By Aliyah Keuthan

Edited by Emma Scheerer

This blog is the first of two posts analyzing the challenges Native communities face in accessing clean, sustainable water.

As climate change threatens water supplies globally, it becomes increasingly imperative that indigenous people have the right to access, monitor, and sustainably manage available water resources. Growing conflicts between the water needs of native and non-native communities, including businesses and farms, make it necessary to ensure equitable access to water. The Lakota people of the Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and Lower Brule Sioux reservations have faced challenges in accessing potable water, as well as in obtaining funding for water distribution and treatment systems. The following paragraphs will explore some of these challenges.

The Mni Wiconi Water Pipeline

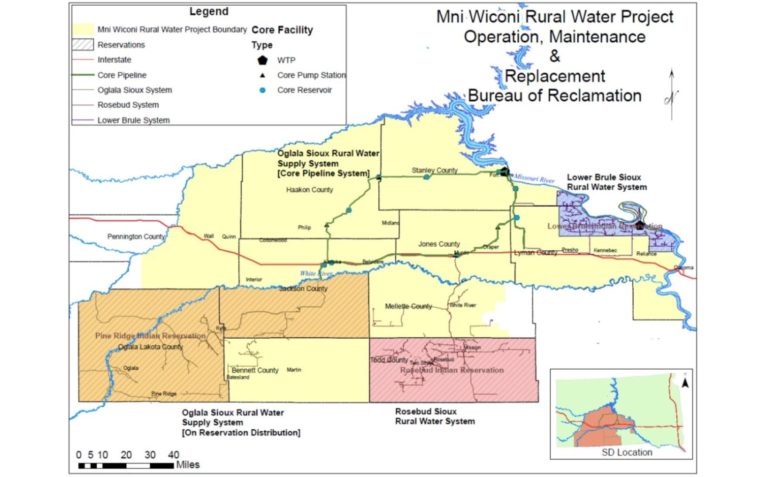

In October of 1988, Congress appropriated funding for the Mni Wiconi (“water of life” in the Lakota language) water pipeline project. The project would be the largest of its kind in the United States; it would provide nine counties and three reservations (Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and Lower Brule) with access to clean water via a 4,500-mile pipeline system from the Missouri River (Tupper, 2019). Prior to consultation with the tribes, this project was supported by off-reservation ranchers who stood to benefit from it. However, federal funding could not be obtained without including the three Indian reservations as primary beneficiaries in the proposed service area.

