As tribes continue to experience the impacts of climate change on their lands and communities, they are starting to invest more of their resources and planning strategies into protecting and enhancing their soil organic carbon (SOC).

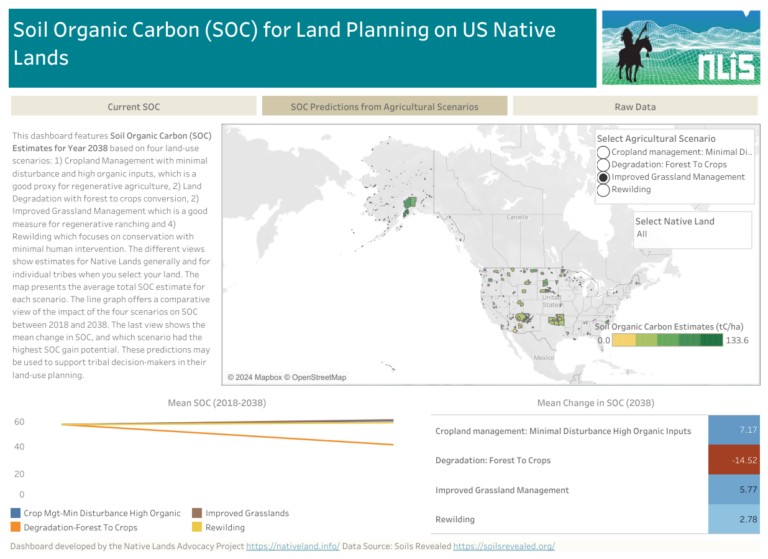

In this blog post, we discuss ways that tribal land caretakers can use our Soil Organic Carbon Dashboard, which summarizes Soil Organic Carbon data for Native land areas sourced from the most recent Soil Survey and the Soils Revealed project. We were also happy to connect with Bryan VanStippen, Executive Director of the National Indian Carbon Coalition (NICC), for his comments on the carbon planning scene in Indian Country.

What is SOC?

For those of us who are not Native soil scientists and are at the headwaters of the carbon planning discussion, we will briefly touch on what SOC is and how Indigenous land practices are equipped for its protection.

Soil organic carbon refers to the measurable component of carbon that is stored in soil organic matter, which is derived from decaying plant and animal material. This carbon is a vital component of soil organic matter and plays a crucial role in soil health and fertility.

For example, SOC positively impacts soil structure and prevents erosion, increasing water storage, nutrient availability, and microbial activity. High levels of SOC are generally associated with fertile soils because they provide a continuous source of nutrients as the organic matter breaks down over time.

Soil organic carbon also has implications for climate change mitigation. Well-managed soils can sequester carbon released by decomposing soil organic matter, storing the carbon in the soil rather than in our atmosphere.

As for enhancing and protecting SOC, how humans interact with their agriculture, forestlands, and other land use activities can positively or negatively impact SOC levels. Knowing this, tribes recognize the necessity for sustainable, traditional land practices, such as regenerative farming, agroforestry and intercropping, cultural burnings, and reduced/no-till farming. Tribes acknowledge that these practices exemplify healthy stewardship of lands and also encourage their soil’s organic carbon content.

Far from being a novel concept to tribal communities, the natural process of SOC demonstrates the land’s ability to self-regulate and heal, given that, as humans, we uphold our responsibilities of proper land care. Since time immemorial, Indigenous peoples have recognized this interconnectedness and have understood the benefits of maintaining a balanced relationship with the land and its soil.

Therefore, Indigenous-holistic approaches to land management remain a steady foundation for carbon planning, even as planning tools and markets continue to expand (as we’ll cover in the following sections).

Tribal Climate Planning With NLAP’s SOC Dashboard

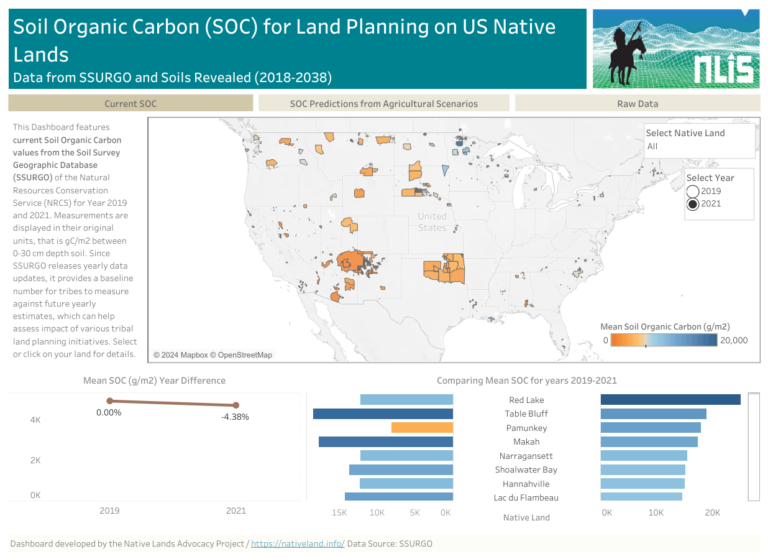

NLAP’s Soil Organic Carbon Planning Dashboard exists for tribes to examine the potential impact of various land practices on their SOC concentration. Our dashboard summarizes key data from NRCS’ most recent Soil Surveys (2019 and 2021) and SOC stock predictions from the Soils Revealed project.

Compiling these two publicly available data sources allows tribes to observe their historic, present, and future SOC concentration according to various agricultural land practices—making this dashboard incredibly useful and relevant for Native land planning and climate adaptation.

