In the summer of 2023, the Native Lands Advocacy Project developed a Historic Loss Assessment—articulating lost lives, lands, and resources for the Native Nations of Colorado—for the Truth, Restoration, and Education Commission (TREC) of the People of the Sacred Land. The findings of the TREC can be viewed here in three comprehensive reports.

NLAP was honored to be included in this work, and in the process of developing the Historic Loss Assessment, our team came to realize the power these tools have for correcting historically harmful narratives and advocating for true and equitable pathways forward. This series of blog posts (start here) outlines some of the processes and data tools NLAP developed to complete this assessment. This series is not a comprehensive review of the final TREC assessment; rather, through these posts, we aim to promote the usefulness of such a tool so that these assessments may be completed in more states.

This blog post covers two sections of a Historic Loss Assessment:

The previous post in this series outlines the various ways the final Historic Loss Assessment mapped and quantified land loss for the Native Nations of Colorado. In this post, we walk through the next two sections of the assessment: Illegal Settlements and Loss of Agricultural Revenue.

Illegal Settlements

Section 11 of the 1834 U.S. Non-Intercourse Act states “that if any person shall make a settlement on any lands belonging, secured, or granted by treaty with the United States to any Indian tribe, or shall survey or shall attempt to survey such lands, or designate any of the boundaries by marking trees, or otherwise, such offender shall forfeit and pay the sum of one thousand dollars. And it shall, moreover, be lawful for the President of the United States to take such measures, and to employ such military force, as he may judge necessary to remove from the lands as aforesaid any such person as aforesaid.”

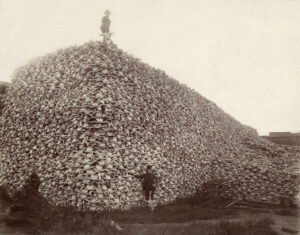

When U.S. citizens settled in unceded lands, these impositions were not only morally and practically objectionable (in violating those Native Nations’ ancient relationships with their lands), but clearly illegal according to existing laws—irrespective of the U.S. government’s repeated failures to penalize its own citizens.

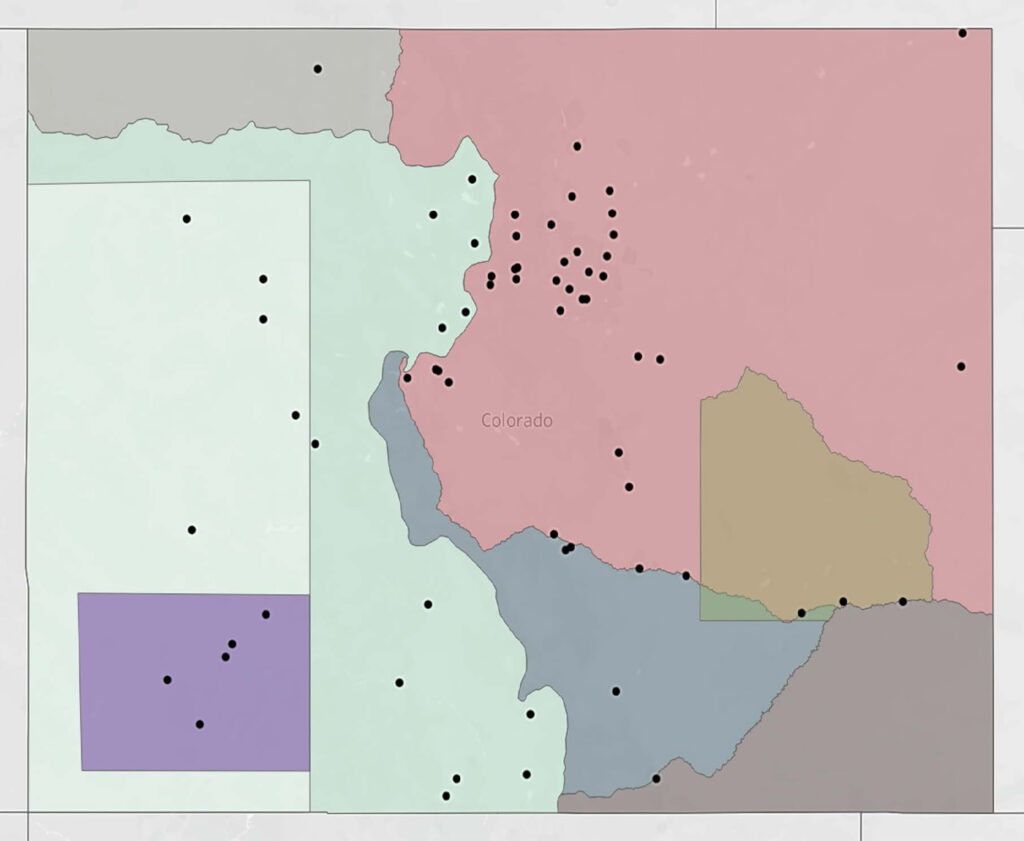

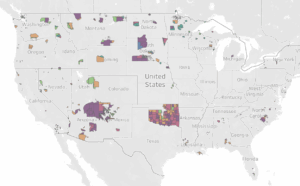

For this section of the Historic Loss Assessment, NLAP developed a non-comprehensive database of illegal settlements in Colorado. Towns and cities that remain occupied into the present day were prioritized; however, because of Colorado’s mining history, ghost towns and abandoned settlements were also added in order to help round out the data. A more comprehensive study of illegal settlements could be useful for advocacy and educational purposes, and the Historic Loss Assessment makes recommendations for such further research (see p. 98).

