Written by Aliyah Keuthan

Edited by Emma Scheerer

This blog is the second of two posts analyzing the challenges Native communities face accessing clean, sustainable water. Click here if you’d like to read part one.

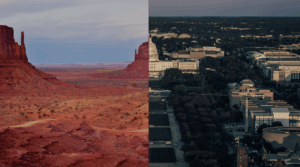

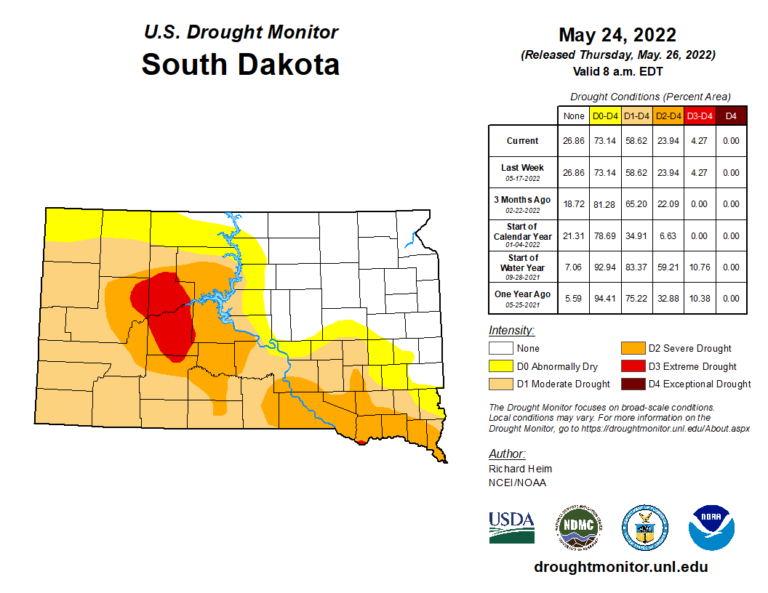

In South Dakota, west of the Missouri River, Lakota farmers have taken steps toward food sovereignty while grappling with limited funds, contaminated wells, and droughts. On the Pine Ridge reservation, semi-arid landscapes, floods, and drought create extreme climate conditions and challenges to food production. Combined with high unemployment rates and widespread poverty, this paints a bleak picture for Lakota communities struggling to achieve food sovereignty. On Pine Ridge, where extreme drought wreaked havoc in 2021, it threatened another growing season in 2022.

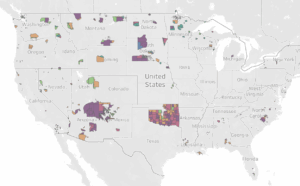

At the core of the food sovereignty movement in Native lands is the need for better water access for agriculture. The Native Lands Advocacy Project (NLAP) has documented a clear discrepancy between the irrigated cropland on Native lands being operated by non-Native farmers and the irrigated cropland of Native farmers. The data dashboard below, which depicts the percentage of irrigated acreage by race on all United States Indian reservations in 2017, calculates that 81.10% of irrigated land is operated by non-Natives, while 18.9% of irrigated land is farmed by Native farmers.

What factors are causing such a great disparity? And what solutions exist for the Native communities in South Dakota?

Limitations to Accessing Ground & Surface Water

Within the Mni Wiconi water system in South Dakota, people on Native lands face limited options for accessing the water necessary to fulfill their agricultural needs. Mni Wiconi water has certain restrictions on it; for example, small, one-acre farms are allowed to use Mni Wiconi water, while larger operations are not. If a farmer has rights to an existing well that has not been incorporated into the Mni Wiconi system, or can drill a new well into an uncontaminated aquifer, then he can irrigate larger areas–but these aren’t always affordable or accessible options.