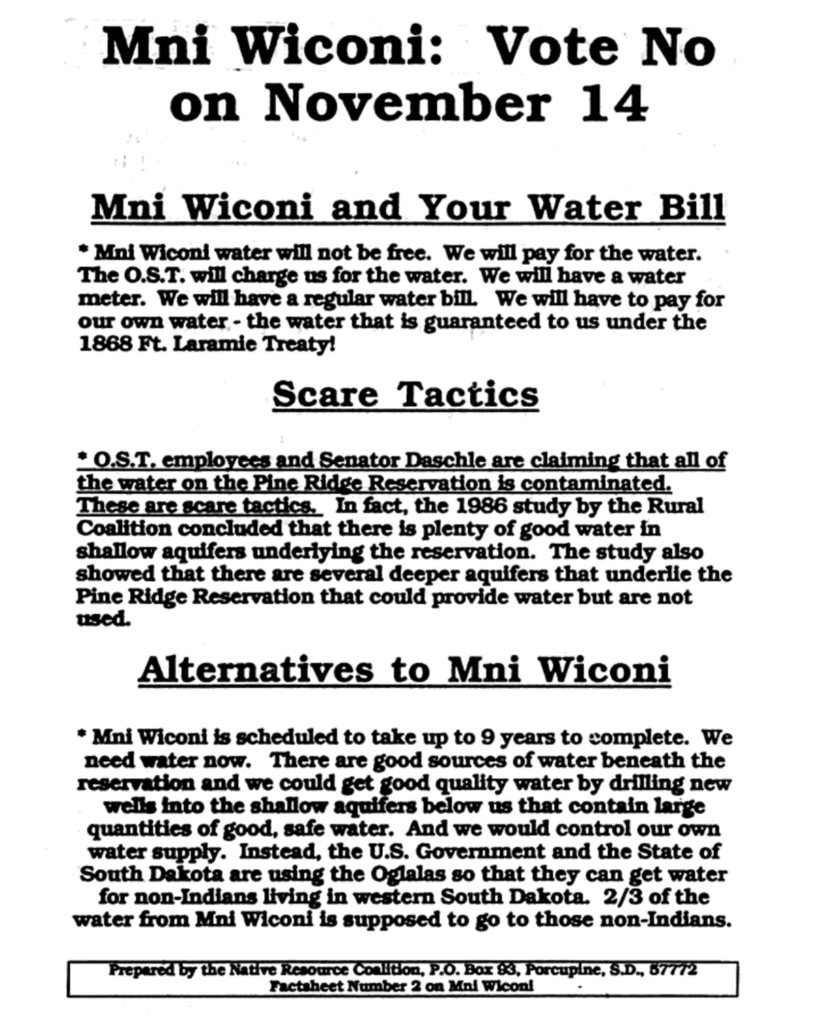

The proposal met immediate disapproval from Sioux tribal members. The following factsheet, originally published by the Native Resource Coalition on the Pine Ridge reservation, states emphatically how displeased tribal members were with the proposed Mni Wiconi House Bill. Documents including the factsheet below were presented as exhibits one through seven in a hearing before the 101st United States Congress House Subcommittee on April 4, 1990, by Cecelia Fire Thunder of the Native Resource Coalition.

Fire Thunder, an Oglala Sioux Tribal member, stated in her testimony that the pipeline was a blatant violation of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which assured perpetual rights to both banks of the Missouri River in the treaty region as compensation for government confiscation of Sioux lands in the Black Hills. Fire Thunder also provided the documented results of a popular referendum vote on November 14, 1989, which struck the proposal down 1,017 to 873 (Energy and Water Development, 1990, p. 2886-88).

She argued that 8,000 non-Indians off-reservation were the primary beneficiaries of the project. She believed the project had been forced through the legislative channels by a non-native minority with farm and ranch interests, namely the Stockgrowers Association, which accounted for over two-thirds of the proposed service area.

Additional testimony revealed that the project excluded the LaCreek district, Red Shirt Village, Batesland, and Wakpamni communities on the Pine Ridge reservation, further straining the tribe’s trust.

Despite the resistance of tribal communities, the final vote supported the creation of the Mni Wiconi Pipeline project. According to Willard Clifford, the current Department Manager of the Oglala Sioux’s rural water system, “the first Missouri River water reached Pine Ridge in 1994” (personal communication, June 27, 2022).

In 2008, the pipeline had still not been completed. John Yellowbird Steele (an Oglala Sioux tribal leader) addressed authorities in Sioux Falls and requested a new amendment which would appropriate funds for completing Mni Wiconi project goals . Steele reminded representatives that Red Cloud’s War, which culminated in the Treaty of 1868 and the Winters Doctrine, was a fight for Sioux water rights and access to both banks of the Missouri River (Water Issues, 2008). His position was recognized and the Mni Wiconi project received more funding—but it still was not enough to complete the pipeline.

In an effort to reduce the cost of the pipeline, water from existing wells on the Pine Ridge reservation was incorporated into the Mni Wiconi system. This well water, which is piped to Mni Wiconi treatment facilities in the towns of Pine Ridge and Kyle, is treated and blended with Missouri River water, which itself is piped in from the treatment facility at Ft. Pierre, South Dakota.