The Historic Loss Assessment reports 66 illegal settlements in Colorado, shown in the map above and grouped by cession in the table. The earliest illegal settlements mapped by NLAP include:

- Pueblo: settled when “Jacob Fowler and his men [built] a three-room house on the site of present-day Pueblo, Colorado,” on January 3, 1822 (Hafen, p. 70). Pueblo was illegally settled 39 years before Cession 426 was ceded in 1861.

- Florence (originally Hardscrabble Creek): settled in 1840 “by Bent, St. Vrain, Beaubien, Maxwell and others just east of present-day Florence, Colorado” (Hafen, p. 104). Hardscrabble Creek was illegally settled 21 years before Cession 426 was ceded in 1861.

- Rico: “Prospectors first staked land along the Dolores River in the 1860s, marking the area that would later become known as Rico” (Uncover Colorado). NLAP designated the year 1860 as Rico’s settlement date because sources indicate it was settled during the gold rush, but the exact year may have differed. Cession 566 wasn’t ceded until 1874, meaning Rico was illegally settled about 14 years before cession.

This section of the Historical Loss Assessment also found that ten of Colorado’s fifteen most-populated cities were settled in unceded Native lands (Denver, Colorado Springs, Lakewood, Arvada, Pueblo, Westminster, Centennial, Boulder, Longmont, and Loveland). To explore the data & the primary sources, view the full Historic Loss Assessment.

While land history varies by state and regional particularities must be kept in mind, mapping illegal settlements is helpful for documenting and visualizing the breadth of settler imposition on Native communities. Notably, in the Historic Loss Assessment for Colorado, a broader picture emerges in which coercive treaty agreements, mineral extraction, and violent incidents were consistently preceded by illegal settler incursions onto unceded Native lands.