On the Pine Ridge reservation, access to surface water is limited for several reasons. Federal dam projects (like the Angostura Reservoir) glean recreational revenue and provide irrigation off Native lands, diminishing water supplies downstream. Contamination of surface or groundwater from mining and commercial agricultural runoff leaves even fewer options for Native farmers. In the northernmost reaches of the Pine Ridge reservation, high levels of uranium and arsenic threaten groundwater and surface water supplies (Botzum et al., 2011; Swift Bird et al., 2020). In the mostly rural Mni Wiconi water system service area, roughly a third of the land is tribal land with vast panoramas of shrubby grassland and miles of desertified or semi-arid rocky terrain. In times of drought, irrigation is a necessity; Lakota farmers must be resilient and creative to keep their crops growing.

For Native farmers, the goals of agriculture go beyond profits. Food sovereignty, reduced dependence on external food sources, soil and water conservation, habitat restoration, and regeneration of viable soil are some of the goals being set by a new generation of Native farmers. These goals need water to succeed.

Well Access

While having the rights to an unincorporated well is one way to irrigate a larger area of land, drilling a new well is a potentially expensive venture. Professional well drillers charge by the foot, and well depths on the Rosebud reservation, for example, range from 44 to 275 feet according to a 2010 report (Long & Putnam, 2010).

According to Martin Indian Health Services (IHS) Office of Environmental Health and Engineering, which has provided new wells to hundreds of Native homesteads since the 1980s, enrolled tribal members do not need a permit to drill a well on tribal land. A professional well drilling service must be licensed by the state and must register the wells they drill with the state of South Dakota. Some wells on Native lands might be registered with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Before drilling, prior rights of way for accessing water can be determined through the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) in Pierre, South Dakota, or through the BIA. According to IHS, right-of-way conflicts in South Dakota are uncommon, but in the foreseeable future, disputes over water rights could become more frequent (personal communication, July, 2022).

Water Monitoring & Concerns About Sustainability

Legal requirements in the State of South Dakota limit individual water usage to 25,920 gallons per day, equalling 18 gallons per minute if pumped 24 hours per day. This cap is intended to discourage municipal, industrial, commercial, and institutional overuse, including excessive irrigation for commercial agriculture. A permit is required for any usage that exceeds these amounts. Like all of the state’s water, Mni Wiconi water is metered and monitored to curb overuse.

Federal funds for a system that benefits non-Natives could have been used to upgrade systems on Native lands, prioritizing Native families and communities (Energy and Water Development,1990, pp. 2886-88).

Willard Clifford stated that over one billion gallons of water are pumped through the Mni Wiconi system every year. On Pine Ridge, half of the water pumped through the Mni Wiconi system to Lakota households is from wells, which draw water from aquifers running beneath the reservations. An audit from 1999 (SDPB, 2021), estimated the population of the service area at 50,000, with 40,000 people on the three reservations. Clifford suggested that there may now be 10,000 more people on the Pine Ridge Reservation, suggesting population growth of about 50 percent over 20 years. A larger population indicates an increased need for water.