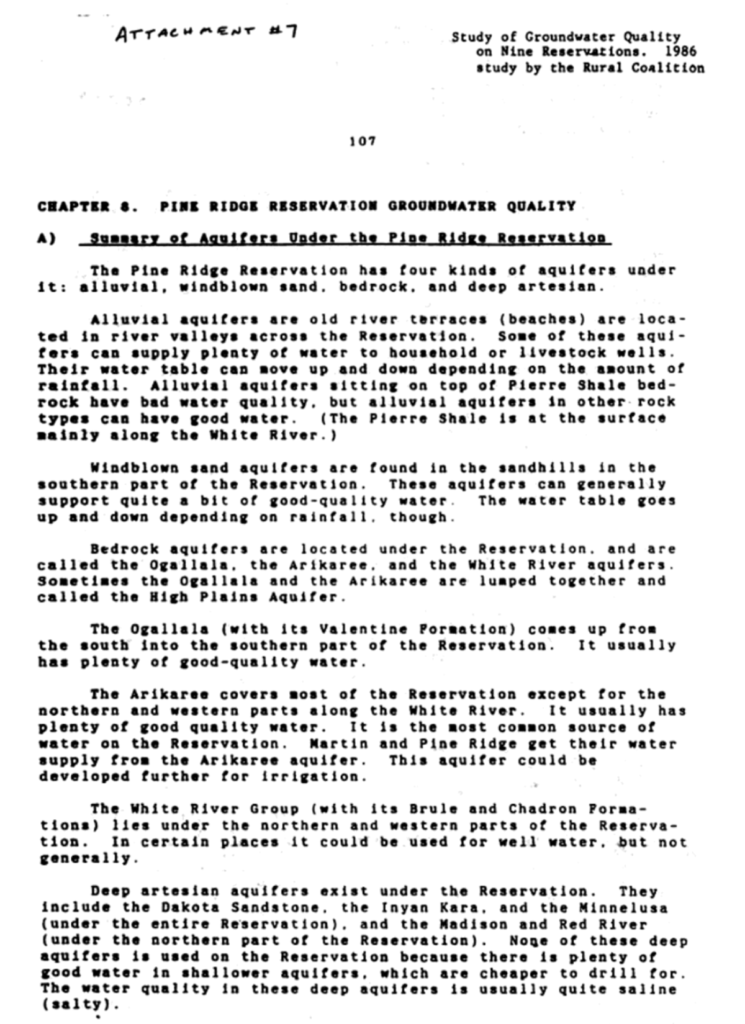

The attachment at right is part of the testimony given by Cecelia Fire Thunder during the hearing on April 4, 1990. It shows a 1986 groundwater quality study of the various aquifers beneath all nine Sioux reservations in South Dakota. This document supported an alternative plan for tapping into existing aquifers under the reservations as a more efficient way for tribes to obtain quality, locally-treated drinking water. This data suggests that sufficient water was available to tribes via numerous groundwater sources on native lands; therefore, it likely would have been more efficient to simply build treatment facilities on the reservations.

Contaminated Surface & Groundwater

Groundwater, including wells, and surface water, such as lakes and streams, are tied to water tables and aquifers (Long & Putnam, 2010, p. 64).

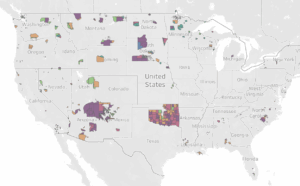

The map below displays the service area of the Mni Wiconi water project; this service area includes ten South Dakotan counties, multiple rivers (such as the Missouri and Cheyenne), and three Sioux reservations (Oglala, Rosebud, and Lower Brule).

Clifford stated that some of the older wells still in use on Pine Ridge were found to be contaminated with uranium and arsenic in excess of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) maximum contaminant level (MCL) of 30 parts per billion (ppb). The University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee’s chemistry department analyzed samples from over 200 Pine Ridge wells; results showed Uranium-238 levels as high as 60ppb in some surface water samples and 40ppb in some groundwater samples (Botzum et al., 2011).

