By Aude K. Chesnais

“At a time where climate planning becomes urgent and global attention is increasing on the ecological value of land, Native Peoples’ land stewardship practices may well gain in recognition, which could strengthen tribal sovereignty in the US”

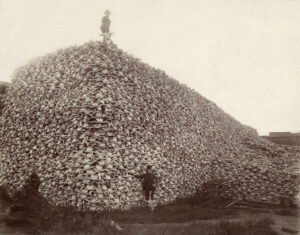

Today, Indigenous peoples manage 80% of the world’s biodiversity, yet they receive only 0.74% of climate funding to support them in that task (Rainforest Foundation Norway, 2020) Not only that, their voices are largely excluded from the climate debate, a theme consistent with the long history of erasure of Indigenous peoples’ voices, and data colonialism where information about Indigenous lands is missing, mishandled and misrepresented.

However, at a time where climate planning becomes urgent and global attention is increasingly shifting away from carbon markets and carbon scrubbing tech towards the ability of ecosystems to naturally sequester carbon, indigenous peoples’ land and stewardship practices are gaining increasing attention as the desired path forward. In an attempt to identify these areas of high importance, an international consortium developed a framework known as Key Biodiversity Areas or KBAs. Here, I explore the possible usefulness and uses of KBAs data for Tribal land climate planning and stewardship.

While peoples are not equally responsible for climate change, it is a global issue which requires international collaboration, and tribes in the US have a key role to play. The Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework is a UN initiative which gathers most countries in the world to address the issue of biodiversity loss. It was not ratified by the US, as many environmental agreements, but is considered a key framework to address climate change. It advocates for 30% of terrestrial land, inland water and oceans to be protected by 2030.

Currently in the US, 12% of land is protected (2020 numbers), mostly thanks to national and state parks; an actual down by 2% since 2019. Protected Areas form some legal protection around “a clearly defined geographical space, recognized, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values” (IUCN). Prior to protecting areas comes the task to recognize areas that need to be protected. These areas are becoming increasingly known worldwide as Key Biodiversity Areas or KBAs. “Many entities are already using the KBA data – some on a daily basis – to influence their decisions. And this use is expanding rapidly” (keybiodiversityareas.org). The KBA data is also a useful indicator for several of the UN 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) towards a healthier planet.

In response to the urgent need for worldwide consolidated datasets to plan for land conservation and biodiversity, the IBAT portal gathers three evolutive datasets for 1) Protected Areas, 2) Key Biodiversity Areas and 3) the Red List for endangered species. Modeled after satellite imagery and bird habitats estimates, KBAs have grown to include diverse criteria, summarized by the recent IUCN publication to try and set a standard for the global community.

Criteria focus on:

- Threatened Biodiversity

- Geographically restricted biodiversity

- Ecological Integrity

- Biological Processes

- Irreplaceability through quantitative analysis

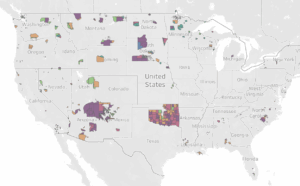

According to the KBA site, Indigenous Peoples and Local Community (IPLC) are recognized as major stakeholders in the management of KBAs. KBA criteria include a provisional “inclusion of a wide range of data sources: for example, drawing from traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and indigenous knowledge (IP) as appropriate.” However, the data is not currently released with clear variables to recognize whether identified KBAs are related to TEK or Native stewardship. In fact, KBA criteria are currently not differentiated in the database, which might be problematic because some criteria assess the ecological importance of areas for biodiversity, while others are about identified scarcity. Nevertheless, comparing KBAs with Native Lands shows some interesting results that could support Native Peoples’ stewardship and their key role in sustainably managing land in the US.