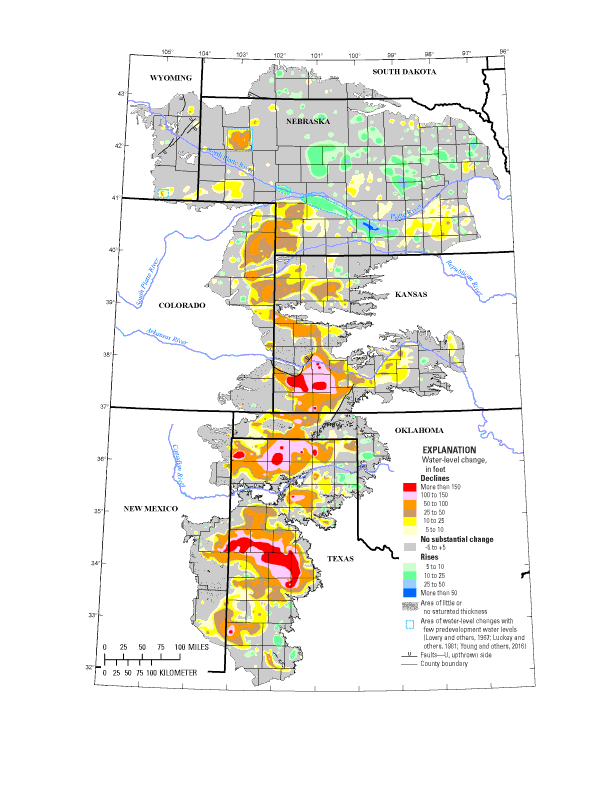

Sustainable access to sufficient water depends on conservation efforts, precipitation, and climate. To document water usage and sustainability, data concerning aquifers and the amount of time it takes for water to saturate water tables (known as recharge rate) is made available to the public.

A United States Geological Survey report from 2010, containing data from 1978-1998 and updated data from 2008, documents well depths, hydraulic conductivity, and recharge rates for the Ogallala and Arikaree aquifers on the Rosebud Sioux reservation, with data analyzed for normal precipitation as well as drought conditions (Long & Putnam, 2010). This report shows how groundwater resources depend upon recharge through precipitation. A drain on the water table at one point of the aquifer affects groundwater throughout the entire aquifer system.

The following Groundwater data dashboard, created by the Native Lands Advocacy Project, shows well levels as a means of detecting aquifer depletion on Native lands (2022).

Farming Techniques & Impacts on Water Sustainability

Because we are all dependent on one another to conserve water, it is vital to plan farming and industry around water conservation. Farmers operating on tribal lands and in South Dakota’s West River region must do two things: identify sustainable ways to get water to crops, horses, bison, and cattle; and utilize better methods of farming that conserve resources. Some farming techniques assist conservation efforts, while others hinder them.

The United States Census of Agriculture’s data for 2012 and 2017, shared by the South Dakota State University Extension Soils Field Specialist, Anthony Bly, exhibits changes in land use practices throughout the state of South Dakota (personal communication, August 26, 2020). According to the data, between 2012 and 2017, the following changes occurred in South Dakota’s land use:

Only a small percentage of farmers in South Dakota, including those who operate on tribal land, plant or use existing natural buffer zones to reduce erosion and runoff between cropland and waterways. Instead, more choose to maximize the amount of land used for crops, which allows runoff from chemical fertilizers and pesticides to freely pollute groundwater (Pfankuch, 2018). In drought conditions, chemicals in groundwater become more concentrated. The widespread use of chemical fertilizer and pesticides in commercial agriculture not only contaminates groundwater and soil at the site, but also spreads throughout the food chain. Agricultural runoff contributes to hazardous downstream waste where wells, crops, wild foods and medicines, wildlife, and domestic animals are exposed to contaminants through groundwater, soil, dried airborne particulates, and unhealthy vegetation.

While food sovereignty on Native lands depends on uncontaminated water for irrigation, it also depends on farmers to conserve the available water resources. This often requires farmers to adapt to agricultural practices that support water and soil conservation even as they compete for water resources.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge & Agriculture Legislation

Native values and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) about land and habitat make a difference in the farming methods Natives choose. Indigenous farming methods work in a synergistic manner with natural processes, focusing on respecting the land, conserving soil and water while conserving wildlife and habitat, and planning food production according to habitat management needs (Freeman, 1992; Houde, 2007). In contrast, conventional farming methods deplete topsoil, overextend water resources, and poison the land and waterways, causing catastrophic effects on the ecosystem.

Resistance to change in farming methods can indicate several possible deficiencies:

- perceived lack of effective regenerative soil management techniques,

- lack of knowledge about sequestering water runoff,

- improper use of cover crops and inadequate understanding of companion crops for adding and retaining nutrients to the soil and preventing pest infestation,

- inadequate use of organic fertilization methods such as composting, and

- lack of widespread education on the dangers of overusing commercial fertilizers and pesticides.

