Previously, in one of our most popular blog posts, NLAP highlighted the prominence of female-led agricultural operations on Native reservations:

The data [from our Agriculture on Native Lands Dashboard] shows that women comprise over 50% of the Native American Farmers and Ranchers operating on Native American Reservations and nearly 46% of the Native American operators nationwide. This is compared to only 33.37% of women participation for non-Native farm operators.

- Quote from the blog post “Women’s Representation in Agriculture Greater Among Native Americans."

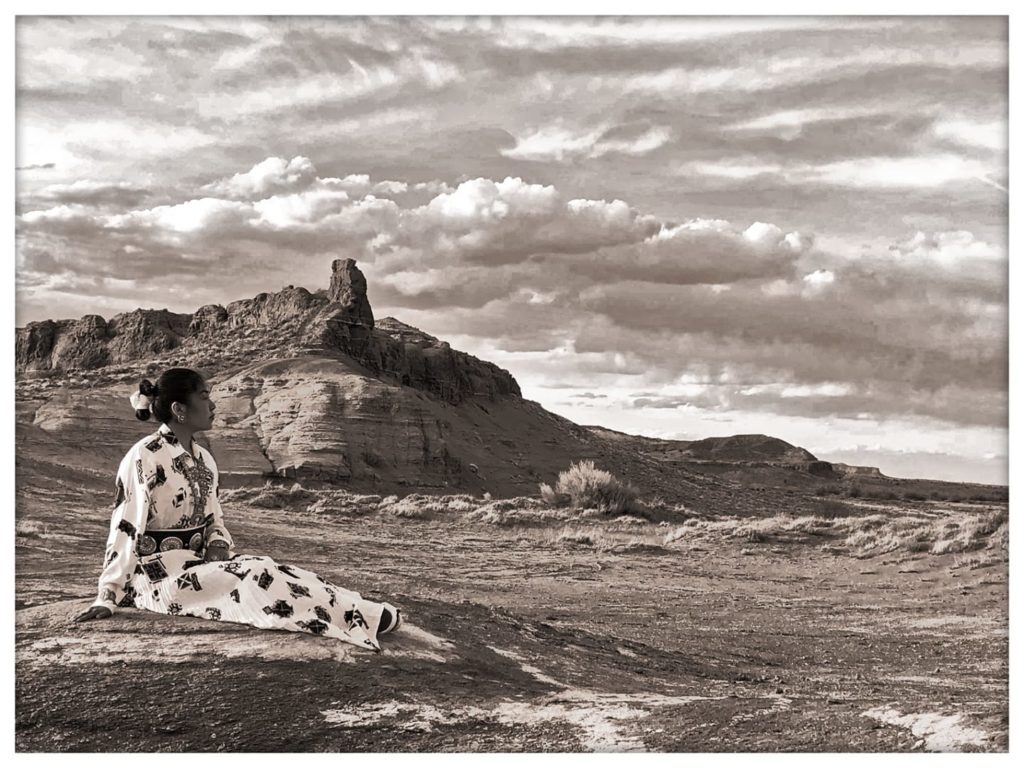

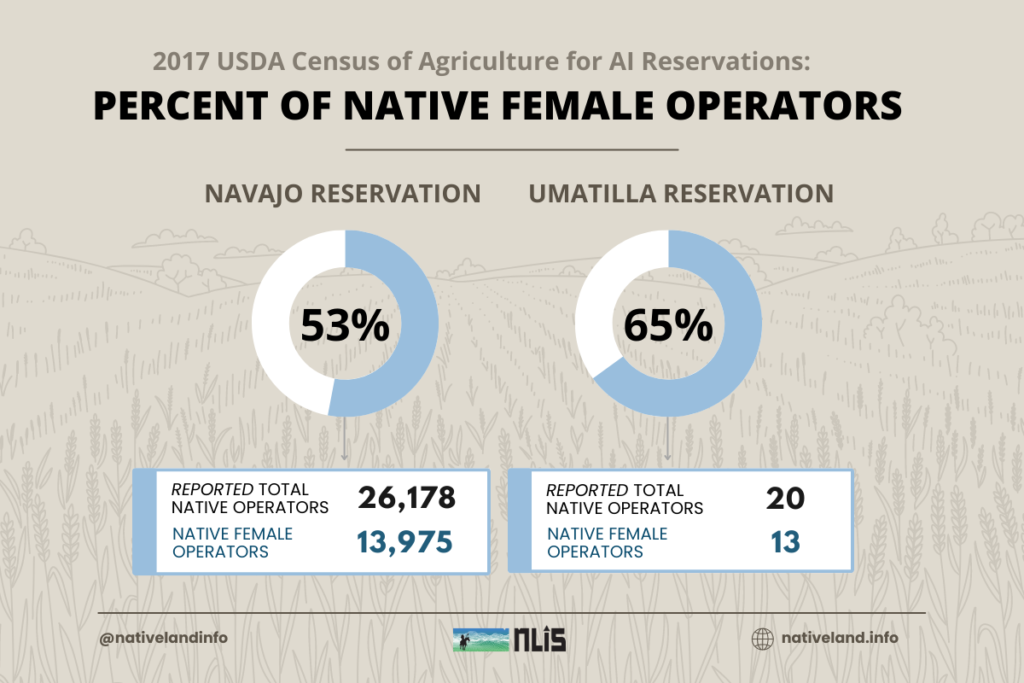

To further this initial observation, we spotlight the Census of Agriculture data for the Navajo Nation and how Diné Asdzáán (Navajo women) make up over half (53%) of Navajo’s agricultural producers.

