Indian farmers had smaller farms, smaller incomes and were more vulnerable to economic fluctuations than white farmers. Further, the aggregate data and case studies provide evidence that the gap between Indian and white farmers had widened after allotment” (Carlson 1981).

The problem, according to Carlson (1978) was that:

“the course of allotment was determined by non-Indian economic interests. This conclusion does not imply, however, that Indian policy was a thinly veiled scheme to expropriate Indian land. Rather, it shows that the open-ended federal policy was bent and shaped by outside economic interests.” In particular, those interests who pushed to open Indian lands up to leasing and fee-patenting.

In 1988, the USDA came to a similar conclusion in a study for the task force of the American Indian Agricultural Council by Henry W. Kipp. Also, drawing on the statistical data from annual reports from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the Kipp study concludes that:

“[a]nnual reports from the Commissioner of Indian affairs indicate an expansion of agriculture occurred in the Sioux country during the late 1870’s and through the 1880s. On Devils Lake (Santee Sioux) Reservation, farming was done by Indians supervised by the Agent. . . cultivated acres increased from 1,500 in 1882 to 5,500 in 1889. On Yankton Sioux land of southeastern South Dakota, Indian farming increased” (Kipp 1988).

Hakansson (1997) drawing from data from the Annual Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the Pine Ridge Reservation comes to a similar conclusion as Carlson and Kipp,

“[e]ven before allotment, however, some Oglalas had been farming on the reservation as a communal land base. Between 1882 and 1890, these first attempts at farming had been relatively successful” but goes on to argue that these efforts were stymied by severe drought in the 1890s (Hakansson 1997).

So if native agriculture was in fact rising in early reservation days, what has led to its demise and the inequality we can observe today? The answer is to be found in land tenure policies.

How the Dawes Act Fueled the Disparity in Agriculture on Native Lands

From our research, the Dawes Act crippled agriculture development on native American Reservations in three distinct ways:

- It greatly diminished the land base of Native Americas through cessions of so called “surplus lands.”

- It made it possible to issue native land owners “fee patents” on their allotments, making them subject to taxation and sale.

- It opened up Native Lands to be leased by Non-natives and Native landowners were not fully compensated

