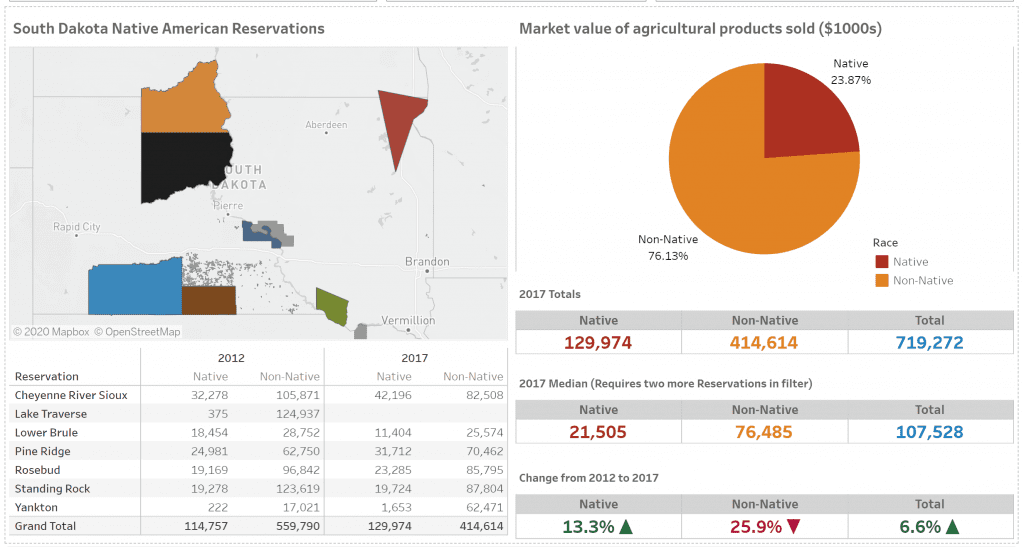

According to the most recent (2017) USDA Census of Agriculture for American Indian reservations, a total of $719 million in agricultural revenue was generated from agricultural production on reservations in South Dakota, yet only 23.87% of that revenue was collected by Native Americans, while non-Native farmers and ranchers collected the rest (76.13%).

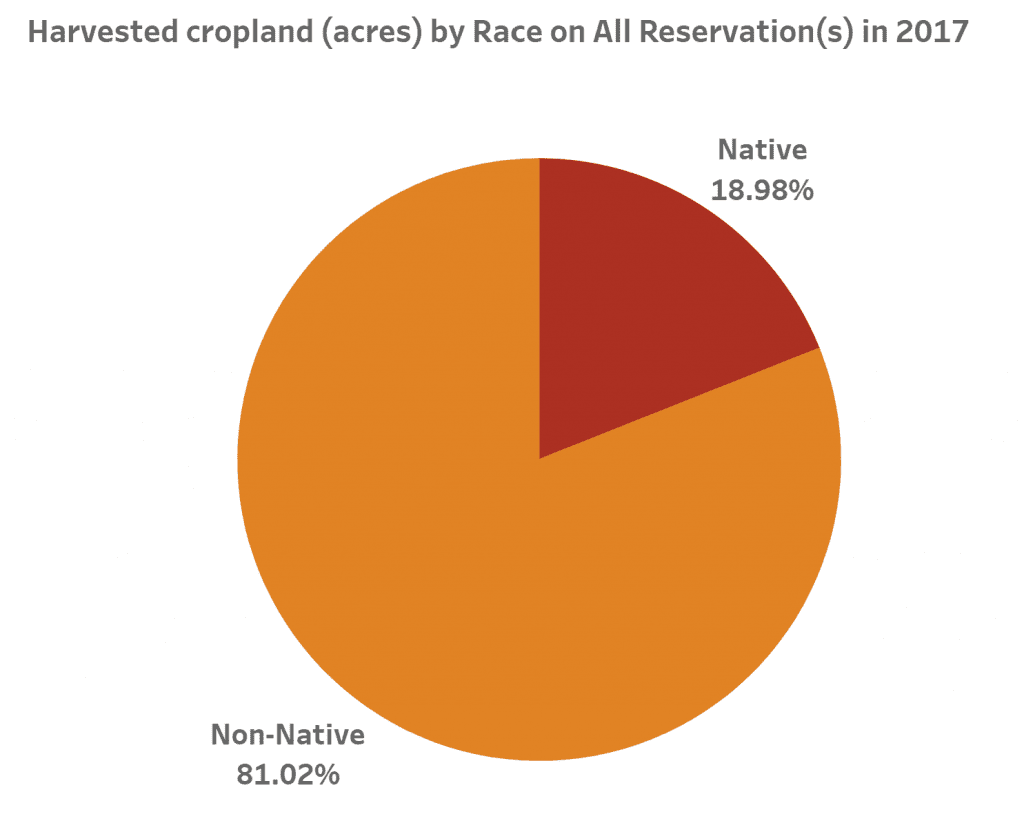

Additionally, 81.02% of the harvested cropland on South Dakota’s reservations is controlled by non-Native producers, compared to only 18.98% controlled by Natives.

