What climate concerns do tribes across the United States share? How do these climate concerns vary by region? Our Tribal Climate Literature Review identifies preliminary answers to these questions and provides insights to empower tribal climate planning.

Background: Why conduct a Tribal Climate Literature Review?

In the summer of 2023, the Native Lands Advocacy Project (NLAP), a project of Village Earth, conducted a literature review on public tribal climate adaptation plans in an attempt to identify climate trends, projected changes, and conditions on tribal lands to date. In addition, this literature review identifies key areas of concern that Native Nations have for the future of their lands and peoples, as well as identifies data gaps and data needs for effective climate mitigation and adaptation.

This literature review was conducted in the early stage of developing our Climate Data Portal for US Native Lands (with funding from the Native American Agriculture Fund) and the full document can be downloaded here or at the bottom of this blog post. Insights from this literature review were used to inform and guide the development of the Climate Data Portal. This post highlights some of NLAP’s key observations and takeaways from the review.

Data Source & Methods: How was the Tribal Climate Literature Review conducted?

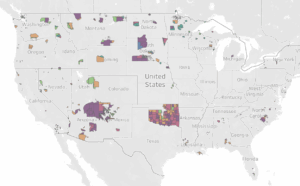

To conduct this literature review, NLAP performed a meta-analysis of 23 public climate change adaptation plans from across the United States of America. These plans represent more than 23 Tribal Nations, as some of them were collaborative efforts. The bulk of these plans come from tribes in the Pacific Northwest, Alaska, and the Great Lakes Regions (see Appendix A at the bottom of this post for the full bibliography of plans). These plans were acquired from the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) database for completed tribal climate change adaptation plans. NCAI’s database is by no means an exhaustive list of tribal climate change adaptation plans, but they are publicly available and provide useful insight into the current status of climate change adaptation planning across Indian Country.

This analysis was conducted using the MaxQDA coding software which allows the user to upload and read documents, and then create and assign classification identifiers to different passages in order to conduct cross-analyses. This enables the user to identify trends and commonalities across multiple documents and identify relationships between identified data topics within and between documents (see Appendix B for a disclaimer about this meta-analysis).

Number of Reviewed Plans by Region

General Findings of the Tribal Climate Literature Review

For this analysis, 125 data topics were identified across the 23 climate change adaptation planning documents. References to these data topics were identified as occurring 2801 times across all plans. It should be noted that these topics are not evenly distributed across the documents as some documents are longer, more detailed, and more holistic while others are more initial planning documents that contain general information on climate change adaptation. Some of the most commonly referenced topics were:

- Traditional/Cultural Resources (272 references),

- Partner Organizations/Agencies (197 references),

- Habitat/Biodiversity (183 references),

- and Indigenous Knowledge (TEK) (137 references).

Apart from “Partner Organizations/Agencies,” these topics highlight the top levels of concern for these Tribal Nations when planning for climate change. Additionally, the identified topics can be used to assess data gaps, as well as areas that will require continued monitoring and updating as climate change impacts unfold. The most commonly cited data topics in these plans were:

- Water (204 references),

- Temperature (167 references)

- Weather (137 references),

- and Migration/Phenology (125 references)

See the chart below for the most frequently referenced data topics across all the plans we reviewed.

Frequency of Data Topic Discussion

Other key commonalities across all regions include:

- Infrastructure: Infrastructure concerns include limited roadways for moving populations (especially in case of emergencies), updating road systems to withstand potential flooding, the need for culvert and sewage reinforcement, updating community buildings to make them more energy efficient and/or to serve as shelters in case of extreme weather conditions.

- Health: Health concerns linked to climate change, primarily stemming from extreme weather, heat, and poor air quality, were discussed in many of these plans. Loss of cultural and traditional resources, foods, and habitats were also discussed as potential causes of decreased health on reservations.

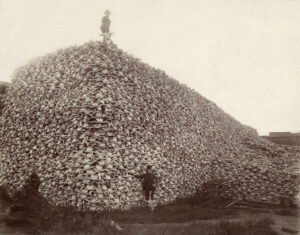

- Invasive Species: These plans focused primarily on invasive vegetation species. These species are typically more readily adaptable to the changing climate and are able to thrive in a wider range of climatic conditions, as well as effective at establishing themselves in degraded soils following ecological disturbances. This poses a threat to many culturally significant species, perpetuating the disconnection between Tribal communities and traditional lifeways.

- Pests: Pests (bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites and the animals that carry them, e.g. ticks, mice, mosquitoes) pose a threat to the health of community members as well as various species (vegetation and wildlife), which further exacerbates the human health implications due to decreases in cultural species and food security.