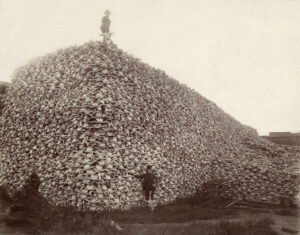

1) The Dawes Act greatly diminished the land base of Native Americans

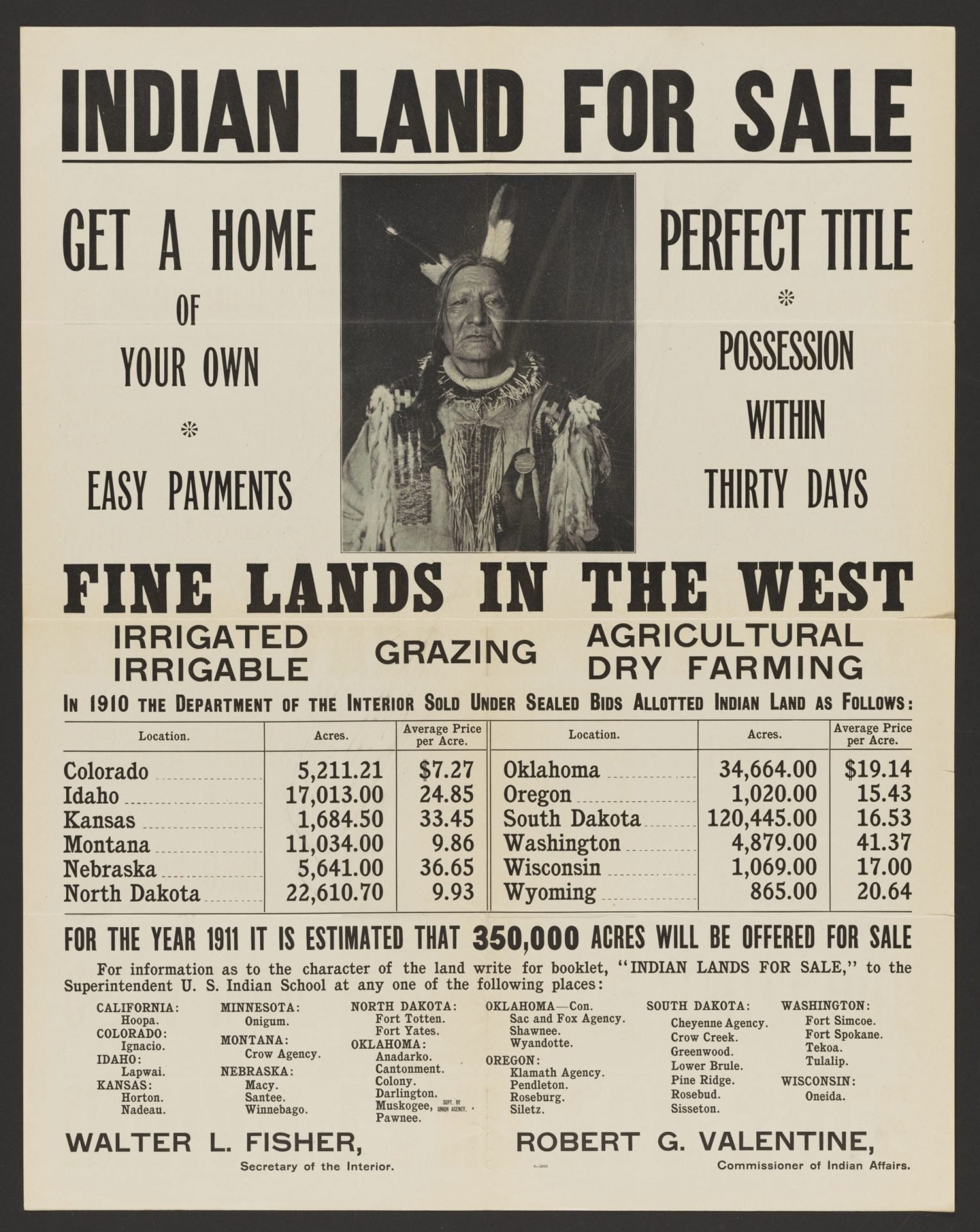

Along with allotting Reservation lands into parcels there was also a provision that any land remaining after allotment would be considered “surplus” and would be ceded to the public domain OR would remain part of the Reservation but opened up to homesteaders. During the 47 years of the Dawes act, approximately 60,000,000 acres of so-called “surplus” lands were alienated and oftentimes opened-up to homesteaders. The alienation of these lands under the Dawes act occurred in two ways. The first were surplus lands that were “Ceded” after individual allotment to all qualifying individuals. This means that the original land base was larger than the total acres of allotted land. Approximately 38,000,000 acres were alienated/taken aways through this mechanism (Wilson 1935) and defined, for the most part, the current boundaries of Native American Reservations today. Surplus lands that were not “ceded” were opened up to homesteaders and tribes were supposed to be remunerated as they were settled by homesteaders (Wilson 1935). Approximately 22,000,000 acres of land were alienated through this process.

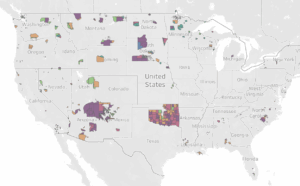

Data Dashboard: Native Lands Areas 1887-1984

2) The Dawes Act made it possible to issue native land owners “fee patents” on their allotments, making them subject to taxation and sale.

According to Section 5 of the Dawes Act signed into law February 8th, 1887, allotments that were issued to Tribal members were to be held in trust by the United States Government for a period twenty five years. This protected the land from taxation and sale. After this period, the Government would issue a patent to the allottee or their heirs. The act reads as follows:

“United States does and will hold the land thus allotted, for the period of twenty-five years, in trust for the sole use and benefit of the Indian to whom such allotment shall have been made, or, in case of his decease, of his heirs according to the laws of the State or Territory where such land is located, and that at the expiration of said period the United States will convey the same by patent to said Indian, or his heirs as aforesaid, in fee, discharged of said trust and free of all charge or incumbrance whatsoever: Provided, That the President of the United States may in any case in his discretion extend the period”.

It took less than five years before this provision was amended to remove the restriction on issuing fee patents on inherited lands. The Act of May 27, 1902 (32 Stat. 245-275) otherwise known as the Dead Indian Act allowed the heirs of a deceased allottee to sell the inherited lands after being issued a fee patent by the Secretary of Interior. Five years later this authority was broadened again with the Burke Act of May 8th, 1906 (34 Stat. 182) which expanded the authority by adding the to sell the lands of deceased indians with the proceeds going to heirs. These acts, along with the act of May 29th, 1908 (35 Stat. L. 444) and the act of June 25th, 1910 (36 Stat. L. 855-856) were responsible for the sale of over 2,449,736 acres of inherited lands between the periods of 1903 to 1934.