However, despite the great disparity between Native and non-Native producers, according to the data, agricultural revenue collected by Native producers on all reservations in the USDA Census has increased by 13.3% since 2012, while revenue collected by non-Native producers has decreased by 25.9%—a sign that the situation may be improving for Native producers.

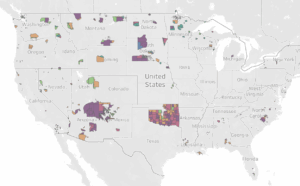

This data is all derived from the USDA Census of Agriculture for American Indian Reservations, for which the Native Lands Advocacy Project has created a helpful interactive dashboard. The dashboard includes data from the Cheyenne River, Lake Traverse, Lower Brule, Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Standing Rock and Yankton reservations and includes a dimension for non-Native producers that is not published in the USDA’s original dataset. This new dimension was created by NLAP by subtracting Native production from the reservation total.

NLAP's Agricultural Census Dashboard

Please note that the image below is from an outdated version of our USDA Census of Agriculture dashboard. The same data for South Dakota’s reservation can be viewed in our updated dashboard here.

This data demonstrates that Native Americans are not the primary beneficiaries of their lands and resources in South Dakota. Unfortunately, the national data identifies an even greater disparity. When you aggregate the data for all 73 reservations that participated in the 2017 Census, Native Americans captured only 12.89% of the agricultural revenue on reservation lands, while non-Native producers on reservation lands captured 87.11% of the agricultural revenue.