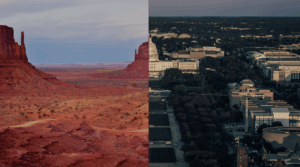

Tribal Nations are not responsible for climate change and are minor contributors, at most, to the environmental destruction of the past 150 years, and yet they are some of the most directly impacted by the changing climate. Therefore, the plans these communities produced were focused on identifying current and predicted issues in order to prepare for them, and on increasing the resiliency of the people, the culture, and the lands.

Regional Profiles: How do Tribal climate concerns vary by region?

As discussed above, tribal nations across the U.S. share many climate concerns and are attentive to many of the same key climate indicators on their lands. However, NLAP identified specific regional trends regarding how these broad concerns applied to tribal lands and bioregions. See an overview of these regional differences below.

Pacific Northwest

The most commonly referenced topics in public climate adaptation plans from the Pacific Northwest included: Traditional/Cultural Resources, Food Security, Water, and Health.

Alaska

The most commonly referenced topics in public climate adaptation plans from Alaska included: Traditional/Cultural Resources, Food Security, Water, and Health.

Great Lakes

The most commonly referenced topics in public climate adaptation plans from the Great Lakes included: Vegetation, Traditional/Cultural Resources, Invasive Species, and Habitat/Biodiversity.

Southwest

The most commonly referenced topics in public climate adaptation plans from the Southwest included: Water, Partner Organizations/Agencies, and Infrastructure.

Northeast

The most commonly referenced topics in public climate adaptation plans from the Northeast included: Water, Traditional/Cultural Resources, Habitat/Biodiversity, and Infrastructure.

Recommendations

While this review is a good starting point, the use of published planning documents poses an issue in terms of planning biases. There are far more Tribal Nations and communities than there are completed plans. This means that the needs and trends found across these plans may not be wholly representative of the needs and trends across all of Indian Country, but more tailored to the tribes that have the capacity to create climate change adaptation plans.

There are many possible reasons for tribes not completing a climate change adaptation plan. Not knowing where to begin or what processes to follow, not having access to relevant data, lack of funding, lack of capacity, lack of support from the community or tribal government as well as a host of other reasons could be responsible for incomplete or nonexistent planning documents. One way that external organizations can help is by making relevant data and technical support freely available to tribes. This is where resources like this review become relevant.

By identifying needs and trends across a select number of plans, we are able to better understand the status of climate change adaptation planning in Indian Country. This understanding then directs our research, data acquisition, and resource production to fill those identified needs. From there, more literature reviews can be completed as a greater number of plans are developed, enabling the fine tuning and progression of data development and production.

Tribal Nations are already experiencing climate change in their communities, regardless of where they are in their climate change planning process. By using regional data and projections in addition to traditional ecological knowledge for monitoring their local environments, they are adapting to their changing environment as they have done for generations and will continue to do for generations more.

NLAP's Commitment

The Native Lands Advocacy Project remains committed to providing free, public data tools that empower sovereign tribal decision-making. In the fall of 2024, we launched the Climate Data Portal for US Native Lands, which compiles key data tools for tribal climate planning. Learn more about this portal and access the full tribal climate literature review below.

Author

Blog post written by Emma Scheerer

Full literature review (available here for download) written by Chase Christopherson and edited by Emma Scheerer

Appendix A: Bibliography

Alaska Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development, Division of Community and Regional Affairs (2011). Relocation Report: Newtok to Mertarvik. State of Alaska. Anchorage: Prepared by Agnew: Beck Consulting with PDC Engineers and USKH Inc. for the Alaska Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development, Division of Community and Regional Affairs.

Central Council of the Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska (2019). Climate Change Adaptation Plan.

Clark, K., Harris, J. (2011). Clearwater River Subbasin (ID) Climate Change Adaptation Plan. A collaboration between the Nez Perce Tribe Water Resources Division, University of Idaho, Nick and Marci Gerhardt, Columbia River Intertribal Fish Commision, USDA Forest Service-Nez Perce and Clearwater National Forests, Senator Risch’s Office, and Senator Crapo’s Office.

Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (2015). Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. Nasser, E., Petersen, S., Mills, P. (eds). Available online: www.ctuir.org.

Durglo Jr., M., Durglo, J., Janssen, R., Matt, R., Matt, C., Incashola, T. (2016). Climate Change Strategic Plan, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation.

Jasperse, L., & Pairis, A. D. (2019). La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians Adaptation Plan: 2019 Living Document. In collaboration with the La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians Environmental Protection Office. Climate Science Alliance.