On the dashboard’s main page, you can view your reservation’s soil organic carbon values according to the 2019 and 2021 SSURGO data. The measurements of SOC present in the soil are expressed in gC/m2 (grams of carbon per square meter) for a 0-30 cm soil depth.

Start by filtering for your reservation and your preferred year (2019 or 2021) to observe:

- The map view, which shows your reservation’s mean SOC concentration (orange represents lower concentrations of SOC, while blue represents higher concentrations). Hover over your reservation to see the mean SOC concentration, expressed in grams per square meter.

- Differences in your mean SOC values from 2019 to 2021.

Clicking on the next tab, you will be able to view your SOC predictions based on different agricultural scenarios according to data sourced from Soils Revealed.

Soils Revealed is a platform for visualizing how past and future management changes soil organic carbon stocks globally. It is based on the best, and sometimes only, available soil data, information about the environment and computer simulations over time. Projections for the coming decades are based on scenarios issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

‘About Us’, Soils Revealed

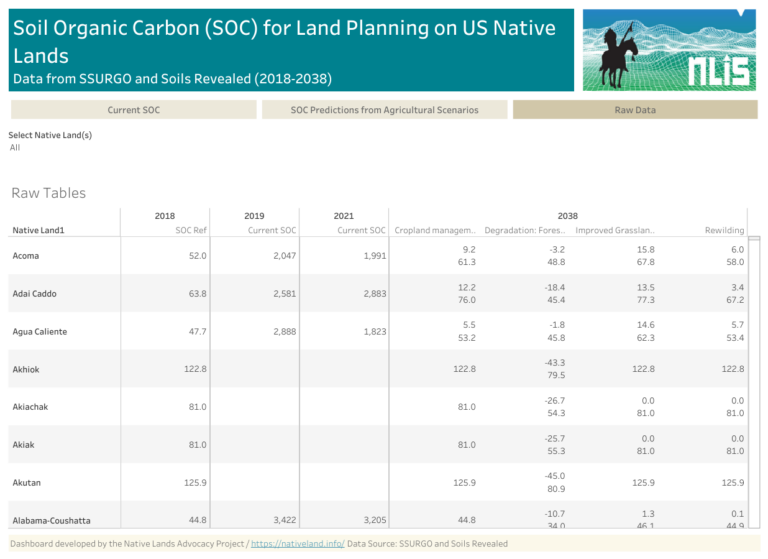

Utilizing these estimates provided by Soils Revealed and applying them to Native land areas uniquely shows us how different land practices might impact specific SOC concentration in tribal geographies. These estimates can be observed over a 20-year period (2018-2038), providing tribes and individual Native land stewards with comprehensive baseline SOC numbers to inform their decision-making.

On this tab, you are able to filter by your reservation to view:

- Projected changes in your land’s mean SOC from 2018 to 2038.

- Projected changes in your land’s mean SOC according to different agricultural practices (cropland management, forest to crops, improved grassland management, or rewilding). You can also view which agricultural scenario yields a higher SOC prediction.

- A map view of your average total SOC predictions in tC/ha (tonnes of carbon per hectare) for the year 2038.

Lastly, as with all of our dashboards, you are able to view and download the raw data for your own research.

A Conversation with the National Indian Carbon Coalition

What does SOC planning entail for tribal communities, and how are tribes integrating it into their climate change mitigation efforts? We talked with Bryan VanStippen to better understand the carbon planning situation for tribes.

Bryan serves as the Executive Director for the National Indian Carbon Coalition (NICC), a Native-led nonprofit organization dedicated to helping tribal nations and members protect and preserve their lands through participation in the carbon credit market and other environmental commodities markets. NICC provides education, outreach, and technical assistance to tribes, including helpful resources related to carbon project development, mapping, and more. You can read more about their mission and resources here.

Currently, many tribes in the U.S. are leading innovative carbon projects and reaping the additional benefits that come from combining carbon market participation with their well-established land care activities. Tribes are pursuing carbon projects and credit development on their farmlands, ranchlands, and forest lands, with exciting examples from the Fond du Lac Band, Keeweenaw Bay Indian Community, and Lower Brule.

By gaining access and directly participating in regional or international carbon markets, tribes can generate new revenue streams for their communities while also reducing emissions and maintaining care of their lands. However, as NICC points out, talk of the potential revenue gains should not be the center of the conversation. Carbon planning and market participation is a way for tribes to assert greater stewardship of their lands—preserving their land base for future generations and protecting their traditional resources.

...talk of the potential revenue gains should not be the center of the conversation. Carbon planning and market participation is a way for tribes to assert greater stewardship of their lands—preserving their land base for future generations and protecting their traditional resources.

While the benefits are more straightforward, the complexities of the carbon market and carbon planning process can muddle the vision for some tribes. Most communities are less interested in sorting out the technical jargon and more interested in how this type of planning helps them realize a better future for their tribe.

Along with NLAP’s SOC dashboard, trusted organizations like the NICC provide tribes with the necessary information and management support to determine a particular carbon project’s potential benefits, project options, and partnership opportunities.

As with any decision, tribes reserve the right to pursue or pivot away from activities that involve their communities and homelands. In the wake of a growing carbon market, it is more important than ever to support Native self-determination, cultural preservation, and Native-led sustainable development. Tools like the SOC dashboard help frame the potential impacts on a tribe’s SOC, providing a baseline for tribes to work with as they consider future projects. Additionally, Native-led organizations like the NICC are there for tribes throughout the planning process to ensure that values and tribal land ownership are protected.

Written by Raven McMullin