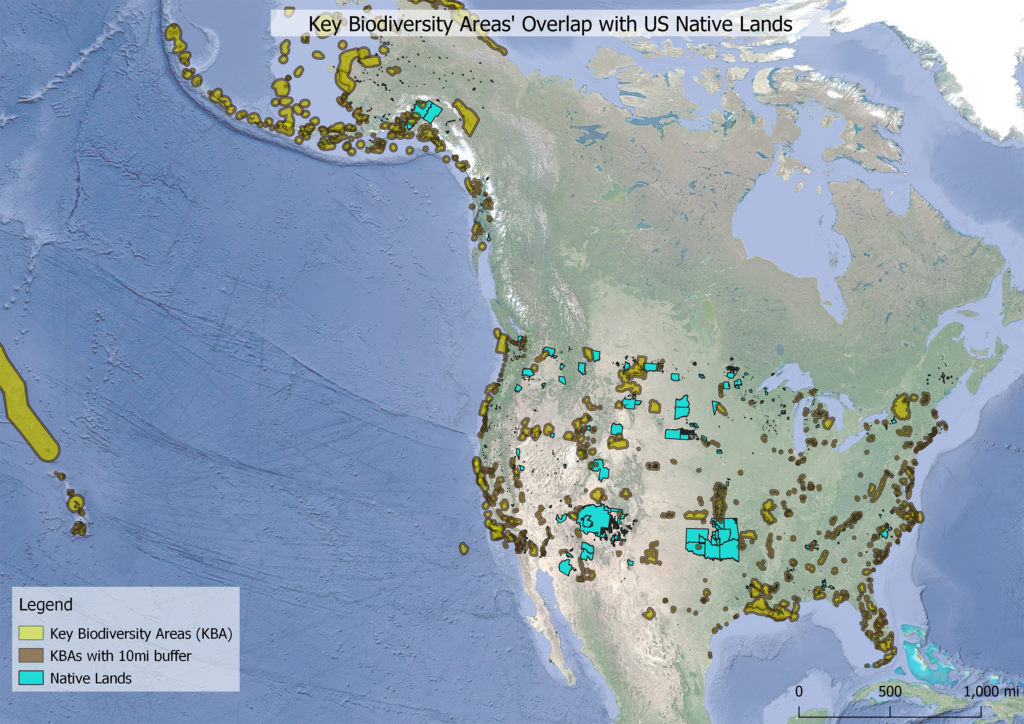

While tribal lands make up 2.6% of the United States, they overlap with 12% of KBAs at least once (sometimes several tribes overlap with the same KBA). Even more significantly, when applying a 10 mile buffer around KBAs, the number increases to 17.4% of KBAs within 10 mile of a reservation, 22.6% of reservations within 10 mile of a KBA and 5.41% actual land area overlap between reservations and KBAs. In short, this new ground-breaking analysis confirms that KBAs are located close to reservations!

The reason WHY is the fundamental question here! An hypothesis could be that areas around tribal geographies are less prone to industrialization. A recent article by Farrell et. al, (2021) that compares historical to present-day native land base opportunities to assess the effect of land dispossession on Native Peoples. They found that: “migration patterns may have resulted in tribes being moved to areas that were geographically rural, “unsettled,” and perceived to be of less economic value.” Because industrialization often holds a reverse relationship with biodiversity, these areas might potentially be of more ecological values.

But the proximity of KBAs to tribes could also be due to more conservative land-use on reservations that are impacting a wider area. Ecosystems can hardly be seen as silos, and they are heavily impacted by intra-regional dynamics. One way to figure it out would be to have access to the criteria used for classifying them as KBA within the database. Indeed, closeness to a KBA defined by a criterion for Intact biodiversity would mean a very different result than if it was defined by the prevalence of Endangered species. This calls for more transparency in the KBA public database. However, with our own Intact Habitat Layer, the NLAP might soon be able to refine these hypotheses.

Although KBA data is very useful and promising to support tribal conservation efforts and climate planning, it should be pondered against other data, and also requires more inclusion of Native Peoples in the definition and selection of KBAs. Tribes could also submit their own KBAs to enrich the database, gain visibility for their efforts and/or recognize land they know to be of ecological importance. And KBAs would also improve with more input of TEK. Another area for improvement in the IBAT database would be to work on inclusion of Indigenous Peoples in the Protected Areas Layer. Indeed, this layer does not rely on satellite imagery and modeling but rather from national agencies’ reports to the international Protected Areas Database (PAD). As a result, the layer does not include to date any Tribal Protected Areas in the United States. Is it due to a lack of reporting? Governance or data sensitivity issues?

Improvement of the PAD data is key for conservation because it goes hand in hand with KBAs. Monitoring conservation requires defining KBAs and comparing them to areas that are efficiently being protected (PAD). One subset of PAD called Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs), may be particularly appropriate to recognize the positive impact of Native Land stewardship.

More research is coming in this topic, as we are developing a dedicated dashboard to further investigate the relationship between conservation potential and trends in US Native Land. Keep tuned in!

References

Farrell, A. J., Mcconnell, K., Burow, P. B., Bayham, J., & Whyte, K. (2021). Effects of land dispossession and forced migration on Indigenous peoples in North America. Science, 374(6567).

IUCN. (2016). A global standard for the identification of Key Biodiversity Areas. Retrieved from www.chadiabi.com

KBA.org. “How KBAs are used”. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from http://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/about-kbas/applications

Rainforest Foundation Norway. (2020). Falling Short. Retrieved from https://d5i6is0eze552.cloudfront.net/documents/Publikasjoner/Andre-rapporter/RFN_Falling_short_2021.pdf?mtime=20210412123104

Reclaiming Native Truth Project. (2018). Reclaiming Native Truth: Research findings: Compilation of all research. Retrieved from https://www.reclaimingnativetruth.com/

Rodriguez-Lonebear, D. (2016). Building a data revolution in Indian country. In Indigenous data sovereignty: towards an agenda (pp. 253–274). oapen.org. Retrieved from http://www.oapen.org/download?type=document&docid=624262#page=277