Karuk Tribe (2019). Karuk Climate Adaptation Plan. Karuk Tribe.

Krosby, M., Morgan, H., Case, M., Whitely Binder, L. (2016). Stillaguamish Tribe Natural Resources Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. Climate Impacts Group, University of Washington.

Jourdain, J. & Thaler, T., Griffith, G., Crossett, T., Perry, J.A.; (Eds). (2014). Mitigwaki idash Nibi: A Climate Adaptation Plan for the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians. Model Forest Policy Program in association with Red Lake Department of Natural Resources and the Cumberland River Compact; Sagle, ID.

Natural Systems Design (2014). Flood and Erosion Hazard Assessment for the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe Phase 1 Report for the Sauk River Climate Impacts Study. In collaboration with Scott Morris, Watershed Director of Sauk Suiattle Indian Tribe.

Navajo Nation Department of Fish and Wildlife, Tam, G., Begay, C., Yazzie, R. (2018). Climate Adaptation Plan for the Navajo Nation. A collaboration between the Navajo Nation Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals, and Northern Arizona University Division of Natural Resources.

Norgaard, K. M. (2014). Karuk Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the Need for Knowledge Sovereignty: Social, Cultural and Economic Impacts of Denied Access to Traditional Management. Karuk Tribe.

Pala Band of Mission Indians (2019). Pala Band of Mission Indians: Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. Prepared by Pala Environmental Department and Prosper Sustainability.

Panci, H., Montano, M., Shultz, A., Bartnick, T., Stone, K. (2018). Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment: Integrating Scientific and Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commision.

Petersen, S., Bell, J., Miller, I., Jayne, C., Dean, K., Fougerat, M. (2015). Climate Change Preparedness Plan for the North Olympic Peninsula. A Project of the North Olympic Peninsula Resource Conservation & Development Council and the Washington Department of Commerce, funded by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Puyallup Tribe of Indians (2016). Climate Change Impact Assessment and Adaptation Options. A collaboration of the Puyallup Tribe of Indians and Cascadia Consulting Group.

Qatalina Schaeffer Sr., J., Rittgers, A., Johnson, P., Davis, A., Grunau, B., Hebert, J., Doyle, M. (2019). Oscarville Tribal Climate Adaptation Plan. In collaboration with the Oscarville Traditional Village Council, Oscarville Native Corporation, and the Association of Village Council Presidents. Cold Climate Housing Research Center.

Scott, J., Wagner, A., and Winter, G. (2017). Metlakatla Indian Community Climate Change Adaptation Plan. A collaboration between the Metlakatla Tribal Council, Climate and Energy Department, Fish and Wildlife Department, Tamgas Creek Fish Hatchery, Forestry and Natural Resources, Duncan Cottage Museum, Annette Islands School District, Metlakatla Community Members, and Sealaska Corporation.

Shinnecock Indian Nation (2013). Shinnecock Indian Nation Climate Change Adaptation Plan. In collaboration with Shinnecock Indian Nation Council of Trustees.

Stults, M., Petersen, S., Bell, J., Baule, W., Nasser, E., Gibbons, E., Fougerat., M. (2016). Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Plan: 1854 Ceded Territory Including the Bois Forte, Fond du Lac, and Grand Portage Reservations. Duluth, MN: 1854 Ceded Territory.

VERBI Software. (2021). MAXQDA 2022 [computer software]. Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software. Available from maxqda.com.

Wagner, G., Reuling, M., Khumalo, L., Paul, K., Cross, M. (2018). Blackfeet Climate Change Adaptation Plan, Blackfeet Nation. A collaboration between the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Tribal Resilience Program, the Great Northern Landscape Conservation Cooperative, and the National Indian Health Board.

Water Resources Division, Lummi Natural Resources Department (2016). Lummi Nation Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Plan: 2016-2026. Project funded by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (Assistance Agreement No. BG-97042602-4).

Yakama Nation (2016). Climate Adaptation Plan for the Territories of the Yakama Nation. In collaboration with Cascadia Consulting Group, SAH Ecologia LLC, and the University of Washington Climate Impacts Group.

Appendix B: Disclaimer

This meta-analysis is not intended to be representative of all Tribal Nations and their planning processes, nor do these findings represent data needs and concerns for all Tribal Nations. This is an ongoing process as the impacts of climate change evolve, as new data and technologies are created, and as more Tribal Nations prepare for and respond to climate change. NLAP’s literature review is an initial analysis of trends in climate change adaptation planning across Tribal Nations; it serves as a preliminary guide for initiating discussions. The report is not intended to be an exhaustive analysis, nor does it provide in-depth analyses on the specifics contained within individual planning documents.