If you do a quick Google search of food access on Native American reservations, odds are that you will find a plethora of articles that summarize the reservation food narrative using the following keywords: “food desert,” “food insecurity,” and “food poverty.” Although recognizing this reality is important –and the necessary first step to securing federal and state resources to mitigate the lack of food access on reservations– discussing tribes’ relationships to food only in terms of “food desert” ignores and conceals present efforts to restore Native food resilience, healthy, and security.

Discussing tribes’ relationships to food only in terms of “food desert” ignores and conceals present efforts to restore Native food health and security.

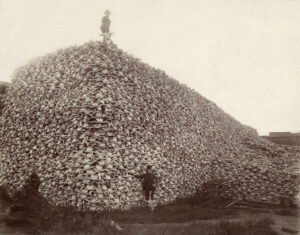

As many in Indian Country know, colonial expansion and the forced removal and relocation of Native peoples disrupted Native food relationships and violently severed Native communities from critical food resources. Since this onslaught on Native food and land systems by settlers, Native Nations have relentlessly fought for their rights and consistently found ways to preserve ancestral foodways, leading to the greater food sovereignty and recovery movement we see today. However, if Native communities have been doing this recovery work for years, why do we not see these efforts equally reflected in the media or national datasets?

NLAP’s Good Food Access Indicator (GFAI) helps Native communities challenge those who look at Native food systems through a deficit lens by creating a new way to measure food access on the reservation. The GFAI also gives Native communities a way to assess and challenge the problematic data gaps in national food access datasets.

Native Food Resilience: A Problem and a Proposal

The popular datasets used to assess the quality of food, access to food, and food production come from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and these include the USDA Food Environment Atlas and the USDA National-Local Food Directories (which also include national self-reported lists for local food hubs and community-supported agriculture).

Although these national datasets provide a helpful baseline for many communities in the U.S., they have inherent limitations when it comes to assessing the Native food movement on reservations:

- National datasets that account for food security are county-based and do not provide information for the specific boundaries of reservations.

- National datasets do not fully account for local and community-based food initiatives. For example, the data made available through the USDA Food Environment Atlas primarily focuses on commodified food and large food retailers. The exclusion of local initiatives makes it hard to accurately assess the successes made in Native food resilience movements across Indian Country.

- National datasets do not provide comprehensive information on the nutritional quality of the food that is made available.

- National datasets focus on negative measures that further marginalize the local food resilience of Native communities.

Therefore, to provide a step forward in challenging how we measure food quality and availability on reservations, NLAP proposed and created the Good Food Access Indicator (GFAI) in 2020 using the same data from the USDA, although a few data limitations persist.