The liquidation of allotted lands began with the the Burke Act of 1906 which authorized the secretary of Interior to remove trust protections and issue fee patents to Native Americans that are considered “competent”. The Act reads:

“Provided, That the Secretary of the Interior may, in his discretion, and he is hereby authorized, whenever he shall be satisfied that any Indian allottee is competent and capable of managing his or her affairs, at any time to cause to be issued to such allottee a patent in fee simple, and thereafter all restrictions as to sale, incumbrance, or taxation of said land shall be removed and said land shall not be liable to the satisfaction of any debt contracted prior to the issuing of such patent”:

Just one year later, the Act of March 1, 1907 (34 Stat. L. 1015-1018) expanded this authority by giving the Secretary the power to approve the sale of lands of allottees considered “non-competent.”.

“That any non-competent Indian to whom a patent containing restrictions against alienation has been issued for an allotment of land in severalty, under any law or treaty, or who may have an interest in any allotment by inheritance, may sell or convey all or any part of such allotment or such inherited interest on such terms and conditions and under such rules and regulations as the Secretary of the Interior may prescribe.”

The power of the Secretary of Interior was further expanded through the acts of May 29th, 1908 (Stat. 35 L. 444) and June 25th, 1910 (36 Stat. L. 855-856) and Feb. 14th, 1913 (37 Stat. L. 678-679). Combined, these acts accounted for the sale of over 1,280,526 acres of allotted land between 1908 and 1934 and caused a flood on non-native settlers onto native lands.

Despite the original intent of the Dawes legislation to enable Native Americans to “own the lands he cultivates,” it was widely understood by government officials at the time that issuing a fee patent was almost a guarantee that those lands would be liquidated within a few years (McDonnell and 1952- 1991; Carlson 1983; Macgregor, Hassrick, and Henry 1946; Means 2007; Hakansson 1997; Wilson 1935). In his 1913 Annual Report, the Superintendent of the Pine Ridge Reservation writes:

“It is still the conviction of this office that the issue of a patent in fee for a portion of an Indian’s land who is judged as being competent or near-competent, is the proper procedure in dealing with the land question among the Indians…Even if the proceeds derived from the dispossession of the land are squandered he still has plenty of land left and he may have learned a few lessons that will prove of value in the future.” (Department of the Interior, Annual Report of the Pine Ridge Agency, SD, August 1, 1913)

Axel Johnson, superintendent for the Omaha reservation noted that only 13% of those who received fee patents used their land productively; 7.1 percent of those who sold their land used the proceeds wisely and; 80% had “little or nothing to show for their lands” (McDonnell and 1952- 1991).

While the practice of forced-fee patenting was supposed to end with the Wheeler-Howard Act, the secretary of interior still had the power to issue fee patents to individual land owners upon petition. During the post WWII relocation era where federal policy shifted to encourage Native Americans to move off Reservations and fill the growing need for wage laborers in urban areas of the United States, the BIA approved almost all requests for fee patents. According to Philip (1983) between 1948 and 1957 federal protection was removed from over 2.5 million acres of individual trust lands (Philip 1983).

3) The Dawes Act opened up native lands to be leased by non-Natives

The leasing of Indian Lands by the Federal Government dates back the the the Act of February 28, 1891 which amended the original Dawes act to give the Secretary of Interior the power to lease the lands of allottees for “reason of age or disability” for a period of 3 years for agriculture purposes, 5 years for grazing and 10 years for mining, The original wording is as follows:

“That whenever it shall be made to appear to the Secretary of the Interior that, by reason of age or other disability, any allottee under the provisions of said act, or any other act or treaty can not personally and with benefit to himself occupy or improve his allotment or any part thereof the same may be leased upon such terms, regulations and conditions as shall be prescribed by such Secretary, for a term not exceeding three years for farming or grazing, or ten years for mining purposes:

Provided, That where lands are occupied by Indians who have bought and paid for the same, and which lands are not needed for farming or agricultural purposes, and are not desired for individual allotments, the same may be leased by authority of the Council speaking for such Indians, for a period not to exceed five years for grazing, or ten years for mining purposes in such quantities and upon such terms and conditions as the agent in charge of such reservation may recommend, subject to the approval of the Secretary of the Interior”.

The original amendment does not provide much guidance what ages are qualify and how “disability” was to be interpreted. However, the 1893 Annual Report from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (P476) explains to how this law was to be interpreted by the Superintendent’s on each reservation:

- The term “age,” as used in said act, is defined to apply to all minors under 18 and all other persons disabled by reason of old age.