It takes time and care to build swales, measure green corridors, and plant buffer strips of hay and grass between crops and waterways. It’s possible that non-Native farmers don’t switch to more sustainable farming techniques because few monetary incentives exist for applying buffer strips along lakes and rivers. The percentage of cropland on the waterfront is minimal compared to overall cropland, but some farmers consider it barely worth the effort to change tractor routes (Pfankuch, 2018).

However, some non-Native farmers do support state regulations, citing fines as an incentive for promoting safe farming practices, rather than opting to wait for voluntary compliance, which has clearly not been enough to avert environmental degradation (Pfankuch, 2018). The state of Minnesota, for instance, passed laws in 2015 to regulate farming near water resources, and now has a 99% compliance rate with an increase of 20% in the first year.

Lawmakers in South Dakota have indicated that politics has an impact on conservation measures, such as when rural constituents push back at the polls against increased agricultural regulations. Others suggest that resistance to water and soil conservation among farmers is due to fragmented agricultural education and that public education has a great impact (Pfankuch, 2018).

Native Changemakers in South Dakota

In the midst of all these complex and interlocking factors, Native agriculture producers in South Dakota have been using sustainable methods and cultural knowledge to create change in their communities. We highlight a few of their stories here.

Pine Ridge: Medicine Root Gardening Program

On the Pine Ridge reservation, Lakota organic gardeners are eager to combine traditional techniques from multiple indigenous cultures with new strategies for farming in dry climates and extreme landscapes. They seek to embrace methods that conserve water as well as soil.

The Medicine Root Gardening Program, part of the Oyate Teca Project which is funded through the Newman’s Own Foundation, offers a nine-month course in organic gardening. The program teaches how to plan and grow organic produce, build a greenhouse, keep detailed garden records, and manage finances. Students earn seasonal income by selling surplus produce at the local farmer’s market. They learn how to preserve foods by canning or dehydrating them for use during the long Dakota winters. As of 2021, students had grown 20,000 pounds of produce (Running Strong, 2021).

Standing Rock: Mni Wiconi Health Center Community Garden

In the Northern part of the state, Sunshine Rose Claymore tackles food insecurity on the Standing Rock Reservation. Claymore is a board member of the Mni Wiconi Integrated Health Clinic and a graduate of Sitting Bull College with a Bachelor’s in Environmental Science. As a young Lakota mother, Claymore has a passion for environmental education and works tirelessly to restore degraded land and reverse the negative impacts of commercial farming and ranching.

NLAP spoke with Claymore about the community garden at the Mni Wiconi Health Center, where a drip irrigation system is incorporated into garden beds to grow Native trees, shrubs, berries, vegetables, and medicinals. Claymore is learning about alternative soil and water conservation techniques using hugelkultur, swales, berms, and mulching processes to counter dry land and increase access to fresh fruits and vegetables, while regenerating traditional habitat. The garden project is privately funded by four charitable groups and individuals.

Claymore explained some of the project’s challenges related to water access—all houses rely on municipal water, and individuals will share hoses in order for water to make it to their garden beds. But, water challenges aside, the garden has incorporated many sustainable methods. “I design to create microclimates,” she said, “[and] have been making an edible and Native windbreak. We planted buffalo berries, chokecherry, cottonwood, and willow, along with a lilac (which attracts pollinators) and sea buckthorn. I just plant the seeds and starts we are gifted to ensure they survive. I also brought raspberry cuttings from the Black Hills; the jam corner [has] raspberries, blueberries, and strawberries. We will expand it as things mature..” Claymore further shared that the cottonwood trees provide shade for their horses in addition to a natural windbreak.