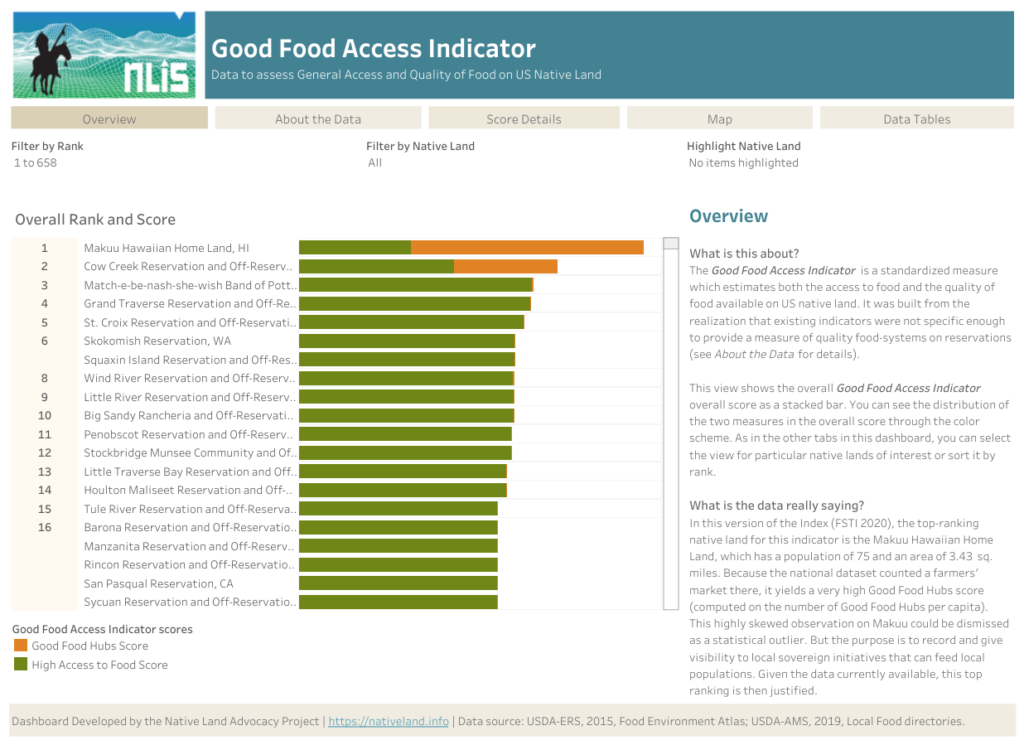

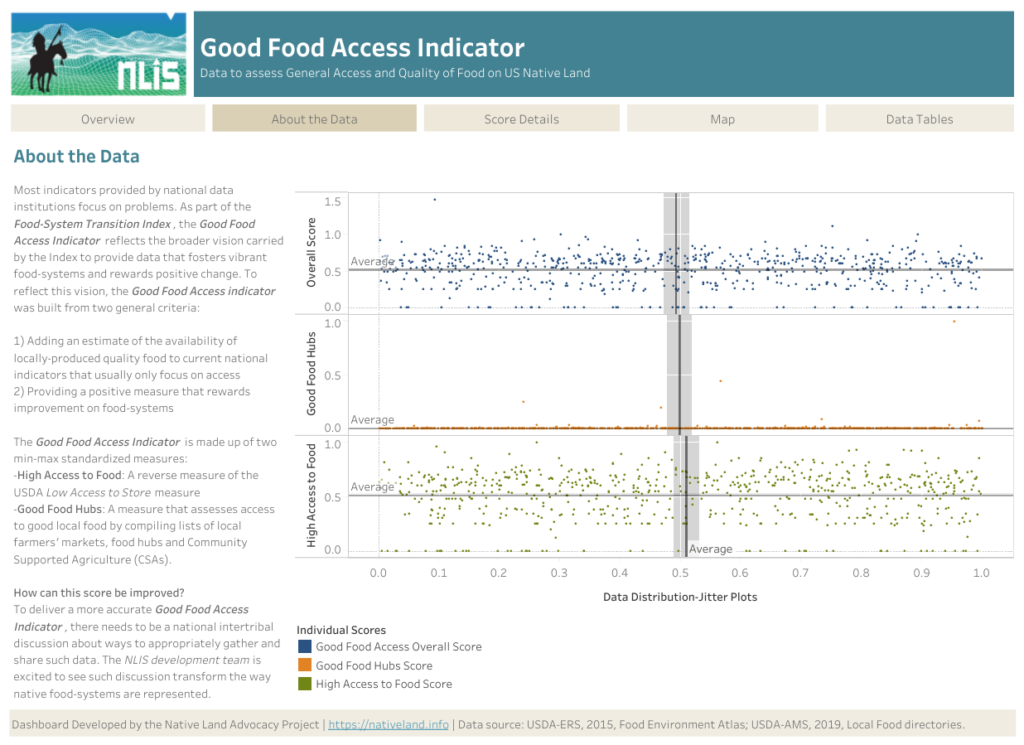

Unlike the typical approach to assessing food access in Native communities, the GFAI presents food access and food quality on Native lands using the overall composite score (range [0;2]) of two normalized* measures:

- High Access to Food: the reverse score of the USDA Low Access to Stores score, usually used as the base measure for identifying food deserts, sourced from the USDA Food Environment Atlas

- Good Food Hubs: our own unique measure that gathers geocoded lists of food markets, local food hubs, and community-supported agriculture (CSAs), sourced from the USDA Local Food Directories

Using these measures allows us to estimate Native food access from a place of abundance rather than lack. For example, instead of presenting food access data according to the USDA Low Access to Stores score, the Good Food Access indicator uses a reversed score to change it into a High Access to Stores score to focus on incremental food access on Native reservations. We combine this score with our measure of Good Food Hubs; a combined estimate of food markets, local food hubs, and CSAs, to add a measure of the quality of food and the strength of local food-systems to our overall indicator.

