Between 2012 and 2017, bison numbers have significantly increased on Native lands. What factors have contributed to this major increase, and how does this fit within the larger historical context of American bison? Read on for our reflections on these trends!

What is happening to bison in the United States?

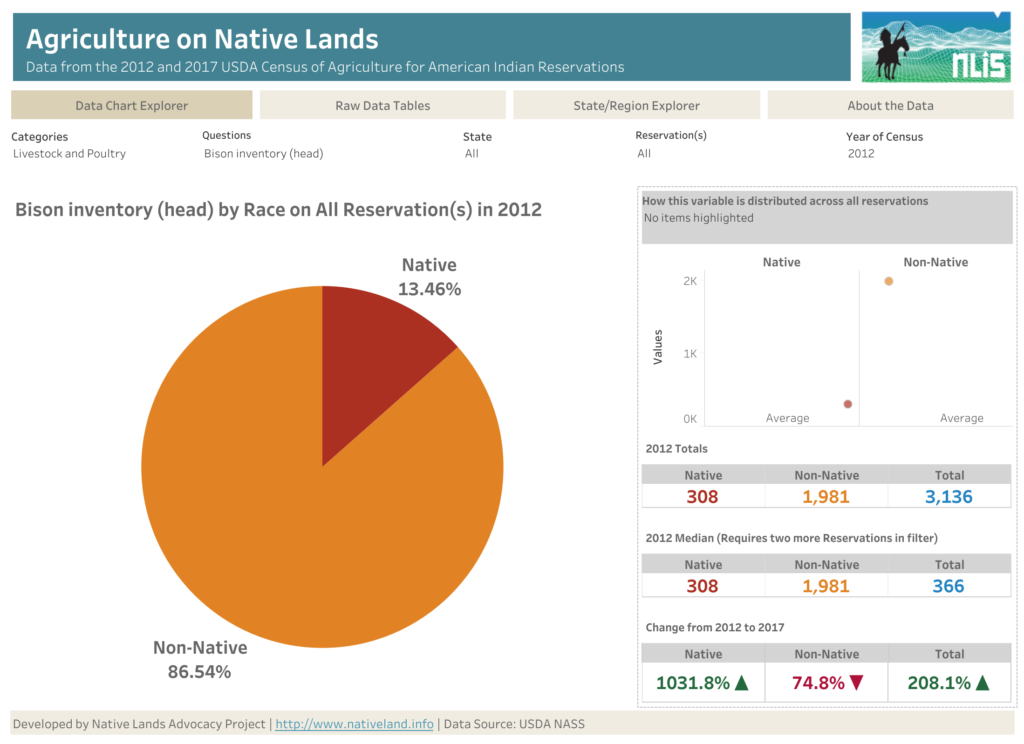

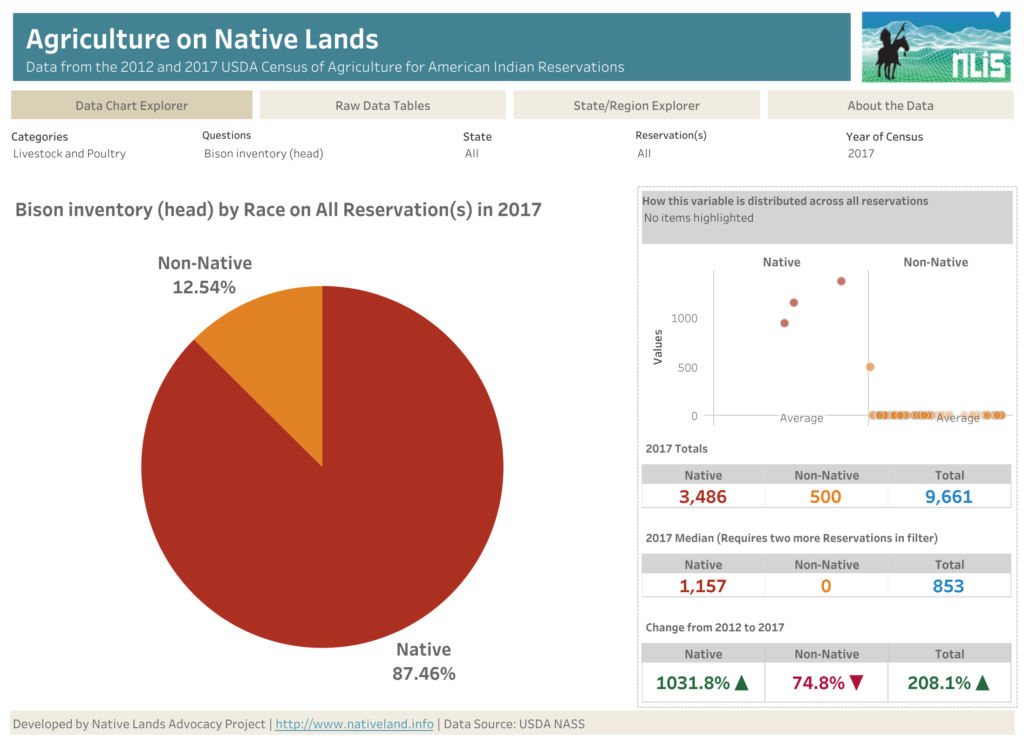

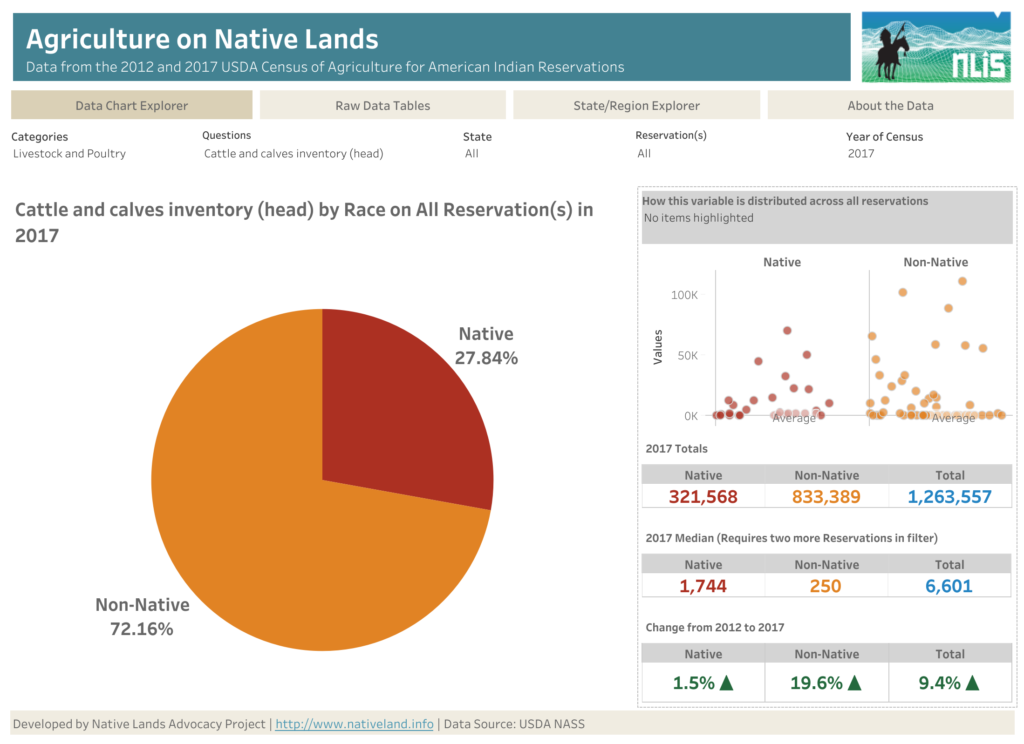

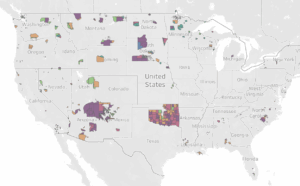

According to the USDA’s Census of Agriculture for American Indian Reservations, bison numbers increased an incredible 1031% on Native lands between 2012 and 2017. This far outpaces the national increase in number of bison, which was 13.36%. See the images below, which present data from the Native Lands Advocacy Project (NLAP)’s dedicated data dashboard for the Census. This dashboard makes it easy for users to explore the data on their own reservations and across Indian Country.