- The term “other disability” is defined to apply to:

- Unmarried women

- All married women or widows who have neither husbands nor children in condition to cultivate their land with profit.

- All who are disabled by reason of chronic sickness or incurable physical defect.

- All those who are disabled by native defect of mind or permanent incurable mental disease.

In 1894, the annual Indian Appropriation Act increased the agricultural lease term to 5 years, 10 years for business and mining leases, and permitted forced leases for allottees who “suffered” from “inability to work their land.” Clearly designed to alienate lands from Native Americans, this act dramatically increased the number of leases issued across the country.

The Act of June 25th 1910 further amends the GAA to give the Secretary of the Interior the power to sell the land of deceased allottees or issue patent and fee to legal heirs. This decision is based on a vague determination made by the Secretary of whether the legal heirs are ‘competent’ or ‘incompetent’ to manage their own affairs.

“If the Secretary finds the legal heirs competent to manage their own affairs, and that the lands are capable of partition, he may convey the lands to the heirs and issue them patents-in-fee. If the legal heirs are incompetent, the Secretary is authorized to sell the lands.”

As we can see from the annual reports from the Pine Ridge Agency for that same summer, no time was wasted in this effort.

“During the present summer eighty-six pieces of inherited and non-competent land were advertised for sale.’ (Department of the Interior, Annual Report of the Pine Ridge Agency, SD, August 1, 1910)

The ambiguous designation of ‘competent’ and ‘non-competent’ was not only used by the state to control Indian lands, it was also used to determine how to distribute annuities guaranteed to the Lakotas living on Pine Ridge.

“Our records show that 2294 of the Pine Ridge Indians have received their pro rata shares of tribal trust funds. 1009 received their shares as competents and 1285 as incompetents, incapable of performing manual labor on account of physical disabilities. In the case of the former, the money is paid to them direct to be expended as they may see fit. As the amount is only, in round numbers, $130.00, it is generally expended in living expenses. The money of the incompetents is deposited as Individual Indian Bank Accounts and expended, in the great majority of cases, for medical attention and monthly pensions. (Department of the Interior, Annual Report of the Pine Ridge Agency, SD, August , 1915)

Note that more than half (56%) of the Lakota living on Pine Ridge were classified as “non-competent” and thus did not directly receive their annuity payments. Rather, the administration of the Pine Ridge Agency would use the money “for medical attention and monthly pensions.”

Data Dashboard: The Leasing of US Native Lands by the Bureau of Indian Affairs

The federal government failed to pay native landowners for leases on their lands

Under the Indian General Allotment Act of 1887, 24 Stat. 388, as amended, the Department of the Interior would manage land and leases on that land held in trust for individual Indians. As part of their role as trustee, the department of interior created “Individual Indian Money” (IIM) accounts used to disperse funds generated from lands under their management. In 1996 Eloise Cobell, a native landowner from the Blackfeet Reservation sued the Federal Government in a class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of 500,000 Native Americans arguing that the government was not fully compensating native owners. After 14 years of stalling with disingenuous accounting, racking up millions of dollars in legal fees charged to tax payers, withholding and even destroying evidence (for which the Department of Interior was held in contempt of court), the government finally conceded and agreed to settle with the Plaintiffs. While the defendants argued they were owed as much as $42 billion from 115 years of leases, the government finally capitulated and settled for only $3.2 billion, less than 14% of what was owed. Additionally, only $1.3 billion went to the native land owners, the majority of the remaining funds were used to consolidate lands, a problem created by the federal government’s mismanagement of their trust responsibility.

Government Attempts to Repair Damage Caused by GAA

In 1934, in response to criticism from the Meriam Report and Testimony from people like D.S. Otis, the Federal Government passed the Indian Reorganization Act which, among other things curtailed allotment and fee patenting and enabled tribes to establish western styled governments. The act did very little to curtail leasing aside from limiting leasing to 25 years or less. in 1935 the National Resources Board recommended spending $103 million to acquire 25 million acres of land to contribute to the self-sufficiency of Native Americans. However, because of pressure from white ranchers congress only approved $5 million which was used to acquire 398,189 millions acres of new land. An additional 621,621 acres were restored from surplus lands after allotment and tribes purchased 265,852 from their own funds; a total of only 1,285,662 acres (Philp 1983). Additional purchases of “sub-optimal” lands occurred under the 1934 Taylor Grazing Act which brought number of lands restored to trust to 4 million acres or less than 5% of the pre-Dawes Act acreage restored (Philp 1983).