These small transformations of the data should not lead us to ignore the present needs and challenges that tribes face but rather encourage us to remember tribal progress in rebuilding precious food systems.

Read more about the data sources, transformations, and composite score on our GFAI dashboard page here. To get started, click through the slideshow below, which takes you through the different dashboard tabs and how to use them.

'Overview' Tab

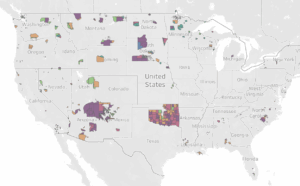

The 'Overview' tab allows you to view the overall rank and Good Food Access score for your reservation. Ranks are based on overall Good Food Access score and range from 1 to 733. You can filter the data by Native land or by rank. Be sure to check out the bottom toolbar for the ability to download, save, and share images of the dashboard!

'About the Data' Tab

This tab allows you to read more about the data sources utilized for the GFAI.

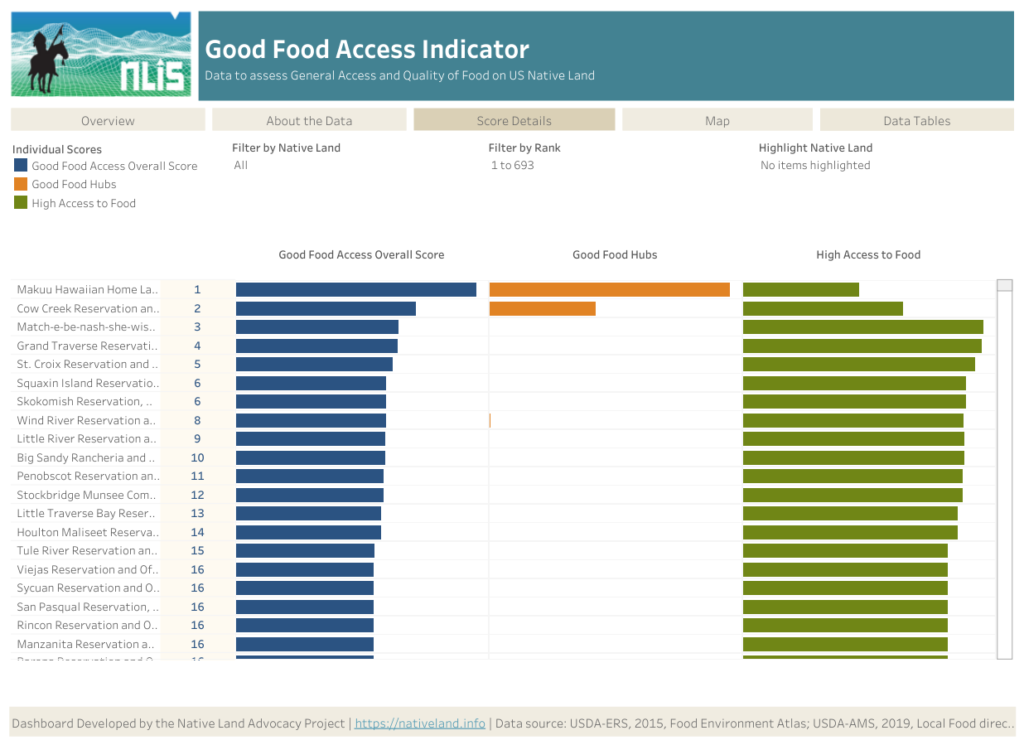

'Score Details' Tab

View the individual scores details for your reservation (instead of the overall rank). View the Good Food Access Overall score, Good Food Hub score, and High Access to Food score. You can filter by rank and by Native land.