In this blog post, we present this data finding as a manifestation of the historically powerful and influential role of women in Navajo communities. Even in the case of the land’s non-Navajo, Native female operators, the matrilineal culture of the Navajo Nation, and many other Native Nations, provide the necessary foundation for such exceptional trends in agricultural leadership.

What Does the Data Say?

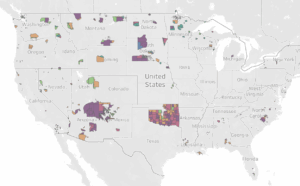

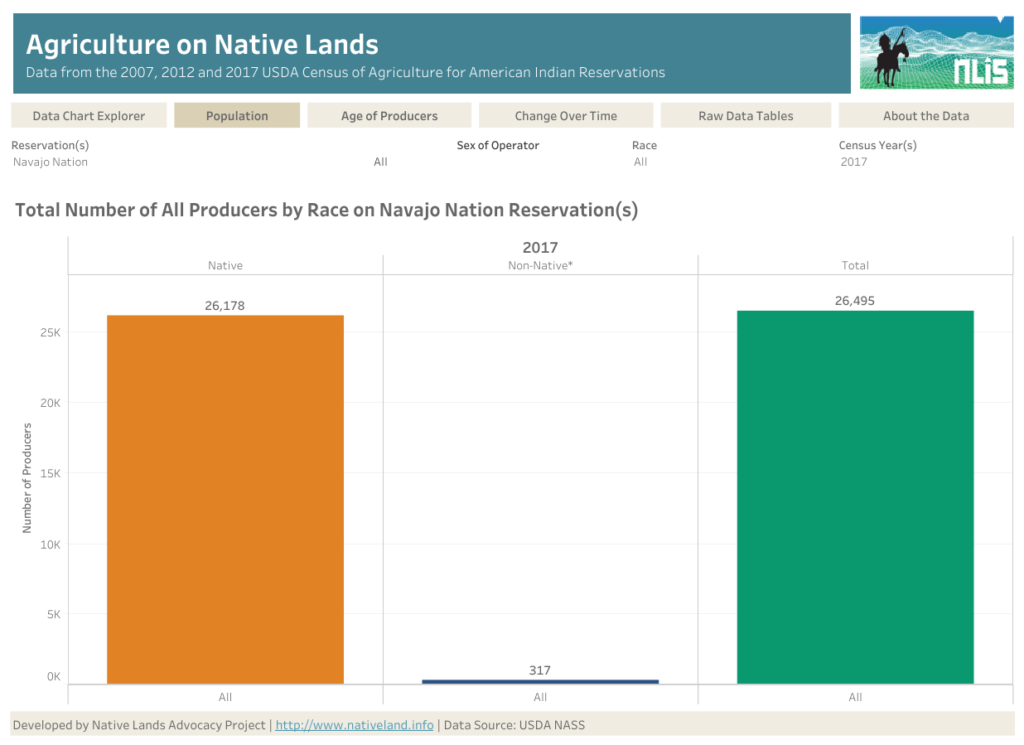

According to the most recent Census of Agriculture data for American Indian Reservations, 26,495 producers were operating on the Navajo reservation in 2017. Of this total, 26,178 (98%) producers were Native.