In 1975, after several high-profile attempts to raise awareness about the dire situation on Reservations by the American Indian Movement, Congress established the American Indian Policy Review Commission. In 1976 the taskforce on Reservation and Resource Development and Protection published their report. In it they acknowledged the disparity in agriculture on reservations, in particular, the policy of leasing. According to the report:

“The BIA’s preference for leasing keeps it from designing an agricultural development program. As a result, lack of capital and technology continue to plague Indian farmers and the BIA continues its leasing activities.”

In 1976 the Committee published its final report stating that:

“over the past 20 years, the Indian agriculture program operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs has fallen into serious decline. Funding levels for the Program have remained static and through inflation have ben reduced to half or les of their former levels.”

In 1993, Congress passed the American Indian Agricultural Resources Management act which empowers tribes to take greater control over the management of their resources and leasing policies. Hover, the policy requires the creation of detailed Integrated Resources Management Plans which have to be renewed every 10 years and few Tribes have met this standard.

Furthermore, Native Americans are still crippled by the land loss under the GAA and reacquisition remains a cornerstone of repairing the damage and enabling self-sufficiency; according to the National Congress of American Indians:

“of the 90 million acres of tribal land lost through the allotment process, only about eight percent has been reacquired in trust status since the IRA was passed in 1934. Still today, many tribes have no land base, and many tribes have insufficient lands to support housing and self-government. And the legacy of the allotment policy, which has deeply fractionated heirship of trust lands, means that, for most tribes, far more Indian land passes out of trust than into trust each year. Most tribal lands will not readily support economic development. Many reservations are located far away from the tribe’s historical, cultural, and sacred areas, as well as from traditional hunting, fishing, and gathering areas. NCAI will continue to advocate strongly for the restoration of tribal lands.”

While Native Americans and Native American Tribes enjoy a degree of political sovereignty, it is compromised by the fact that most tribal lands and resources are held in trust by the Federal Government. Because of this unique relationship, the US Supreme court has repeatedly affirmed and upheld the responsibility that the federal government has to protect the tribal lands and assets and ensure they are used for the benefit of native people. This responsibility the federal government has to native peoples and tribes is known as the Trust Doctrine. In 1977, the Senate report of the American Indian Policy Review Commission described the federal government’s trust obligation as follows:

“The purpose behind the trust doctrine is and always has been to ensure the survival and welfare of Indian tribes and people. This includes an obligation to provide those services required to protect and enhance tribal lands, resources, and self-government, and also includes those economic and social programs which are necessary to raise the standard of living and social well-being of the Indian people to a level comparable to the non-Indian society”.

The United States Bureau of Indian Affair mirrors this doctrine on its website.

“The federal Indian trust responsibility is a legal obligation under which the United States “has charged itself with moral obligations of the highest responsibility and trust” toward Indian tribes (Seminole Nation v. United States, 1942). This obligation was first discussed by Chief Justice John Marshall in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831). Over the years, the trust doctrine has been at the center of numerous other Supreme Court cases, thus making it one of the most important principles in federal Indian law.

The federal Indian trust responsibility is also a legally enforceable fiduciary obligation on the part of the United States to protect tribal treaty rights, lands, assets, and resources, as well as a duty to carry out the mandates of federal law with respect to American Indian and Alaska Native tribes and villages. In several cases discussing the trust responsibility, the Supreme Court has used language suggesting that it entails legal duties, moral obligations, and the fulfillment of understandings and expectations that have arisen over the entire course of the relationship between the United States and the federally recognized tribes”.