Both surface water and groundwater contaminated with radioactive particles cannot be reclaimed. Wells found with Uranium-238 levels above the EPA MCL of 30ppb can no longer be used for drinking water and must be sealed. These wells cannot be used in the Mni Wiconi system and are not suitable for any purpose.

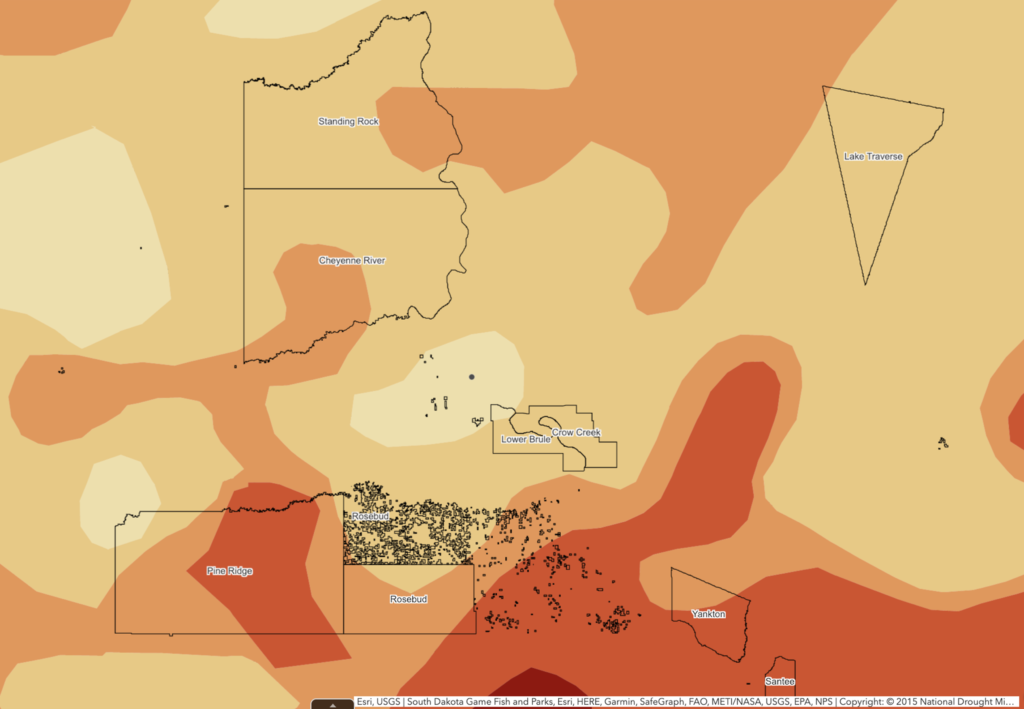

Contaminants in surface water are hard to contain and can seep into aquifers with precipitation. In times of drought, particulates become more concentrated, causing contaminant levels to rise in both ground and surface water resources, which can result in the closure of even more wells. This puts even more stress on uncontaminated aquifers, wells, and rivers as more people rely on fewer clean water sources.

Contaminants can enter surface and groundwater through many practices, some of which will be discussed below in more detail.

Irrigation & Agriculture

In 2015, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimated that 73.2 billion gallons of freshwater were used per day for irrigation in the United States (Dieter et al., 2018). This water was composed of both withdrawals (water withdrawn from ground or surface water sources) and reclaimed wastewater.

In South Dakota specifically, a 2005 report documented that approximately 501 million gallons of water were being withdrawn per day—or more specifically, 271 million gallons of water per day were withdrawn from groundwater, while about 230 million gallons per day were withdrawn from surface water sources (Carter & Neitzert, 2008). About 58 percent of this water was used for irrigation, while public use (which includes domestic water usage) accounted for about 20 percent of these withdrawals. These numbers clearly demonstrate that irrigation practices are the largest consumer of water in South Dakota.