The USDA Census of Agriculture for American Indian Reservations is self-reported and does not contain data for every federally recognized tribe in the United States (read NLAP’s comments on these data limitations here). Therefore, it’s useful as an indicator of trends rather than as a comprehensive accounting of agricultural activities across Indian Country. Nevertheless, this over ten-fold increase, from 308 to 3486 heads of bison on Native-operated farms in the span of five years, is a trend worth highlighting and celebrating.

The destruction of the great bison herds in North America were instrumental to the colonization of Native peoples and their lands, and their resurgence in recent years signals the rise of Native communities’ sovereignty and restoration of the centuries-old relationship between Native peoples and the bison.

History: the planned extinction of the American bison

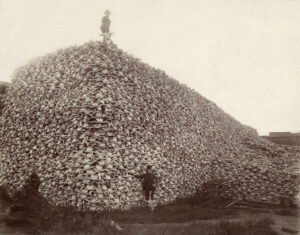

In the 1500s, the wild bison population was estimated as being between 30-60 million heads. From 1830-1889, the active extermination of wild bison species by settlers and the U.S. government took these numbers down to just a few hundred heads. This animation shows the decrease of bison over time.

According to David D. Smits (1994), “scholars of Western American history have long recognized the post-Civil War frontier army’s complicity in the near-extermination of the buffalo. Historian Richard White represents the scholarly consensus in stating that ‘various military commanders encouraged the slaughter of bison’ by white hide hunters in order to cut the heart from the Plains Indians’ economy”.

This rise in bison caretaking among Native ranchers can be seen as an attempt to remake history. These data emphasize the importance of the American bison (often referred to as buffalo) for Native communities and highlight the efforts made in Indian Country to actively participate in returning the buffalo to the land.

Many Native nations, especially in the Great Plains, have always had strong relational connections with the buffalo, which were not only hunted for subsistence but were (and are) culturally significant species with which Native peoples maintain kinship ties.

Watch the incredible video below, which features the Quapaw Nation and explains the relationship between bison, culture, and socio-environmental resilience for Native peoples.

In addition to its cultural and subsistence importance in the Great Plains, the American bison is recognized by ecologists as a keystone species, which means that it plays a key role in maintaining the balance of its ecosystem. Indeed, unlike cattle, bison graze the prairie’s delicate soil layers without causing damage, helping plants maintain healthy roots and preventing desertification.

As part of the advancement of the American Dream, bison were slaughtered and replaced with cattle, which became the highest symbol of successful farming and “taming” of the land in the Western mind. Many Native lands were taken out of Native hands for their potential fertility in grazing cattle.

The idea of the American farmer grew around making use of land in ways considered appropriate and useful by the European agricultural model, i.e. to either grow crops or raise cattle. This led to a frenetic race to populate the United States with tamed livestock, leading up to the U.S. producing 52 billion pounds of meat in 2017.