Timeline of Criticism of General Allotment Act

The General Allotment Act

Government Opens Native Lands for Leasing

Government Starts Liquidating Reservation Lands

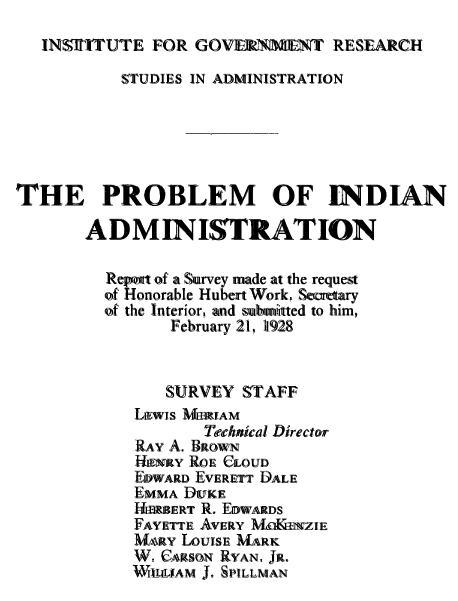

Meriam Report Documents Deprivation Caused by Leasing and Land Sales

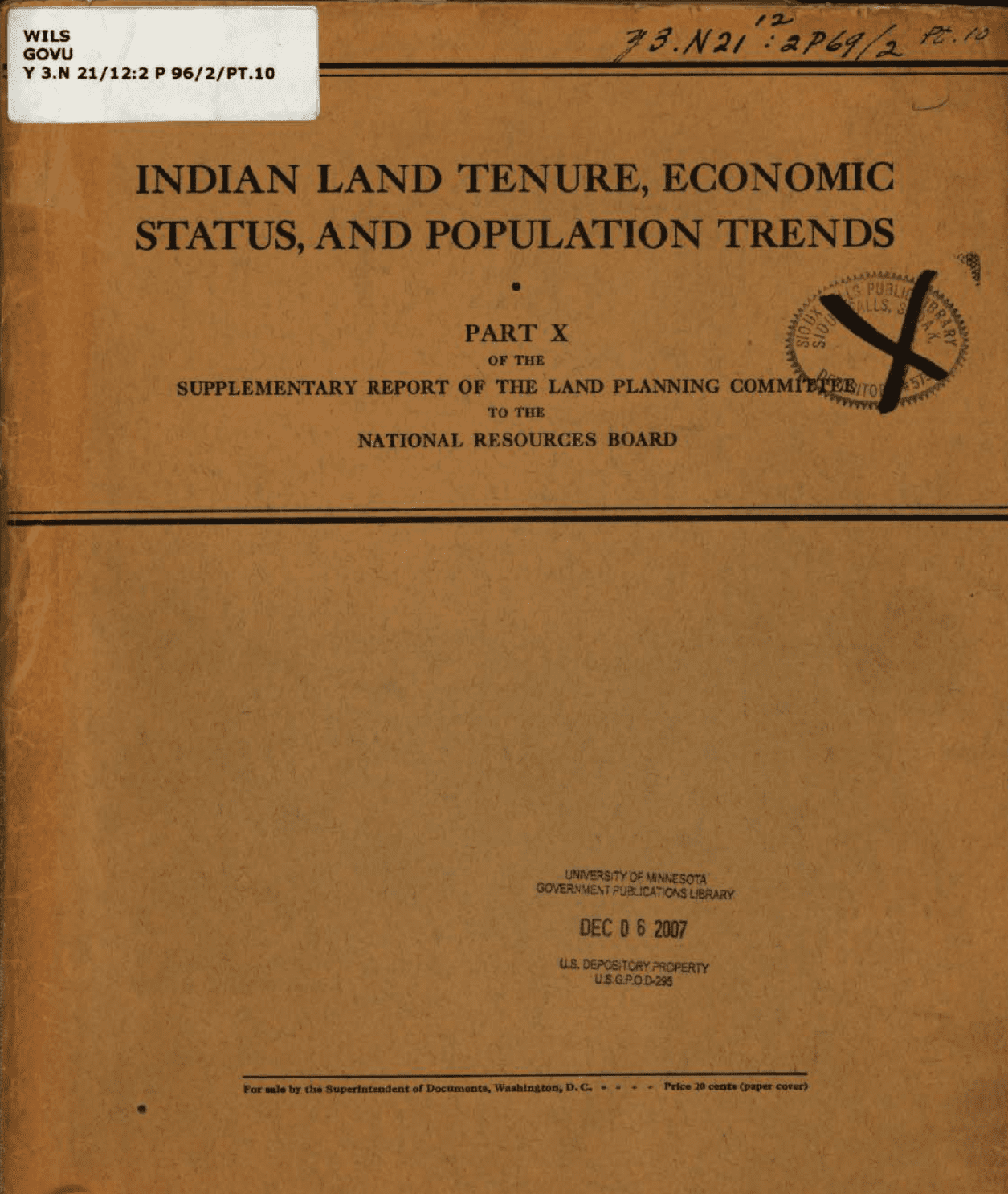

Wilson Report, Again Criticizes Government Leasing and Calls for Restoration of 25 Million Acres

41 Years After Wilson Report Very Little Has Changed

Congress Recognizes Failures of BIA's Agricultural Support

What do you think? Please share your thoughts, experiences, questions, or comments below?