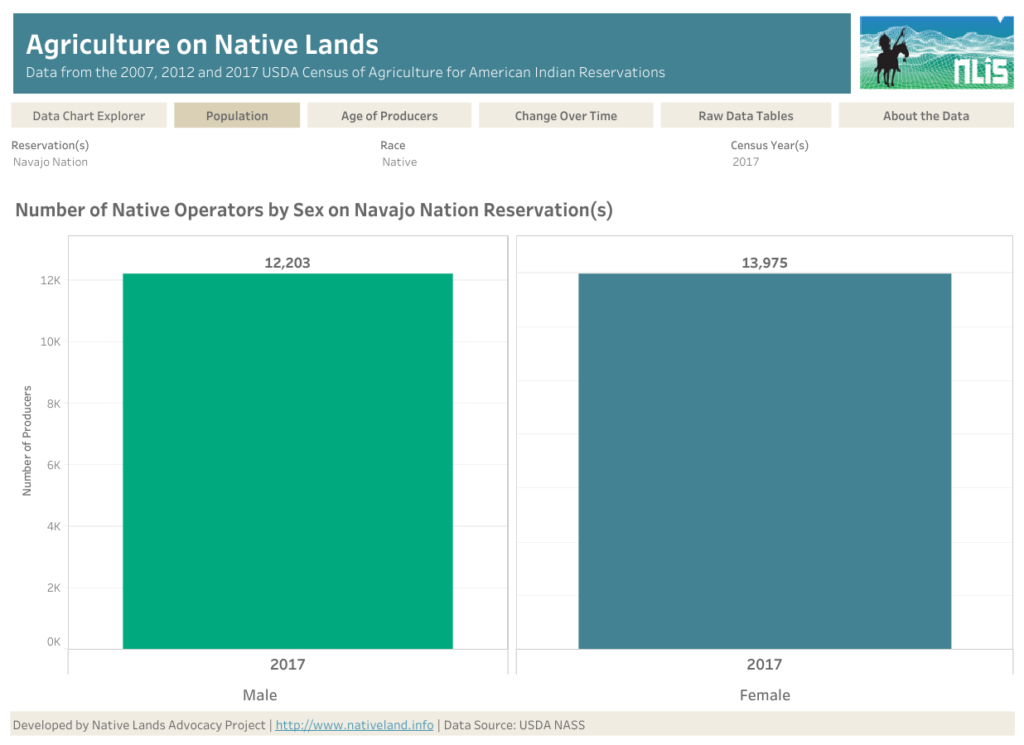

Examining these numbers even further, we utilize the new features added to this data dashboard to view the gender breakdown of these operators. As observed in the dashboard screenshot below, over half (53% or 13,975) of the Native operators on the Navajo reservation are women.

When we look at all 73 reservations that participated in the most recent Census of Agriculture, only* the Navajo Nation and the Umatilla Confederated Tribes reported a Native female majority among their agricultural operators.

*More accurate and comprehensive data on Native agriculture would tell us more about operator trends for the many other Native communities not included in the Census of Agriculture.

However, the data we do have can still provide us with a glimpse into the change-making happening in Native agriculture.

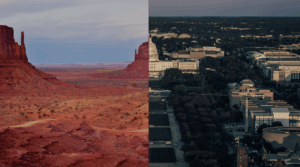

A Foundation for Navajo Agricultural Leadership

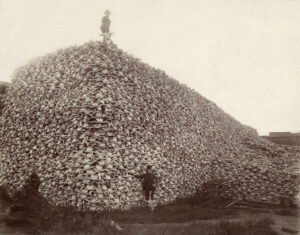

The modern agricultural system was initially created to destroy the collective care of the land by furthering an individualized and commodified agriculture system. However, despite this exclusionary history, Native Nations have recovered a vision for their agricultural systems that better represents their values. For tribes, present-day farming and ranching represent a prosperity that is more than just numbers–they represent the strategic outpourings of love for community and land, in which the enduring goal is relational and ecological balance. As far as Census observations go, what is happening in Navajo agriculture affirms that Diné Asdzáán are leading the way in achieving this balance. This should come as no surprise, considering the traditional high station that Navajo women maintain in their communities.

To better grasp the data for the Navajo Nation, we should understand that the Navajo Nation is inherently matriarchal. Like many other Native Nations, the women in Navajo communities carry and craft most of the traditions, language efforts, story-making and telling, and character-shaping. Writing as one who grew up on the Navajo reservation, I thrived under the nourishing light of my mother, grandmothers, aunties, and other asdzáán leaders who managed our community and homelands well.

Matriarchy, from Diné perspective, is a woman who leads and makes hard decisions for her family, not only determining their diets but also through challenges beyond her control, such as severe droughts and unexpected weather changes impacting the environment and ecosystems around the communities.

Leiloni Begaye, “Diné Women in Agriculture and the Importance of Our Water,” USDA Climate Hubs.

Historically and still today, Navajo women ensured the health of their communities by tending to the land, employing and protecting water, caring for livestock, and securing good trade.

For example, Navajo women often owned the majority of resources and property due to Navajo matrilineal tradition. Therefore, even as Navajo people adapted to new agricultural systems (while simultaneously rebuilding their ancestral land caretaking), Navajo women naturally assumed a managerial role over any new livestock, crops, and agricultural trade. Additionally, as home leaders, Navajo women primarily stewarded their families’ diets. The responsibility of ensuring the family’s health meant that Navajo women (who managed an agricultural operation) took special notice and care for cultivating nutritious, traditional crops. Although many more examples and stories could be told of Navajo women leading the way in agriculture, one of the most powerful aspects of traditional Navajo female leadership is their role as wisdom keepers and teachers. Whether it is agricultural expertise or another specialty, Navajo women preserve Navajo practices and our way of life, passing on precious, traditional knowledge to future generations.

So, in many ways, Diné Asdzáán plant the necessary seeds for holistic community wellness.

Written by Raven McMullin

Let Us Know How We Are Doing

What has been most helpful to you and your community from this blog post? Do you have suggestions as to how we can improve this post or other content for next time? We greatly value your feedback as NLAP builds these resources and data contextualizations with Native Nations in mind.