She also discussed various techniques for composting, mulching, and other soil and water conservation methods she is planning for the future: “We hope to use local aged horse manure to create a future compost system. I would love to do more hugelkultur (a type of raised garden bed that is built with logs and plant matter). I’ve never seen or experienced Zuni waffle gardening here. We can make a test plot to see how it goes.” This traditional Zuni type of gardening creates a shape resembling a waffle with indentations in the soil for water catchment (Eric Jordan, personal communication, June 13, 2022).

Claymore also addressed the prevalence of non-Native conventional farmers on reservation land—the bulk of whom do not practice organic gardening. “There [are] whole communities,” she said, “who have health issues when they are spraying [chemical fertilizers and pesticides at] different times of the year. We have a water analysis lab where they test for organics, e coli, [and] minerals. We have various court cases involving water rights. The Army Corp owns all the shorelines where we used to get our food—in the abundant forests that were flooded in the 1960s and never restored.”

Global Partnership: Permacultures and Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Eric Jordan, a friend of Claymore, completed a Permaculture Design Course taught by Geoff Lawton in 2015. Jordan is an Asian American from California, where he lived for most of his life and then moved to Utah in 2021 to start The Thirsty Earth program, where he practices Zuni pueblo gardening techniques in combination with organic permaculture design.

Jordan recently embarked on a trip to South Africa, where he’d get to engage with NGOs in an organic permaculture project, discussing ways to blend indigenous African knowledge about Zai Holes (deep pits dug for water catchment) with Zuni Pueblo gardening techniques like waffle gardening and the use of ollas (partially buried clay or unglazed terracotta jugs) for holding water in the ground over long periods of time. Ollas are originally from Ancient China and Ancient Rome and have since been found in dryland regions across the world. Therefore, although used by tribes in the Southwest, ollas are not specifically a Southwestern tribal technique. The ollas use a process of osmosis to gradually water plants at the root and keep the soil moist below the surface.

Jordan then described how combining the method of waffle gardening and ollas with the African Zai Hole technique can benefit dryland agriculture. Jordan recounted that the raised ridges would funnel rainwater and overhead watering into the Zai pits where soil amendments like mulch, wood chips, newspaper, biochar, etc. increase its moisture retention. Jordan and others with the project discovered that the local Swazi permaculturists had independently come to the same conclusion and were already in the process of building this type of structure when they arrived in South Africa.

Jordan also demonstrated the drip/Olla mixed irrigation system that he helped to get operational in Eswatini, Africa, with excellent results three months later, using Permaculture, drylands farming techniques, and simple Ollas. Jordan’s group designed an easy-to-use system for the U.S. market, and can be found here.

Pine Ridge: Slim Buttes Agricultural Project

Since 1985, the Slim Buttes Agricultural Project (SBAP)—a partner organization with Running Strong for American Indian Youth—has been offering garden support on the Pine Ridge reservation. Seasoned gardener Tom Cook is the long term program director at SBAP. Slim Buttes organizers and volunteers offer support to food sovereignty projects on Pine Ridge through a network of gardeners helping and learning from each other, sharing seeds and seedlings, and working toward nutritional independence (Running Strong, SBAP, 2021).

In 2021, the program contributed 6,800 pepper seedlings, corn, potatoes, cucumbers, melons, and more to the community. The organization helps with tillage and offers a 10-week gardening course on the radio to reach more people. Children, elders, and their families experience meaningful connections to their land while being together in their garden. And at the end of the day, less people go to bed hungry.

While scaled-up commercial agriculture is generally unsupported by the Mni Wiconi water system, sustenance farming is rapidly expanding where community garden projects have sparked public interest. In-ground and raised-bed gardens, hoop houses, and other enclosed structures can be effectively irrigated with municipal water supplies, so in the future there may be more small gardens and less large-scale commercial farming, the end result of which is food sovereignty and enhanced sustainability.

Corrections & Updates Made (July 20, 2023):

- The author noticed that Eric Jordan’s full name was not fully spelled out in the reference list or the text. Eric Jordan’s full name has been added.

