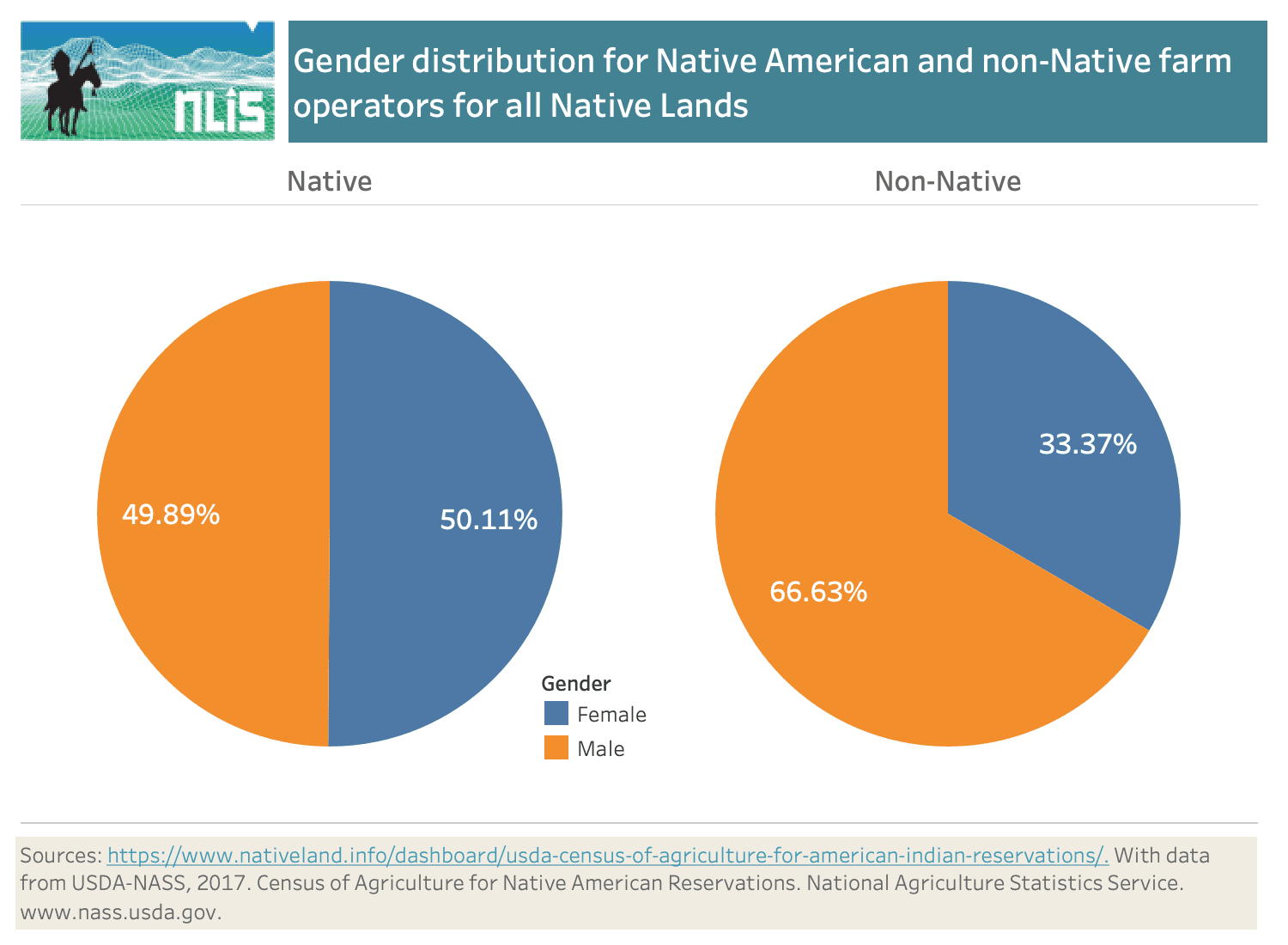

Increasing the proportion of women in agriculture has been a longstanding goal of agencies like USDA, FSA and programs like 4H but these programs may be able to learn a thing or two from Indian Country which has nearly equal participation among men and women. This is according to data collected in the 2017 USDA Census of Agriculture for American Indian Reservations and analyzed by the Native Lands Advocacy Project. The data shows that women comprise over 50% of the Native American Farmers and Ranchers operating on Native American Reservations and nearly 46% of the Native American operators nationwide. This is compared to only 33.37% women participation for non-native farm operators.