Irrigation is a very common practice in agriculture. According to the United States Department of Agriculture’s data from 2017, on the Pine Ridge reservation, the amount of cropland harvested by non-natives far exceeds the amount of cropland harvested by native farmers, even though non-natives lease or own only about a fourth of the total farm acreage on native lands (NLIS, 2021). On South Dakota reservations, non-natives operate about 94% of the irrigated cropland, or 35,326 acres, whereas native farmers operate about 6% of irrigated cropland, a total of 2,256 acres. The Native Lands Advocacy Project illustrates these differences through our Agriculture on Native Lands data dashboard, shown below.

These non-native farms, which are on native reservation lands and make up the vast majority of irrigated cropland in South Dakota’s Indian Country, use ground and surface water resources that could be used for the crops of native farmers or domestic usage by tribal members. Because of their disproportionate control of irrigated croplands, non-native farmers compete with the tribes’ internal municipal and agricultural needs, which will invariably cause conflict as severe drought becomes more common due to climate change.

In the map of South Dakota at left, retrieved from the Native Lands Advocacy Project’s Drought Monitor Map (2022), the colors represent a range of drought conditions, classified according to the U.S. Drought Monitor: from light yellow, which represents areas that are abnormally dry, to deep red, which represents exceptional drought. This map confirms that drought is an already-present issue for residents of South Dakota, not a distant threat.

The conventional farming practices used by most non-native farmers on native lands do not reflect efficient resource management. Water use for irrigation is not the only problem. Intensive farming methods practiced by most non-native farmers include the use of commercial pesticides and fertilizers (Red Lodge, 2021). Runoff from agricultural waste flushes these harmful chemical fertilizers and pesticides into surface water, which then leeches into groundwater, further exacerbating clean water goals for Lakota communities.

Outdated & Incomplete Infrastructure

Over the span of two decades (and ending in 2013), several amendments which allocated federal funding for Mni Wiconi were passed in an attempt to make good on the project’s stated purpose: to pipe clean, treated Missouri River water to native communities in the Mni Wiconi service area (Tupper, 2019). Gradually, outdated infrastructure was replaced—an ongoing task, according to Ernest Abold at Oglala Sioux Tribe (OST) Rural Water and Sewage in the town of Pine Ridge. Abold stated that “unless it breaks, the old pipes stay in use” (personal communication, June 26, 2022). According to a report by Seth Tupper of the Guardian (2019), some of the older pipes in the system were made with asbestos cement, and due to the slow process of replacing old infrastructure, concerns have arisen that some of those pipes might still be in use.

In addition to updating water delivery systems, outdated waste water and sewage treatment systems also needed to be replaced. According to the South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), acquiring funds to replace outdated sewage treatment systems, especially for communities of 3,500 or less, is difficult because of high costs and a small tax base. In 2018, the State Water Plan, which facilitates projects like Mni Wiconi and their funding, identified 36 unfunded wastewater projects in South Dakota, which would cost $157 million to address. DENR receives only a third of its funding from the federal government, a quarter from the state, and 40 percent from fees—this means that the burden of paying for projects like Mni Wiconi falls largely on the shoulders of those who need them most (Pfankuch, 2018).

As the last reserves of Mni Wiconi funds trickled away, many people on tribal lands still hauled water in water buffalos (large plastic barrels or tanks for hauling and storing water) from safe water supplies ten or more miles away from their homes, a difficult task that became almost impossible in snowy winter months (Tupper, 2019).

To counter poverty-related lack of access to water, Martin Indian Health Services (IHS) Office of Environmental Health and Engineering has provided well-drilling services for hundreds of Lakota households since the 1980s.

In the end, native communities had to wait for funding for clean water from the Mni Wiconi project to trickle down to them—funds which ironically would not have been approved had native communities not been the intended recipients of the Mni Wiconi project; funds which should have been allocated in a manner that prioritized the needs of native communities.