- It was written that Eric Jordan was from New Mexico, but Jordan is from California and currently lives in Utah. This was corrected in the post.

- Added further clarification of Jordan’s project in South Africa and clarity of the use of ollas.

- Added more clarity to the method of waffle gardening combined with the African Zai Hole technique.

References

Bly, A. (August 26, 2020). South Dakota Land Use Trends (2012-2017). South Dakota State University Extension. https://extension.sdstate.edu/south-dakota-land-use-trends-2012-2017#

Botzum, C. J., Ejnik, J. W., Converse, K., LaGarry, H. E., Bhattacharyya, P. (October 9, 2011). Uranium contamination in drinking water in the Pine Ridge Reservation. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, 43(5), 125. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312521024_CONFERENCE_PAPER_Uranium_contamination_in_drinking_water_in_the_Pine_Ridge_Reservation_southwestern_South_Dakota

Energy and water development appropriations for 1991: Hearings before a subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives, 101st Cong. 2 (1990) (testimony of Cecelia Fire Thunder). Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books/about/Energy_and_water_development_appropriati.html?id=k7CvXxweKqYC#v=snippet&q=mni%20wiconi%20water%20project&f=false

Freeman, M.M.R. (1992). The Nature and Utility of Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Northern Perspectives, 20(1), 9-12.

Houde, N. (December 20, 2007). The six faces of traditional ecological knowledge: Challenges and opportunities for Canadian co-management arrangements. Ecology and Society, 12(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-02270-120234

Long, A.J., Putnam, L.D. (2010). Simulated Groundwater Flow in the Ogallala and Arikaree Aquifers, Rosebud Indian Reservation Area, South Dakota—Revisions with Data Through Water Year 2008 and Simulations of Potential Future Scenarios. (Report No. 2010–5105). U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations. https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2010/5105/pdf/sir10-5105.pdf

Native Land Information System (2022). Tribal Lands and Aquifers. https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/native.lands.advocacy.project/viz/TribalLandsandAquifers_16579248373040/MapDash

Pfankuch, B. (September 5, 2018). Upgrading wastewater systems a $160 million task in South Dakota. South Dakota News Watch. https://www.sdnewswatch.org/stories/upgrading-wastewater-systems-a-160-million-task-in-s-d/

Pfankuch, B. (September 11, 2018). Should South Dakota farmers be forced to improve pollution control methods? South Dakota News Watch. https://www.sdnewswatch.org/stories/should-farmers-be-forced-to-improve-pollution-control-methods/

Running Strong for American Indian Youth (2021). Organic gardens and food. https://indianyouth.org/what-we-do/our-programs/organic-gardens-food/

Running Strong for American Indian Youth (2021). Slim Buttes Agricultural Project continues to “ground” Pine Ridge families to sources of life. https://indianyouth.org/slim-buttes-agricultural-project-continues-to-ground-pine-ridge-families-to-sources-of-life/

South Dakota Public Broadcasting (October 18, 2021). Repairs cause water restrictions for Mni Wiconi system. SDPB Radio. https://listen.sdpb.org/business-economics/2021-10-18/repairs-cause-water-restrictions-for-mni-wiconi-system

Yost, R. (July 15, 2022). 835,000 acres under irrigation permits in South Dakota. Retrieved from: https://www.keloland.com/keloland-com-original/water-in-steady-supply-for-irrigation-in-south-dakota/

Images:

Heim, Richard, and NCEI/NOAA (May 26, 2022). U.S. Drought Monitor – South Dakota [Online Map]. U.S. Drought Monitor. https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/data/png/20220524/20220524_sd_trd.png

Interviews:

Anthony Bly, personal communication, August 26, 2020.

Eric Jordan, personal communication, June 13, 2022.

Martin Indian Health Services Office of Environmental Health and Engineering, personal communication, July 2022.

Sunshine Rose Claymore, personal communication, 2022.