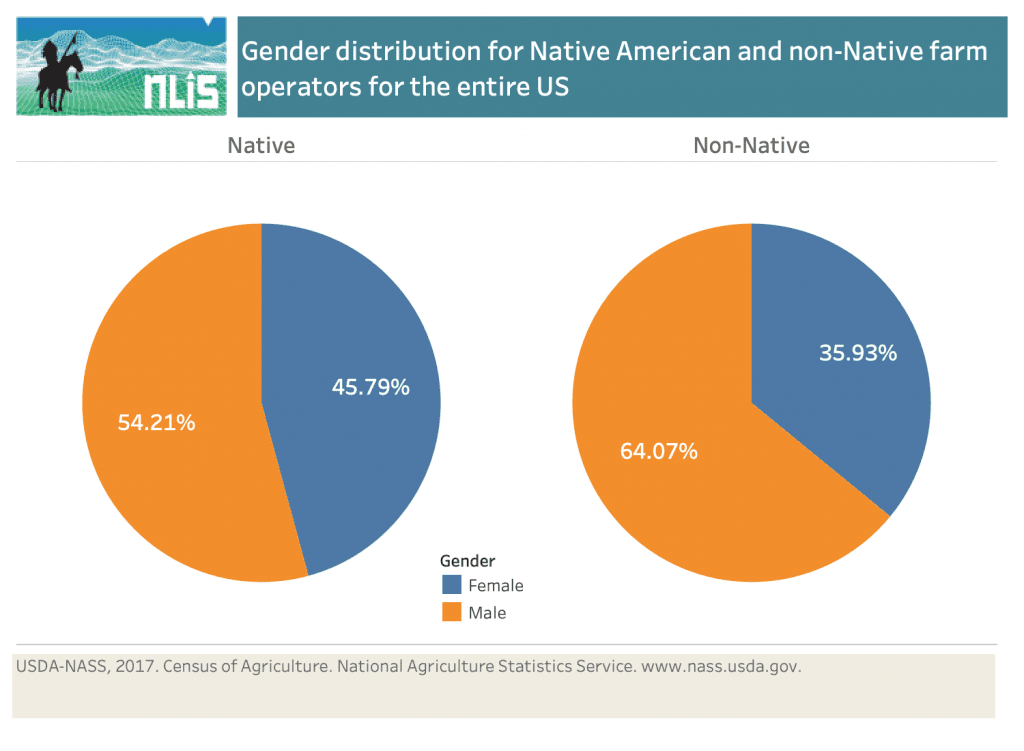

And this is not a phenomenon restricted to American Indian/Alaskan territories. The same equality pattern is found when comparing agriculture data from reservation lands only with the rest of the US (see Figure 2). Although native women’s representation decreases compared to native land data, they still make up 45.79% of operators compared to 35.93% for non-native women operators. Therefore across two datasets, Native American farmers and ranchers still have greater equal gender representation than non-Natives.

Women and Agriculture

Women have always played a key role in farming, but too often has that role been undermined or remained unseen. To understand the relationship between women and agricultural issues in the global economy, we need to look at the way that gendered economic activities maintain and reproduce a mode of production based on capital extraction. The influence that women have played and keep playing on working land and ensuring agricultural production worldwide is tremendous, yet has often been kept invisible by patriarchal institutions that have relegated women to domestic activities.

From the European feudal agricultural systems to modern western capitalism, women have been historically kept from owning and managing farmland outside the bounds of marriage. Women have been “permitted” in the farm space as farmers’ or landlords’ wives and as such traded just like any other capital within the economic system. Brides often used to be traded for land ownership or access to land, or for the economic capital they would bring to an exploitation from their family’s heirship, but had little control or management of land assets outside these terms. Occasionally, widows would be allowed to manage land, usually for the benefits of lawful children’ interests.