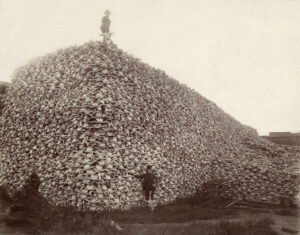

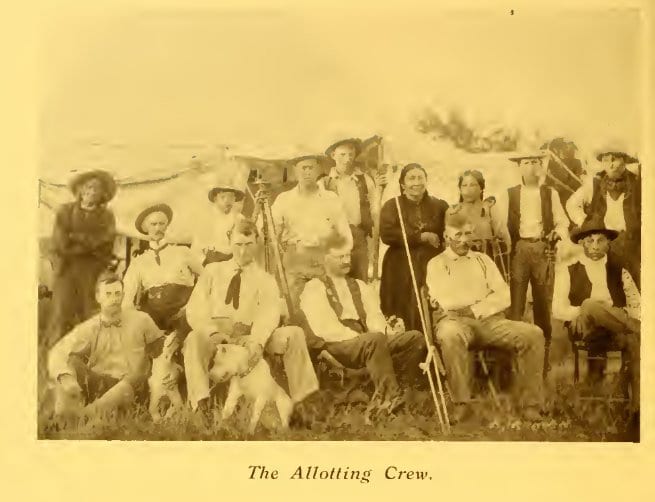

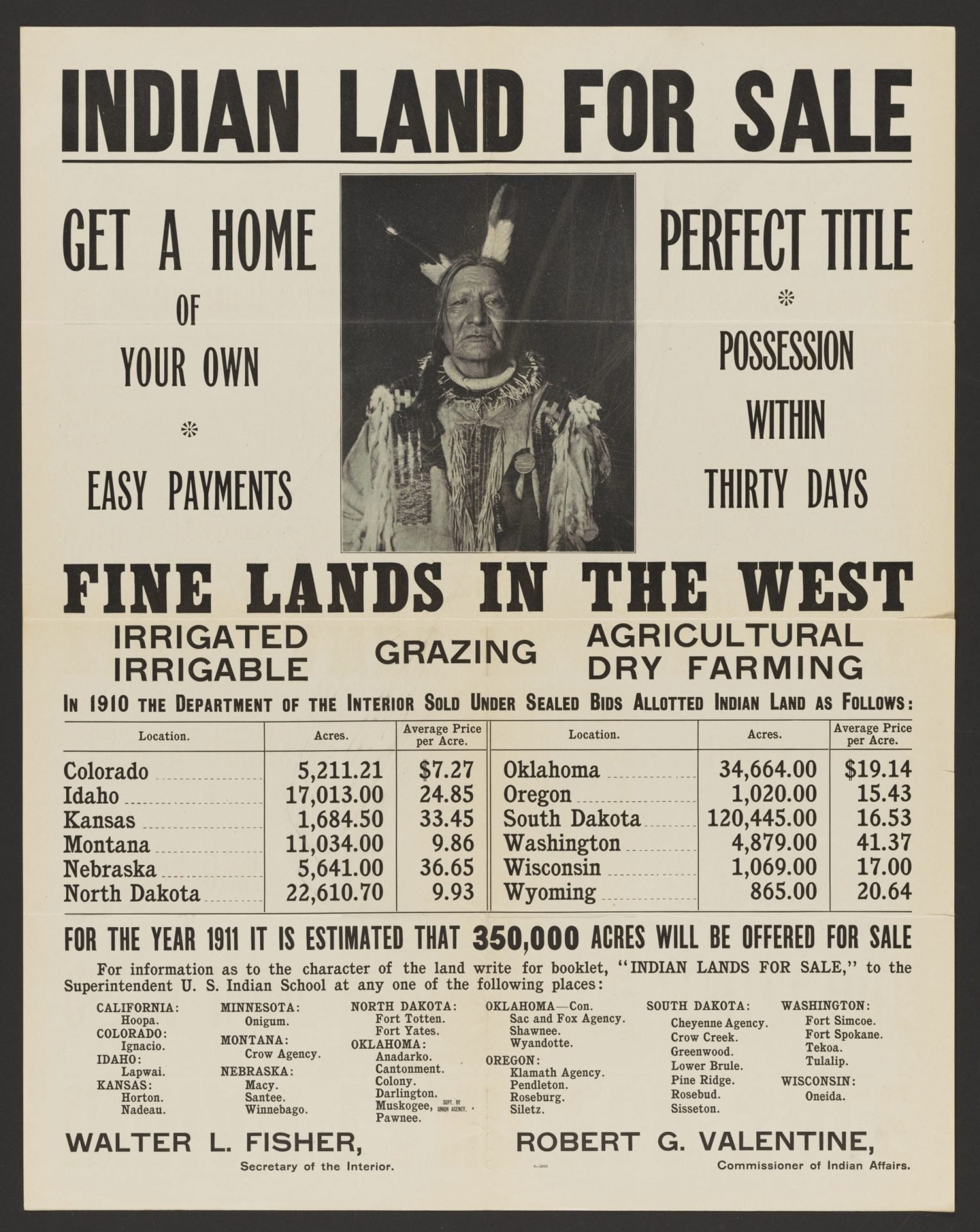

The origin of this disparity on contemporary Native lands can be traced back to the General Allotment Act of 1887 and subsequent acts that broke up Native lands into parcels, and then opened them up to leasing by non-Natives or removed their trust protections, which allowed them to be liquidated to non-Natives. Additionally, evidence suggests that for the past 140 years, the Bureau of Indian Affairs favored leasing and/or liquidating lands to non-Natives over policies and programs that would promote greater Native control over reservation agriculture. See our timeline below of these policies below.

Timeline of Exclusionary Agriculture Policies

The General Allotment Act

Government Opens Native Lands for Leasing

Government Starts Liquidating Reservation Lands

Meriam Report Documents Deprivation Caused by Leasing and Land Sales

Wilson Report Again Criticizes Government Leasing and Calls for Restoration of 25 Million Acres

41 Years After the Wilson Report, Very Little Has Changed

Congress Recognizes Failures of the BIA's Agricultural Support

While tribes enjoy a degree of political sovereignty, it is compromised by the fact that most tribal lands and resources are held in trust by the federal government. Because of this unique relationship, the U.S. Supreme court has repeatedly affirmed and upheld the responsibility that the federal government has to protect tribal lands and assets and ensure they are used for the benefit of Native peoples. This responsibility is known as the Trust Doctrine. In 1977, the Senate report of the American Indian Policy Review Commission described the federal government’s trust obligation as follows:

The purpose behind the trust doctrine is and always has been to ensure the survival and welfare of Indian tribes and people. This includes an obligation to provide those services required to protect and enhance tribal lands, resources, and self-government, and also includes those economic and social programs which are necessary to raise the standard of living and social well-being of the Indian people to a level comparable to the non-Indian society.

Today, many tribes and agriculture support organizations throughout Indian Country are taking proactive steps to reverse the damage caused by 150 years of exclusionary agricultural policies. But the challenge is great and the resources are too few to address numerous interrelated issues, including access to credit, fractionated land ownership, insufficient infrastructure and training, etc. As such, the federal government, as part of its moral and fiduciary responsibility to tribes, must play a large role in reversing the damage caused by 150 years of exclusionary agriculture policies.

Written by David Bartecchi