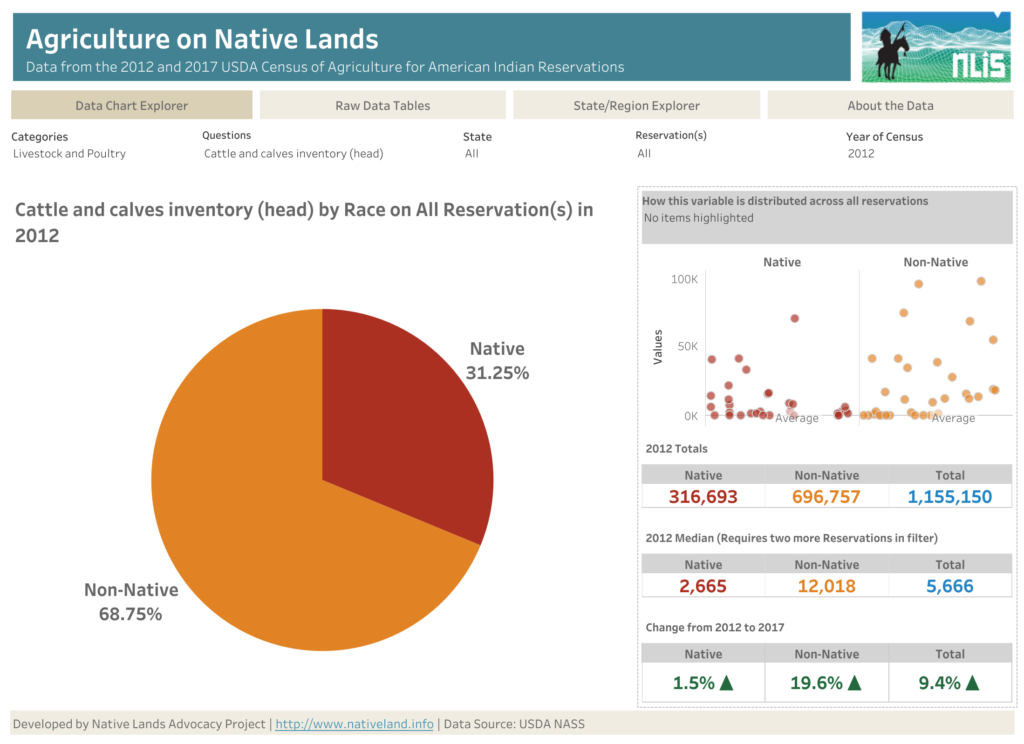

And the beef industry keeps growing. The Census of Agriculture recorded a rise of 7.98% between 2012 and 2017, pushing the number of heads from 38 million to 41 million. This trend is reflected by data on reservations, too. The number of cattle is growing on reservations, but when looking at the racial divide between farm operations, we can see that the number of heads is mostly growing among non-Native farmers and ranchers, with an increase of 19% between 2012 and 2017, compared to only 1.5% among Native farmers and ranchers.

The bison's return supports health and climate mitigation

Far from being random, these numbers reflect cultural differences surrounding agriculture and land use. They also correlate with the dire issues faced by the intensive cattle industry. Beyond its detrimental impact on the land, the cattle industry has contributed to a global increase in cheap meat consumption, whereas most climate scientists agree that livestock is the leading contributing factor to global warming through GHG emissions. Americans are the third leading consumers of meat after Hong Kongers and Australians, with an average of 100kg/year, compared to 43kg worldwide.

Additionally, nutritionists and health specialists are increasingly recognizing how meat-intensive diets contribute to chronic conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. There is also much discussion about the quality of meat ingested, with the proteins’ amino-acid chains being stronger in grass-fed and organic beef than in industrial beef. By contrast, bison meat has lower bad cholesterol and a higher nutritional quality than beef in both grass-fed and industrial ranching.

The significance of this rise of bison ranching in Native Nations cannot be overstated. While non-Native farmers and ranchers seem to be continuing business as usual without seeing the need to reverse the ecological, dietary, and eventual economic catastrophe on the horizon in the cattle industry, Native farmers and ranchers are busy reversing these trends. In regards to the global transformations needed to face climate change and build sustainable food systems, only time will tell which strategy proves most efficient, but the world might learn a thing or two from Native farmers and ranchers.

But even beyond these ecological, dietary, and economic concerns, the return of the American bison to their historical lands signals the cultural and spiritual restoration of Native lifeways.

Written by Dr. Aude Chesnais

Previously titled: Bison numbers increase a whopping 1031% on Native Lands!

Baskin, K. (2020, December 22). The future of meat. MIT Sloan. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/future-meat

Ritchie, H., Rosado, P., & Roser, M. (2017, August). Meat and dairy production. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/meat-production

Smits, D. D. (1994). Frontier Army and the Destruction of the Buffalo: 1865-1883. All About Bison. https://allaboutbison.com/articles-publications/frontier-army-and-the-destruction-of-the-buffalo/

U.S. Department of the Interior. (2022, December 5). Where the Buffalo Roamed. National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/gosp/learn/nature/where-the-buffalo-roamed.htm