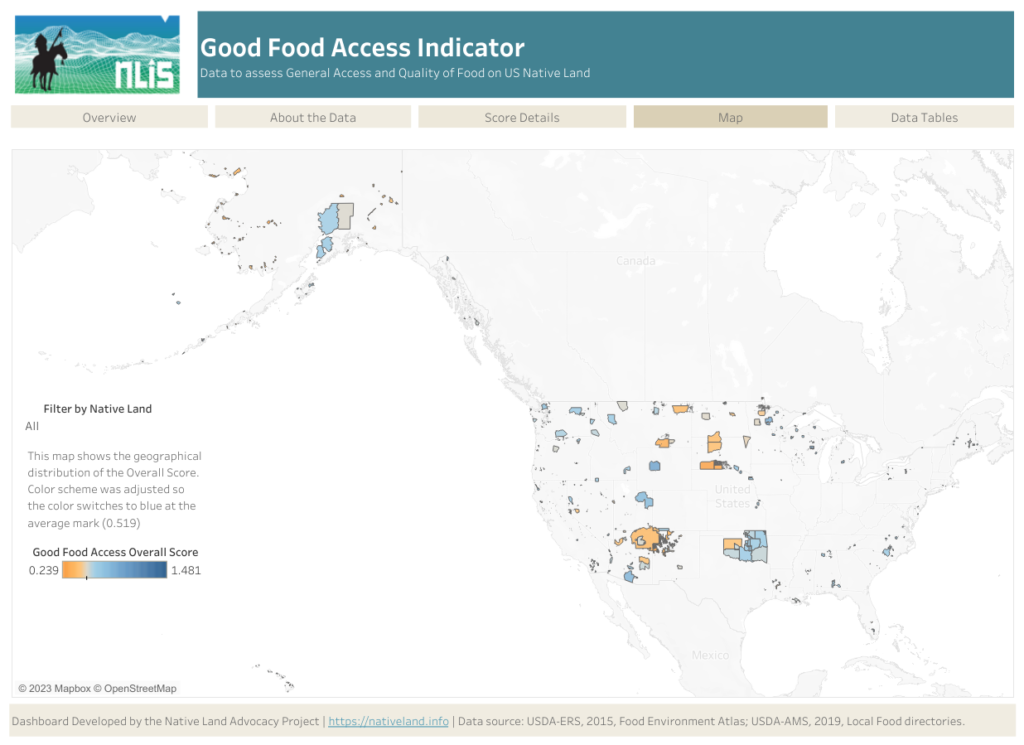

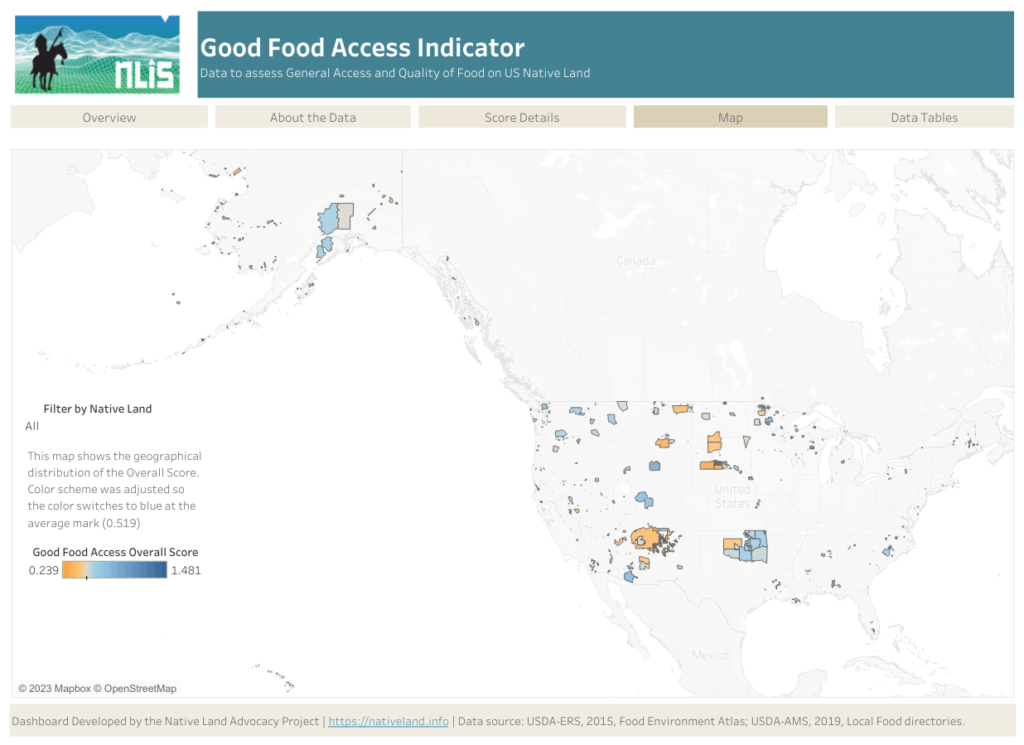

'Map' Tab

View scores and comparisons on a map of Native lands. You have the ability to zoom in/out and filter by reservation.