These patterns have continued on in the formation of America’s farmland. Although history school books are quick to suggest that the American dream was promoting access to land often refused to settlers on the old continent, they forget to tell how that land was “given” to some people to the complete exclusion of others. “Settlers” when it comes to property ownership almost exclusively refers to male settlers, whereas women are mentioned in official documents alongside children in terms of their mental capacity to manage assets. Women farmers are therefore usually absent from the narrative outside of their marital and domestic participation.

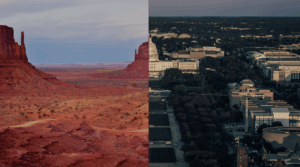

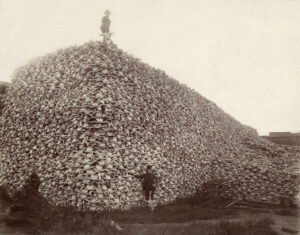

Additionally, Native people altogether are absent and/or misrepresented in the narrative. First and foremost, all of US land was extracted by conquest from Native People (see details on our Stolen Futures Storymap). But additionally, and in total contrast with the myth of manifest destiny, where settlers supposedly settled on idle or wild land, these White men were given lands that were managed and even often cultivated by Native nations. Some nations were mostly agriculturalists, while others still practiced sustainable and rotational land stewardship over the resources that they relied upon. In that context, women’ roles greatly differ from nations to nations, but it is widely documented that their place in the food-system was usually more egalitarian.

In some nations, women would head societies that would be responsible for making decision over land use, and would be tasked to decide when to harvest and migrate accordingly. Women were also often found to be the head or even owner of the family’s house, even in nations organized around land stewardship instead of land property. Despite great inter-tribal differences, it is clear that women’ roles in agriculture was much differently lived in pre-contact North America than in Europe and early US settlements. It is important to realize women’ relationships with their environment and to land use and agriculture is affected by the mode of production and has been historically defined by the western understanding of land as commodified and owned capital.

Final Thoughts

This analysis reveals that women are better represented in native agriculture than non-native agriculture. Although it does not tell us about the reason why, it does raise important questions. The issue of women in farming goes much further than gender representation. According to recent studies, when women manage and farm land, they are more likely to engage in conservation practices and make decision that take the long-term effects of farming practices into consideration such as their impact on people and soil’s health. A similar claim can be made of indigenous peoples, who live on 24% of the world’s land, which also contains more than 80% of the world’s biodiversity. In the face of climate threats, global institutions are starting to realize the potential of traditional ecological knowledge, for instance in recent events the need to incorporate landscape slow burning in order to mitigate fire hazards. This really emphasizes the positive impact of indigenous women in agricultural production.

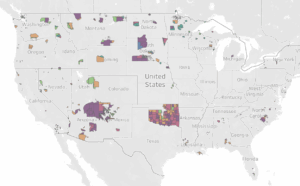

Looking at the intersection of social categories such as race and gender (otherwise called intersectional studies) can really shed light on social problems as opposed to simply looking at aggregated numbers. Here, being Native seems to have a positive effect on gender representation in farming. However, it does not mean that native farmers are better off altogether. In the contrary, hundreds of years of discriminatory agricultural policies continue to disrupt native farmers’ access and control of their own lands for farming. As exemplified by this recent dashboard, of all agricultural revenue produced on native land, an average of 87.11% goes to non-native farmers and ranchers. This inequality can be traced back to the history and organization of native land tenure in the US.

Much work is still needed to reach the gender and racial equality in farming required to create a sustainable food-system for all. But this data suggests that Native farmers and ranchers are better at including women in the process and that non-Native farmers and ranchers have a longer way to go.

Some references

Header Image by Felix Earle, used with permission

Banu, Z., & Thamizoli, P. (1998). Indigenous women, seed preservation and sustainable farming. Journal of Human Ecology, 9(2), 181-185

Shortall, S. (1999). Women and farming: Property and power. Springer.

Sachs, C. E. (2018). Gendered fields: Rural women, agriculture, and environment. Routledge.