Loss of Agricultural Revenue

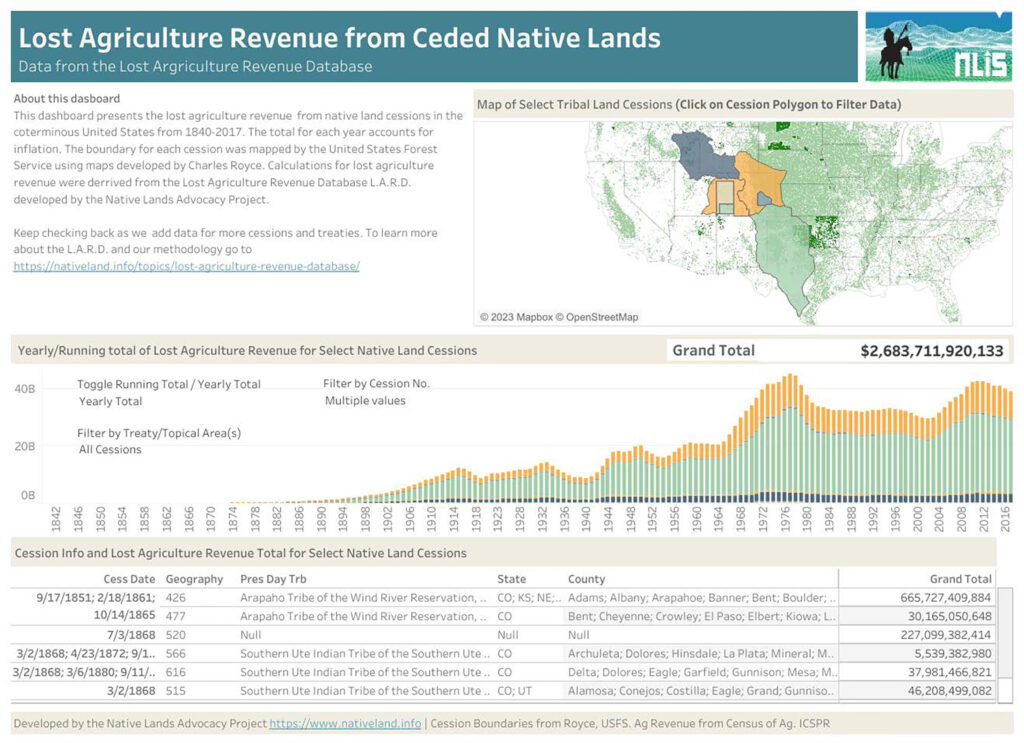

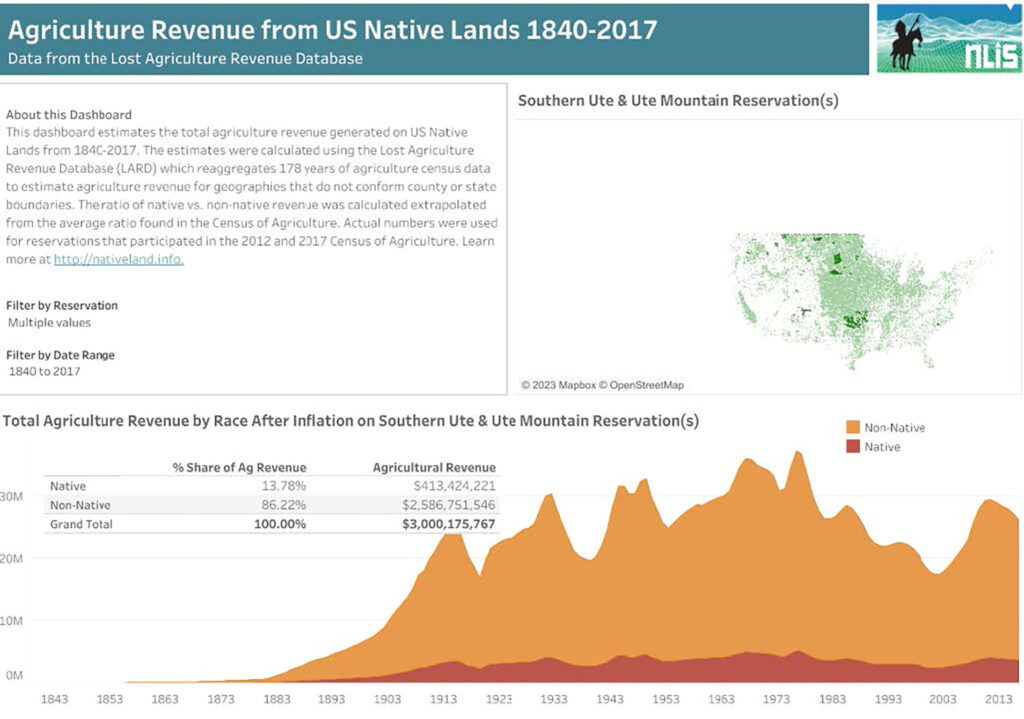

The Lost Agriculture Revenue Database (L.A.R.D.) was developed in 2020 by the Native Lands Advocacy Project to help quantify the impacts of land cessions and discriminatory agriculture policies of the United States government. The L.A.R.D. contains two tools:

- Lost Agricultural Revenue from Ceded Native Lands: This dashboard makes it possible to view the total lost agriculture revenue from one or more cessions. While the calculations are approximate, this dashboard nonetheless posits a concrete value for the financial gains settlers have enjoyed as a result of removing Native Nations from their lands. In many cases, the capital accumulated through these land cessions contributed directly to further settler expansion and development. Inversely, this database calculates the loss of economic potential for all Native Nations within their ceded lands.

- Agriculture Revenue from U.S. Native Lands 1840-2017: This dashboard calculates the differences in agricultural revenue made by Native and non-Native producers on contemporary reservations. Often, these disparities in revenue are due to discriminatory agriculture and land policies imposed by the U.S. government onto Native Nations.

To read about how the L.A.R.D. was developed, see this page, and to read some brief, nationwide data observations from the L.A.R.D., see this blog post.

The Historic Loss Assessment reports $2,683,711,920,133 in lost agricultural revenue for the seven ceded lands of Colorado (image below). Note that this dashboard can be filtered for other cessions, but for the purposes of this report selected only those cessions relevant to Colorado.

Furthermore, the L.A.R.D. estimates major disparities in agricultural revenue between Native and non-Native producers on the two federally recognized reservations in Colorado (see image below). As with the dashboard for ceded lands, this L.A.R.D. dashboard can be filtered for any reservation in the U.S.

These disparities should not be viewed just as dollar amounts. For Native communities, land has always represented much more than potential profit, and communal wellbeing is not solely measured by economic success. However, this database adds an important piece to the overall picture, representing how settlers have profited and continue to profit from disconnecting Native Nations from their homes and livelihoods.

This blog post is part of a series that documents our processes in creating a Historic Loss Assessment for the Truth, Restoration, and Education Commission (TREC) of the People of the Sacred Land. To view the landing page for the rest of the series, click here.

Written by Emma Scheerer

Act of June 30, 1834, Pub. L. No. 23-161, § 12, 4 Stat. 729, 730 (codified as amended at 25 U.S.C. § 177 (2006)).

Colorado and Its People, ed. LeRoy R. Hafen, vol. 1, retrieved from Denver Library’s Colorado Chronology, https://history.denverlibrary.org/sites/ history/ files/Colorado%20Chronology%202020.pdf.

“Rico, Colorado,” Uncover Colorado, https://www.uncovercolorado.com/ towns/rico/.