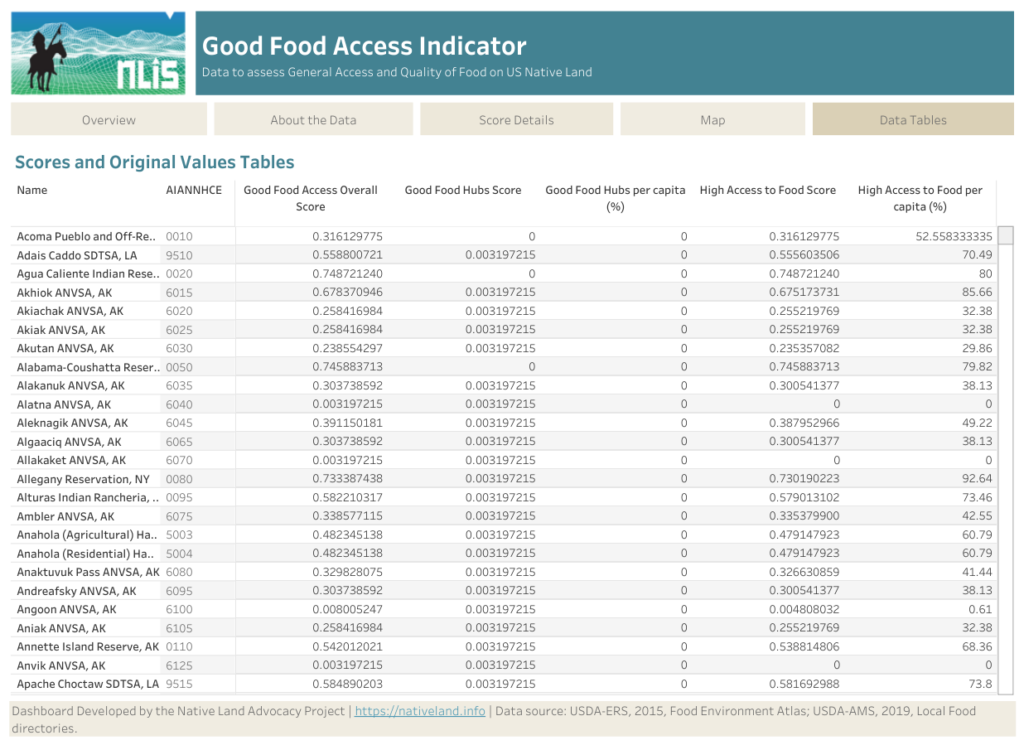

'Data Tables' Tab

This tab allows you to view the raw data tables and score assessments for each reservation. Although this tab does not have a 'filter' feature, you are still able to click on any row and choose to 'Exclude' or 'Keep' any row of data.

A ‘Good Food’ Work in Progress

Due to the availability and nature of the food access data, the GFAI is only as good as the publicly available national datasets it compiles. As previously mentioned, the data used to create the GFAI is limited mainly in its focus on commodified foods/large food retailers and exclusion of most local, Native food initiatives. While the USDA lists of food hubs, markets, and CSAs provide some information, they rely on self-reported data, which is far from being comprehensive. Arguably, tribes and tribal members not reporting to these lists can also be seen as an expression of tribal sovereignty.

Although these limitations create issues in the overall representativeness of the data [...] they reflect NLAP’s conviction that Native communities reserve the right to control the national food narrative for their lands and people.

Although these limitations create issues in the overall representativeness of the data, which limits the quality of the GFAI, they reflect NLAP’s conviction that Native communities reserve the right to control the national food narrative for their lands and people. Thus, we think of the GFAI as a good work in progress that aims to challenge the conversation around data access for Native food planning, and we hope to refine this tool for greater accuracy upon feedback from Native communities. We also encourage the Native communities who identify errors or data gaps in the GFAI to inform the USDA of their existing food initiatives if they desire these national datasets to be more representative of their communities. Moreover, these additions and corrections to USDA’s dataset will also help enrich the current source for the GFAI and make the tool even more usable by tribes.

While having reliable sources of information for tribal food systems is very important, this issue also illustrates some important questions: Who is most legitimate to collect and use tribal information? If not the USDA, then how can tribes create more comprehensive sovereign repositories that truly support their food systems?

Written by Raven McMullin