Ongoing Needs

In 2019, severe flooding engulfed parts of South Dakota, compromising groundwater sources and leaving residents, including many on the Pine Ridge, Lower Brule, and Rosebud reservations, unable to access uncontaminated water. The National Guard delivered truckloads of bottled water and sanitation supplies, but could not reach residents in remote areas on tribal lands. The National Peace Corps Association and other water charities provided 310 portable water filtration system kits to 2,000 isolated residents, a sustainable solution that could be used repeatedly over multiple water disasters (NPCA, 2019).

In March of 2022, the EPA, which handles wastewater permitting for tribes, updated its online list of grants, low-interest loans, and technical support available to tribes from federal agencies under the Federal Infrastructure Task Force. Resources exist specifically for tribes to establish, replace, or repair water treatment infrastructure (USEPA, 2022). Also in 2022, the South Dakota Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources (DANR) announced their approval of $73,634,334 in grants and $25,069,286 in low-interest loans for drinking water, wastewater, and solid waste treatment facilities in several South Dakota communities, but none of these included tribal lands (Walsh, 2022).

This data indicates that there are still occupied housing units with incomplete plumbing systems, the greatest number and percentage of which are on the Pine Ridge reservation at 5.1 to 8.1 percent. This further indicates a potential lack of access to potable, uncontaminated water for a significant portion of the total population—not just a handful of isolated individuals in remote areas.

In areas like the northernmost reaches of Pine Ridge, dangers increase when using contaminated water because of the alkalinity of the water. Here, high alkalinity mobilizes uranium-238 more greatly than in areas with lower alkalinity (Swift Bird et al., 2020).

The presence of unsafe levels of toxicity in groundwater has serious health implications. Some wells may not be monitored for use or tested for impurities on a regular basis, if at all. Native populations experience high rates of cancer, kidney disease, and other health problems that arise from exposure to toxins in water. However, Clifford stated that Mni Wiconi water is carefully monitored to keep the system compliant with federal standards for drinking water.

References

Botzum, C. J., Ejnik, J. W., Converse, K., LaGarry, H. E., Bhattacharyya, P. (October 9, 2011). Uranium contamination in drinking water in the Pine Ridge Reservation. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, 43(5), 125. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312521024_CONFERENCE_PAPER_Uranium_contamination_in_drinking_water_in_the_Pine_Ridge_Reservation_southwestern_South_Dakota

Carter, J. M., Neitzert, K. M. (December 28, 2008). Estimated use of water in South Dakota, 2005. (Report No. 2008-5216). USGS South Dakota Water Science Center. https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20085216

Chesnais, A. (2022). Complete Plumbing, AIANNHCE. (Ed., Bartecchi, D., July 23, 2022).

Dieter, C. A., Maupin, M. A., Caldwell, R. R., Harris, M. A., Ivahnenko, T. I., Lovelace, J. K., Barber, N. L., & Linsey, K. S. (June 19, 2018). Estimated use of water in the United States in 2015. (Report No. 1441). United States Geological Survey. http://www.usgs.gov/publications/estimated-use-water-united-states-2015

Energy and water development appropriations for 1991: Hearings before a subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives, 101st Cong. 2 (1990) (testimony of Cecelia Fire Thunder). Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books/about/Energy_and_water_development_appropriati.html?id=k7CvXxweKqYC#v=snippet&q=mni%20wiconi%20water%20project&f=false

Long, A.J., Putnam, L.D. (2010). Simulated Groundwater Flow in the Ogallala and Arikaree Aquifers, Rosebud Indian Reservation Area, South Dakota—Revisions with Data Through Water Year 2008 and Simulations of Potential Future Scenarios. (Report No. 2010–5105). U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations. https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2010/5105/pdf/sir10-5105.pdf

National Peace Corps Association (May 13, 2019). Water crisis on Sioux Reservations. https://www.peacecorpsconnect.org/articles/water-crisis-on-sioux-reservations

Native Lands Advocacy Project. (2022, May). U.S. Drought Monitor for Native Lands. Native Land Information System. https://nativeland.info/blog/thematic-maps/drought-on-us-native-lands/

Native Land Information System (2021). Irrigated land (acres) by race on Cheyenne River Sioux, Crow Creek Sioux, Lower Brule and 6 more reservation(s) in 2017. https://public.tableau.com/shared/4554SCZ6J?:display_count=n&:origin=viz_share_link&:embed=y

Pfankuch, B. (September 5, 2018). Upgrading wastewater systems a $160 million task in South Dakota. South Dakota News Watch. https://www.sdnewswatch.org/stories/upgrading-wastewater-systems-a-160-million-task-in-s-d/

Pfankuch, B. (September 11, 2018). Should South Dakota farmers be forced to improve pollution control methods? South Dakota News Watch. https://www.sdnewswatch.org/stories/should-farmers-be-forced-to-improve-pollution-control-methods/

Red Lodge, E. (2021, December 21). Use of Chemicals for Croplands on Native Lands by Non-Natives Considerably More Than Use by Natives. Native Land Information System. https://nativeland.info/blog/topics/native-agriculture-land-use/use-of-chemicals-for-croplands-on-native-lands-by-non-natives-considerably-more-than-use-by-natives/

Running Strong for American Indian Youth (2019). Increasing access to clean water on Pine Ridge. https://indianyouth.org/increasing-access-to-clean-water-on-pine-ridge/

Running Strong for American Indian Youth (2021). Organic gardens and food. https://indianyouth.org/what-we-do/our-programs/organic-gardens-food/

Running Strong for American Indian Youth (2021). Slim Buttes Agricultural Project continues to “ground” Pine Ridge families to sources of life. https://indianyouth.org/slim-buttes-agricultural-project-continues-to-ground-pine-ridge-families-to-sources-of-life/

South Dakota Public Broadcasting (October 18, 2021). Repairs cause water restrictions for Mni Wiconi system. SDPB Radio. https://listen.sdpb.org/business-economics/2021-10-18/repairs-cause-water-restrictions-for-mni-wiconi-system

Swift Bird, K., Navarre-Sitchler, A., Singha, K. (2020). Hydrogeological controls of arsenic and uranium dissolution into groundwater of the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota. Applied Geochemistry 114 (2020) 104522. https://people.mines.edu/ksingha/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2021/03/swiftbird_etal2020.pdf

Tupper, S. (May 23, 2019). A promise unfulfilled: Water pipeline stops short for Sioux reservation. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/23/a-promise-unfulfilled-water-pipeline-stop-short-for-sioux-reservation

United States Environmental Protection Agency (March 8, 2022). Federal Water and Wastewater Resources for Tribes. https://www.epa.gov/tribaldrinkingwater/federal-water-and-wastewater-resources-tribes

Walsh, B. (May 17, 2022). DANR Announces More Than $98 Million for South Dakota Environmental Projects. South Dakota State News. https://news.sd.gov/newsitem.aspx?id=30227

Water Issues in the Great Plains: Hearing before the subcommittee on water and power, Senate, 110th Cong. 2 (2008) (testimony of John Yellowbird Steele). Retrieved from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-110shrg44663/html/CHRG-110shrg44663.htm

Images:

City of Fort Collins, CO. (2014). Drake Water Reclamation Facility Tour [Photograph]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/fortcollinsgov/14560510074/in/photostream/. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

South Dakota Public Broadcasting (2021). Mni Wiconi Rural Water Project Operation, Maintenance, & Replacement [Online Map]. https://listen.sdpb.org/business-economics/2021-10-18/repairs-cause-water-restrictions-for-mni-wiconi-system

Silk, N., Robbins, E. (March 2, 2021). Standing Stronger Together [Photograph]. River Network. https://www.rivernetwork.org/standing-stronger-together-ngos-tribes-and-water/

Interviews:

E. Abold, personal communication, June 26, 2022.

W. Clifford, personal communication, June 27, 2022.